August 24. - And the loveliest day that ever came out of the sky.” Alas, our last at Cushendall. We were due at the Giant’s Causeway that night.

“You must go by the coast-road,” said our friend. “It is a little rougher, but much finer than the ordinary tourist-road. Malcolm declares that if you will send your luggage on by a separate car along the good road, he can easily manage this bad one—with Charlie.”

Good Malcolm’s zeal outran his discretion, but we assented, ignorantly as gratefully,' and started on an expedition which we shall always remember. It was one of the grandest —and roughest—roads we ever travelled in our lives.

Up to Cushendun and a mile or two beyond, it was a trifle hilly, but picturesque as that which winds along the Mediterranean Riviera. And no Ausonian sea could be bluer or calmer than that which lay beneath us. As empty too — scarcely a boat or sail dotting its solitary breast.

The land was everywhere well cultivated, though so close to the sea. Fields of oats waved in every bit of comparatively level ground, potatoes flourished in nooks of the cliffs; where, built in any possible corner, nestled tidy cottages. Bright-eyed children, quantities of fowls, and cows that seemed to have the talent of goats for climbing any- where, implied an industrious and thriving community.

“Ye’re right, ma’am,” said Malcolm pausing to converse and to breathe — he always led his horse uphill and downhill, as we began to notice. “They’re well off, most of them farmers. They pays their rint, and the masther’s always kind to thim.” Evidently the fierce battle between landlord and tenant was only a thing heard afar off on this fortunate coast.

Every minute it grew more beautiful — and more difficult. The girls were always getting out and in, and the car itself took an inclined plane now and again, which made “holding on” an anxious necessity. The tiny bits of level ground became so few that all who could use their legs did so. For Charlie his tottering legs were painful to behold, but his devoted Malcolm encouraged him and me.

“Don’t ye mind, ma’am. Charlie can do it. I'm holding his collar up. It was just about this place that a horse in a car with some gentlemen got choked with his collar, going uphill, and dropped down dead on the spot.”

At this cheerful information I tried to look as if there was nothing on my mind, but while I kept one eye on Tor Point, Fair Head, etc., etc., the other was fixed on Charlie.

My girls walked on and on, it must have been for over twelve miles, and declared this was the most splendid walk imaginable. The views changed every minute; the air was so bracing that they felt capable of anything. I know not whether we were glad or sorry to reach the bit of green high table land where, it had been kindly arranged, a little trap should meet us to take me down the very steep descent and up the ascent, at Merlough Bay.

It was not there. No sign of it, or any- thing. Suddenly Malcolm remembered a painful fact.

“It’s fair-day at Ballycastle, and there’ll not be a man in the place or a horse.”

This was serious, as we had trusted to getting a car here - our luggage, on another, having preceded us to Ballycastle.

“Never you mind, ma’am,” said Malcolm cheerily. “If it comes to the worst we'll give Charlie an hour or two’s rest, and I’ll take yez on to Ballycastle. I’ll get home by daylight to-morrow morning.”

And here he proposed that the young ladies should descend to Merlough Bay, while he “tuk care o’ the old lady”—which I must say he did most faithfully.

There was no road, but we jolted patiently across the moor, he leading Charlie, and 1 holding on as well as 1 could, till at last I begged to be allowed to walk, for a treat. At last we reached a farmhouse - whence, as Malcolm had foreseen, every available horse and man had vanished. He took possession of the empty stable, introducing me to the house, and to the mistress's kindly hospitality.

“You must go by the coast-road,” said our friend. “It is a little rougher, but much finer than the ordinary tourist-road. Malcolm declares that if you will send your luggage on by a separate car along the good road, he can easily manage this bad one—with Charlie.”

Good Malcolm’s zeal outran his discretion, but we assented, ignorantly as gratefully,' and started on an expedition which we shall always remember. It was one of the grandest —and roughest—roads we ever travelled in our lives.

Up to Cushendun and a mile or two beyond, it was a trifle hilly, but picturesque as that which winds along the Mediterranean Riviera. And no Ausonian sea could be bluer or calmer than that which lay beneath us. As empty too — scarcely a boat or sail dotting its solitary breast.

