THE following is an account of an island little known to tourists, but possessing much to interest the curious traveller, and affording ample scope for the exercise of their several talents to the botanist, the geologist, the painter, the ornithologist, and the general lover of natural history.

SITUATION AND DIFFICULTY OF ACCESS.

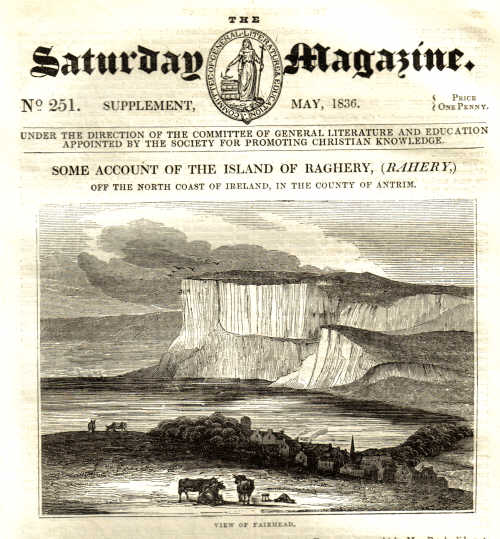

THE Island of Raghery, Rathlin, or Rachlin, (for it is called by all these names indiscriminately, both by their neighbours on the mainland and by the natives,) is situated about five miles to the north of Ballycastle, a small town in the north-east corner of the county of Antrim, which was raised into some note in the early part of the last century by the fostering care of a spirited individual, Mr. Boyd, who spared no pains to improve his native place, and convert it from an insignificant fishing-village, into a flourishing manufacturing-town. Having accidentally discovered the shaft of an old coal-mine upon his estate, at the foot of the promontory of Fairhead, he proceeded to work it, and built a large glass-house on the sea-shore, as near as he conveniently could to the coal-pits. The numerous fine flints produced in the neighbourhood, as well as the sand in Ballycastle Bay, afforded him means of carrying on his operations at small expense. The demand for coals, and the need of hands to pick and sort the flints, to sift the sand, and to perform the other operations of the glass-house, caused a town to spring up around him. And that the good man might not have his undertaking incomplete, he built and endowed a chapel of ease for the growing town population. From causes, which Mr. Boyd did not anticipate, the prosperity of Ballycastle as a place of trade, has not continued. The collieries are almost at a stand; but the chapel remains for the accommodation of the inhabitants, being the building, the spire of which is seen in the accompanying sketch; and the glasshouse still resists the heavy blasts from the north, and the waves which often rise mountains high at the foot of the quay, which was built to protect the rising town from the inroads of the Northern Ocean.

This quay is the starting-place for those who would go to the island of Raghery, which lies due north of Ballycastle, stretching from the south-east or Ushet point, to the Bull Rocks at the south-western point of the island, about six miles. It is easily approached in fine weather by a smooth sandy shore towards the south, where the land recedes so as to take a crescent shape, thus forming a fine sheltered bay called Church Bay. Two other landing-places are used to the eastward, the Ushet and the Doon Points.

But every part is perfectly inaccessible in stormy weather, so that the inhabitants are not unfrequently for two or three weeks prisoners in the island, and perfectly unconscious of the affairs of their mainland neighbours, at the Winter season, or about the times of the equinoctial gales. But as there is no situation free from disagreeable circumstances, so is none without its advantages; and this stormy seclusion once saved the island from the miseries of civil war. In the unfortunate year 1798, when rebellion had broken out in every part of Ireland, and the inhabitants of the island of Raghery, generally peaceful and inoffensive as they are, were sworn to assist their mistaken neighbours on the mainland, one of those tremendous gales set in: the weather was not only stormy, but the whole coast was so enveloped in fog, that no signals could be discerned; nor could any boat either leave or approach the Isle of Raghery, till the misguided leaders of the rebellion in Ireland were subdued, and peace and tranquillity was re-established.

FIRST VISIT TO THE ISLAND.

IT was near the approach of the autumnal equinox, a few years ago, that we first visited the island of Raghery ; and we were ensured six hours of calm weather if we would immediately embark and be prepared to return within the time specified.