The land was everywhere well cultivated, though so close to the sea. Fields of oats waved in every bit of comparatively level ground, potatoes flourished in nooks of the cliffs; where, built in any possible corner, nestled tidy cottages. Bright-eyed children, quantities of fowls, and cows that seemed to have the talent of goats for climbing any- where, implied an industrious and thriving community.

“Ye’re right, ma’am,” said Malcolm pausing to converse and to breathe — he always led his horse uphill and downhill, as we began to notice. “They’re well off, most of them farmers. They pays their rint, and the masther’s always kind to thim.” Evidently the fierce battle between landlord and tenant was only a thing heard afar off on this fortunate coast.

Every minute it grew more beautiful — and more difficult. The girls were always getting out and in, and the car itself took an inclined plane now and again, which made “holding on” an anxious necessity. The tiny bits of level ground became so few that all who could use their legs did so. For Charlie his tottering legs were painful to behold, but his devoted Malcolm encouraged him and me.

“Don’t ye mind, ma’am. Charlie can do it. I'm holding his collar up. It was just about this place that a horse in a car with some gentlemen got choked with his collar, going uphill, and dropped down dead on the spot.”

At this cheerful information I tried to look as if there was nothing on my mind, but while I kept one eye on Tor Point, Fair Head, etc., etc., the other was fixed on Charlie.

My girls walked on and on, it must have been for over twelve miles, and declared this was the most splendid walk imaginable. The views changed every minute; the air was so bracing that they felt capable of anything. I know not whether we were glad or sorry to reach the bit of green high table land where, it had been kindly arranged, a little trap should meet us to take me down the very steep descent and up the ascent, at Merlough Bay.

It was not there. No sign of it, or any- thing. Suddenly Malcolm remembered a painful fact.

“It’s fair-day at Ballycastle, and there’ll not be a man in the place or a horse.”

This was serious, as we had trusted to getting a car here - our luggage, on another, having preceded us to Ballycastle.

“Never you mind, ma’am,” said Malcolm cheerily. “If it comes to the worst we'll give Charlie an hour or two’s rest, and I’ll take yez on to Ballycastle. I’ll get home by daylight to-morrow morning.”

And here he proposed that the young ladies should descend to Merlough Bay, while he “tuk care o’ the old lady”—which I must say he did most faithfully.

There was no road, but we jolted patiently across the moor, he leading Charlie, and 1 holding on as well as 1 could, till at last I begged to be allowed to walk, for a treat. At last we reached a farmhouse - whence, as Malcolm had foreseen, every available horse and man had vanished. He took possession of the empty stable, introducing me to the house, and to the mistress's kindly hospitality.

She was certainly “well off.” For the furniture in her parlour—a beautiful old clock, and presses of mahogany, almost black with age—would have delighted a collector. There were pictures of saints, and white images of the Virgin and Child. “We’re all Catholics in these parts,” Malcolm had said. And though the hens and their families ran about the door, and more than one shepherd's dog rose up angrily from before the turf fire, where he lay with the children, the place was exceedingly tidy, and the basin of hot bread and milk which the mistress gave me was truly delicious. I say “gave me,” for it was only by stealth that I was able to insert a small coin into the baby’s pudgy hand. She would have given me tea. or anything else she had, with the heartiest hospitality.

Not less kindness did the girls meet with. Malcolm and I, sitting like two crows on the hill top, and talking with that mixture of friendliness and entire respect peculiar to Irish servants, waited anxiously for them, and at last watched them slowly mount up from the bay— such a beautiful bay! “But ye couldn’t have done it, ye don’t know what it is,” said Malcolm consolingly. They had lost themselves, and got almost into despair, when they saw a farmhouse. The mistress took them into a most comfortable kitchen, where, in front of a large fire, upon a luxurious bed of straw, and surrounded by her eleven new-born babies, lay an enormous sow!

“The good woman seemed very proud of her interesting invalid. ‘She’s not a bit o' throuble, the crathur! Only she snores so, I can’t sleep o’ nights.’ It was the funniest sight you ever saw.”

And my two English girls laughed as if they never could stop laughing. They had been most hospitably treated, and offered hot potato-cakes — bread is rare in this region—but they were still able to attack the provision-basket- which had been kindly filled at Cushendall. And they spoke enthusiastically of the beauty of Merlough Bay, which, alas, I could not behold. And then Charlie, reappearing as fresh as ever, and Malcolm cheerily declaring the additional rive miles of his journey were "no throuble at all at all” we were ashamed to feel tired, and started off boldly for Ballycastle.

Not less kindness did the girls meet with. Malcolm and I, sitting like two crows on the hill top, and talking with that mixture of friendliness and entire respect peculiar to Irish servants, waited anxiously for them, and at last watched them slowly mount up from the bay— such a beautiful bay! “But ye couldn’t have done it, ye don’t know what it is,” said Malcolm consolingly. They had lost themselves, and got almost into despair, when they saw a farmhouse. The mistress took them into a most comfortable kitchen, where, in front of a large fire, upon a luxurious bed of straw, and surrounded by her eleven new-born babies, lay an enormous sow!

“The good woman seemed very proud of her interesting invalid. ‘She’s not a bit o' throuble, the crathur! Only she snores so, I can’t sleep o’ nights.’ It was the funniest sight you ever saw.”

And my two English girls laughed as if they never could stop laughing. They had been most hospitably treated, and offered hot potato-cakes — bread is rare in this region—but they were still able to attack the provision-basket- which had been kindly filled at Cushendall. And they spoke enthusiastically of the beauty of Merlough Bay, which, alas, I could not behold. And then Charlie, reappearing as fresh as ever, and Malcolm cheerily declaring the additional rive miles of his journey were "no throuble at all at all” we were ashamed to feel tired, and started off boldly for Ballycastle.