The sea was smooth as a mirror, as our light boat skimmed its surface: from the state of the tide, however we were unable to steer right across the channel from Ballycastle to Church Bay, the usual landing-place in Raghery; but kept along the Antrim coast towards the east, until we came close under the huge promontory of Benmore, or Fairhead, which is no-where seen to so great advantage as from the sea, whence it rises first in an angle of about forty-five degrees, and then in a perpendicular direction to the summit, where the rock is clothed with a beautiful carpeting of turf, moss, and wild-flowers, pleasing to the foot of the traveller, as the magnificent scenery around is most delightful to his eye. Fairhead is the first regular formation of basalt, which occurs in mass, and the existence of which is traced from the Cave Hill, near Belfast, and detected at intervals from thence to the eastward, on the chain of mountains which skirts the north side of the Lough of Belfast, till the headland takes a sudden turn to the north, near the rocks called the Gobbins. Again the basalt is found at various distances from the surface, all along the eastern coast of Antrim; but it assumes no regular form till Fairhead appears as another boundary to its progress eastward, being pushed forward, if I may so say, in primitive majesty, and overlooking westward the whole basaltic range, which commences at that headland, and occupying the northern coast of Ireland, is bounded only by the mountains of Donegall. Fairhead itself is a very noble object, as will appear to the reader from the sketch at the head of this article, taken from the Rectory-house of Ramoan, in which parish Ballycastle is situated; the town being in the foreground of the sketch, and the Mull of Cantire in the distance.

Many of the columnar stones which form this magnificent promontory, are said to be four hundred feet high; for the most part irregularly quadrangular, and continuous throughout their length, instead of being broken into joints, as is the case with those at the Giants’ Causeway, about ten miles to the west of Ballycastle, and at other detached masses observed more westward, and in the interior of the country. As this noble headland, however, is not immediately connected with my subject, except as it formed a feature on our passage to Raghery, and has been selected for the embellishment of this article, I will not detain the reader with more particulars, but refer him for further satisfaction to Hamilton’s Letters on the Coast of Antrim, and Conybeare’s Geological Account of the same; and proceed at once to the proper subject of this narrative.

I mentioned that, in consequence of the state of the tide, we were compelled, on our first visit to Raghery, to direct our course from Ballycastle to Fairhead, whence we were obliged to land at one of the eastern points, namely, the Ushet Point, and walk a distance of about two miles to the most habitable part of the island, where the proprietor’s house, the coast-guard station, and a few scattered fishermen’s cabins with the little church in the distance, form a sort of village-scene, highly picturesque and pleasing.

The walk was one of uncommon beauty and variety: rocks of every description of materials seemed in some places thrown together or broken into fragments in the greatest confusion, others looking as if chiselled and piled by the most skilful workmen, sometimes the hills on each side the narrow valley through which we passed, approached, or receded, now clothed with the most brilliant verdure, and now rugged and bare, scattering their crumbling ruins in the low ground, with every rough breeze or descending shower. About midway between Ushet and Church Bay, is a lovely little lake where the coot and the moorhen were rearing their still downy broods, and disporting themselves on its glassy surface ; a high red sand-bank close to the road, on one side of our path, was peopled with multitudes of the martin tribe who seemed to nestle and enjoy the plentiful supply of food engendered by this sheltered piece of water.

Our stay necessarily being very short, on reaching Church Bay, we could only run to the church and take some hasty refreshment at the proprietor’s house, when it was time to embark again. “ Be quick, be quick,” said the boatmen, “ we have no time to lose,” as I lingered on the shore to look around me, “ we shall but just save the tide.” Away then we went with the same soft air and glassy sea, and the view of the island we had left, and of Ireland as we approached it, was one of much grandeur and beauty. Fair Head, that magnificent promontory of Basalt, was seen in its full proportions, but softened by the slight haze of distance and the declining sun. Then, as we came nearer the coast of Ireland, the lights and shades were thrown across the indurated chalk cliffs of Kenbaan, standing forward in glittering whiteness to the westward, and further were stretching to the verge of the horizon the abrupt headlands of the Giants’ Causeway, the view being terminated in the distance by the island of Innishowen and the mountains of Donegal, nor were the Scottish islands to the east wanting, to finish the picture. As we neared the land, a small cloud came sweeping across the sky. We saw and admired its effects on the surrounding scenery. but before we had time to enjoy much of its beauties the sailors plied their oars, lowered the sails, and, in short, evinced that sort of restlessness which makes landsmen feel a little anxious to know what the careless-looking beings of a few moments ago can see to be so disturbed about. We flew over the waves, for waves we had now under us, till we got within the shelter of Kenbaan Head, beneath the high grounds of Clare, when almost as suddenly the men relaxed from their labours, and we were then in a calm, but not a glassy sea, for the short ripple showed that all was not as peaceful as it had been. We, however, landed at Ballycastle in safety, but before we were well off the landing-place, the waves dashed up and broke in white foam all around us. If we had not taken the precise time between tide and tide, we might have been detained several days before we could have reached the mainland; indeed, I was told that it was nearly three weeks before a boat could leave the island of Raghery after that evening, for the gale set in and raged with unabated fury for that time. I have mentioned our adventure to show, that, however this island is worth visiting, it requires more than common prudence and foresight, and withal, an entire dependence on the island boatmen, to choose your time, or you may be detained longer than it may be convenient to you, particularly as at present there is no house of public entertainment for the accommodation of travellers, except for the least fastidious pedestrian.