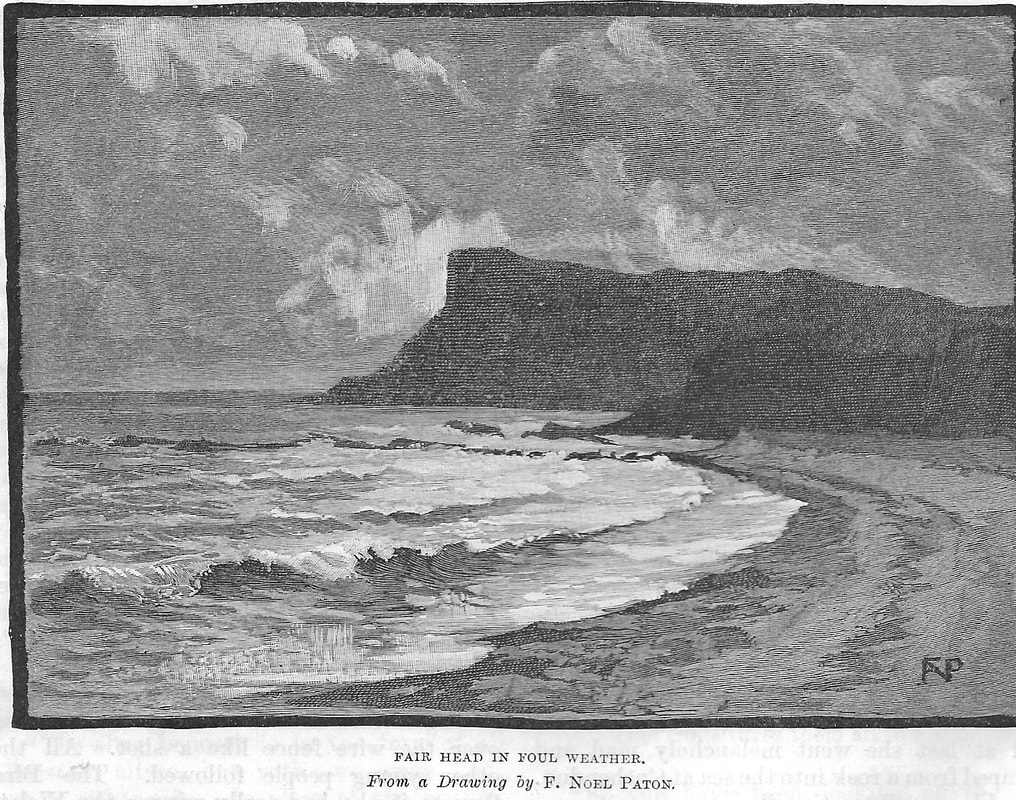

“Fair Head in foul weather,” as our artist saw it and has depicted it, we did not see, for it followed us, or rather we it, for many a mile, standing out clear against the bluest of skies, with the calmest of seas below. We longed to have been able to do—what all tourists should do - take a boat at Merlough Bay, and row under this grand headland, with its basaltic pillars, three hundred feet high, its other broken pillars lying on the beach below, and above, the Grey Man’s Path —another pillar which, in its fall ages and ages ago, has lodged across a chasm in the rock, and up which on stormy nights a grey man is said to stalk. On the top of Fair Head are three fresh-water lakes, in one of which may still be traced the remains of an old lake dwelling, and not far off a cromlech, once used for badger-baiting. “The fine old Irish gentleman” of yesterday -perhaps even to-day—was more of a sportsman than an archaeologist. Else Bonamargy Abbey, which we passed a short distance from the road (it really was a road, level and good at last !), would never have had its ancient ruins disfigured by a hideous slate-roofed, modern excrescence, and its tombs—it was for four centuries the burial place of the McDonnells—broken, defaced, and destroyed. Our artist had been deeply interested in it and has sketched it con amore.

Ballycastle, which we were now approaching, was a hundred years since a flourishing town. Its valuable coalfields, extending along the coast to Merlough Bay, belonged to a Colonel Boyd, whose influence brought about the erection of a fine harbour. But he died, and all fell into decay. The harbour became a ruin, the docks a green field. Speculators worked the coalfields by fits and starts, but always at a loss, and Bally castle was fast sinking into oblivion, when the railway between Belfast and Portrush stopped at it— and saved it.

Now, to all appearance, it is a thriving place. As we passed through its suburbs we noticed several good, nay, handsome houses. Its market-place was crammed with people. In addition to the groups of men and beasts that we had met coming from the fair, booths, with dancing and theatrical artistes outside, attracted each its little crowd, and in the midst I saw more than one woman trying to soothe or lead home a drunken husband whom nobody minded, or only laughed at.

Such sights from the hotel windows did not encourage us to stay the night there, nor did a little episode in the coffee-room— which we shared with a gentleman and his wife. She lay on the sofa and looked as if she had been crying. Suddenly the window was thrown up from outside.

“Will your honour have the carriage round at six?”

“At six,” answered ‘his honour,’ rather grumpily.

“And will ye have the bull tied behind it?”

“Certainly, certainly.” At which we did not wonder that the lady on the sofa looked cross as well as tired. But it was evidently the custom of the country.

Ballycastle, which we were now approaching, was a hundred years since a flourishing town. Its valuable coalfields, extending along the coast to Merlough Bay, belonged to a Colonel Boyd, whose influence brought about the erection of a fine harbour. But he died, and all fell into decay. The harbour became a ruin, the docks a green field. Speculators worked the coalfields by fits and starts, but always at a loss, and Bally castle was fast sinking into oblivion, when the railway between Belfast and Portrush stopped at it— and saved it.

Now, to all appearance, it is a thriving place. As we passed through its suburbs we noticed several good, nay, handsome houses. Its market-place was crammed with people. In addition to the groups of men and beasts that we had met coming from the fair, booths, with dancing and theatrical artistes outside, attracted each its little crowd, and in the midst I saw more than one woman trying to soothe or lead home a drunken husband whom nobody minded, or only laughed at.

Such sights from the hotel windows did not encourage us to stay the night there, nor did a little episode in the coffee-room— which we shared with a gentleman and his wife. She lay on the sofa and looked as if she had been crying. Suddenly the window was thrown up from outside.

“Will your honour have the carriage round at six?”

“At six,” answered ‘his honour,’ rather grumpily.

“And will ye have the bull tied behind it?”

“Certainly, certainly.” At which we did not wonder that the lady on the sofa looked cross as well as tired. But it was evidently the custom of the country.

We thought, in case the bull might be going our way, we had better drive off at once ; so we bade a cordial and grateful adieu to Malcolm, who persisted that he should be home “long before daylight,” and that Charlie would not be a bit the worse—and departed, in a waggonette this time, where if we dropped asleep—not unlikely !—we should at least lie safe from falling off.

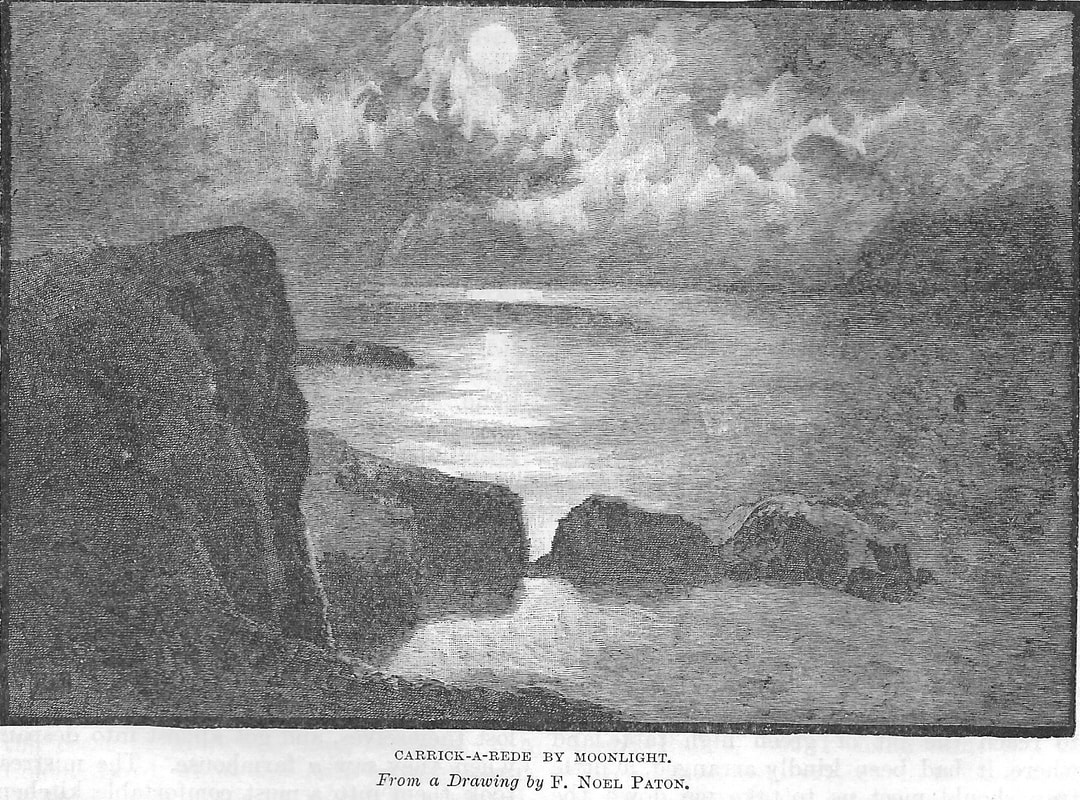

The evening shadows and a slight drizzle —made us less eager after scenery, yet when our driver said, “Carrick-a-rede, ladies,” my girls roused themselves and insisted, under the guidance of a small, a very small, boy, who was captured hard by, on going to see it.. In their absence our driver politely began to entertain me.

“I druv a young gentleman to Carrick-a-rede the other day, who made a pictur of it. He was a fine young gentleman and well up to things. he seemed to think we were all Home Rulers, but I tould him no, the Queen has as loyal subjects in Ireland as she has anywhere, if she only knew it. There’s a gentleman named Parnell, as makes a great talk, but half of us don't know him, or care for him. And there’s Mr. So and So, and So and So— ”

Here he entered into a long political tirade, which I will not repeat, and, indeed, can scarcely remember; except that he wound up by wishing it would please Providence to take a certain old man—who had been, as I insisted, a good and great man in his day—to another and a better world. I only name this to show how fierce on both sides are the political parties who tear Ireland to pieces between them as fierce as those semi-savages who fought with Shane O’Neill and with Sorley Boy M’Donnell along these very shores.

Dunanynie Castle, where this renowned Sorley Boy was born and died—quietly in his bed, for a wonder! — is the merest ruin. But Dunseverick Castle, which now loomed large in the twilight, and distracted my girls’ attention from the wonders of Carrick-a-rede (of which more by and by)—is a much older fortress; indeed, it is said to have been built by a Milesian from Asia Minor in the year of the world 3668! Certainly it is mentioned in the Annals of the Four Masters, as having been visited and blessed by St. Patrick.

We longed to stop and investigate it, standing on its detached island-rock, absolutely impregnable from the sea, and only connected with the mainland by a natural portcullis—a strip of green a few yards wide. But the gathering darkness would have made such an attempt very unsafe. And we had still before us miles of gloomy, unknown road ere we could reach the Giant’s Causeway.

What it was like, or what sort of refuge we should find there for our weary bones, was equally unknown to us, but we were too worn out to speculate. I rather think for the last mile or two we sank into total silence; the road seemed interminable and we felt as if it was years since we had left the happy shelter of Cushendall.

But every journey comes to an end some time; and never did weary wayfarers hail a pleasanter sight than the gleam of light from the opening door, or enjoy a more welcome tea, and still more welcome bed, than we did when we arrived at last at the Giant’s Causeway.

The evening shadows and a slight drizzle —made us less eager after scenery, yet when our driver said, “Carrick-a-rede, ladies,” my girls roused themselves and insisted, under the guidance of a small, a very small, boy, who was captured hard by, on going to see it.. In their absence our driver politely began to entertain me.

“I druv a young gentleman to Carrick-a-rede the other day, who made a pictur of it. He was a fine young gentleman and well up to things. he seemed to think we were all Home Rulers, but I tould him no, the Queen has as loyal subjects in Ireland as she has anywhere, if she only knew it. There’s a gentleman named Parnell, as makes a great talk, but half of us don't know him, or care for him. And there’s Mr. So and So, and So and So— ”

Here he entered into a long political tirade, which I will not repeat, and, indeed, can scarcely remember; except that he wound up by wishing it would please Providence to take a certain old man—who had been, as I insisted, a good and great man in his day—to another and a better world. I only name this to show how fierce on both sides are the political parties who tear Ireland to pieces between them as fierce as those semi-savages who fought with Shane O’Neill and with Sorley Boy M’Donnell along these very shores.

Dunanynie Castle, where this renowned Sorley Boy was born and died—quietly in his bed, for a wonder! — is the merest ruin. But Dunseverick Castle, which now loomed large in the twilight, and distracted my girls’ attention from the wonders of Carrick-a-rede (of which more by and by)—is a much older fortress; indeed, it is said to have been built by a Milesian from Asia Minor in the year of the world 3668! Certainly it is mentioned in the Annals of the Four Masters, as having been visited and blessed by St. Patrick.

We longed to stop and investigate it, standing on its detached island-rock, absolutely impregnable from the sea, and only connected with the mainland by a natural portcullis—a strip of green a few yards wide. But the gathering darkness would have made such an attempt very unsafe. And we had still before us miles of gloomy, unknown road ere we could reach the Giant’s Causeway.

What it was like, or what sort of refuge we should find there for our weary bones, was equally unknown to us, but we were too worn out to speculate. I rather think for the last mile or two we sank into total silence; the road seemed interminable and we felt as if it was years since we had left the happy shelter of Cushendall.

But every journey comes to an end some time; and never did weary wayfarers hail a pleasanter sight than the gleam of light from the opening door, or enjoy a more welcome tea, and still more welcome bed, than we did when we arrived at last at the Giant’s Causeway.