VISIT REPEATED IN 1835.—INHABITANTS.

LAST year, in the month of August, I had again the good fortune to be one of a party visiting Raghery ; when, as the kind proprietor and his family were at home, we had every facility of seeing more of the interior than we had on our former trip. Mr. G. had his boat ready for us, and himself was its steersman. The day on land was fine and promising, but the sea, though looking only pleasantly waved near Ballycastle, whence we again took boat, was considerably agitated when we got out into the channel free from the influence of the sheltering headlands of the bay, and exposed to the full force of the contending currents, as they swept round the many bold promontories of Ireland, meeting those which boil round the rocky capes of Raghery. However, after a rough but safe passage of two hours, we landed on the island, and were most hospitably received by the family of the proprietor.

Mr. G. combines the interesting characters of owner of the soil, rector of the parish, and the common master and friend of every creature within its bounds. His account of their character and conduct was very creditable to their general freedom from vice, and their peaceable and orderly behaviour: corresponding with the statement of Dr. Hamilton, who, in his “ Letters on the north coast of Antrim,” written about 1790, speaks of the inoffensive character of the inhabitants of Raghery, as well as the affectionate relative understanding between the master and his people. “ The tedious processes of civil law,” says Dr. H., are little known in Raghery ; and, indeed, the affection which the inhabitants bear to their landlord, whom they always speak of by the endearing name of master, together with their own simplicity of manners, renders the interference of the civil magistrate very unnecessary. The seizure of a cow or a horse for a few days, to bring the defaulter to a sense of his duty, or a copious draught of salt water from the surrounding ocean, in criminal cases, forms the greater part of the punishment on the island. If the offender be wicked beyond hope, banishment to Ireland is the last expedient resorted to, and soon frees the community from its pestilential member.”

Mr. G assured us that for the last forty years no heinous crime, deserving severe punishment, had been committed on the island : and no islander has ever seen even the outside walls of the county gaol.

It is indeed rather esteemed a hardship by the islanders, that they are required to contribute in this respect to the support of a building with which they have no concern, satisfied as they are to discharge the other legal demands to which they are liable. In answer to a question, whether any objections were made by them to the payment of tithes, the answer was. “ they object to no payment of any kind, except the county cess: but they do think it hard to pay a charge of 200 l., which is levied on the island for making roads in the County of Antrim, which they never travel, and for building and repairing the county-gaol, of which they have never seen even the outside walls.”

Agriculture is the principal employment of these islanders, but its operations did not appear to be carried on with judgment and skill. Much of the standing corn, particularly on the eastern side of the island, was intermixed and choked with weeds; the cow-rattle, the ox-eyed daisy, the rag-weed, and the broad-leaved sorrel, were conspicuous features in the furrows, and even made their appearance high up the ridges amongst the barley and oats. The holdings of the several tenants are very small: the appearance of the farmers and of the inhabitants in general is much the same as that of the people on the main land, and their habitations seem to possess the like scanty stock of the conveniences and comforts of life; but they have less numerous and active incentives to vice and misery, inasmuch as they have fewer whisky-shops, and are under the constant superintendence of their master’s eye, to check them by marks of displeasure, when they are known to have been guilty of any excess, and to encourage them with approbation whilst they continue to do well.

Inducements to greater industry have been lately given to the islanders, by means of the steam-packets which are continually passing on thoir way between Scotland and Ireland, and afford them opportunities, which formerly they did not enjoy, of disposing of the produce of their land and sea. They now catch large quantities of fish, for which they have a ready sale at their own doors, particularly lobsters and crabs. The collecting also of the different sorts of sea-weed employs a number of the women and children : some of this is burnt into kelp, and readily disposed of to the bleachers, and used not only in the Scotch and Irish linen-manufactories, but also in the whitening of calicoes and paper. The encouragement given of late years to the making of beds and mattresses from one of the Ulvae, commonly known as the riband-weed, is also likely to be an incitement to their industry, and to contribute to their domestick comforts by its produce.

The collecting of the sea-weed is the occasion of a very cheerful and entertaining scene. The people go down to the shore in troops, after the heavy gales, acting upon the ocean, have washed up the weeds from the bottom of the sea, or from some softer ground than the rocky shores of Raghery; and from the merry shouts and peals of laughter which I heard as I wandered near a party employed in the collection, it seems to be a great source of amusement to intercept the prey before the retiring wave shall have buried it again in the deep, or wafted it far away to other more fortunate lands. The weeds, being thus secured, are placed on sticks of every description, from the broom-handle to the roughest raft-wood, and so carried to the rocks which lie out of the reach of the next tide. They are there suspended, for the purpose of draining from them all the sea-moisture ; and the turning and exposing of them to the sun and wind requires constant attention, and affords employment to this class of the population.

HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE ISLAND.

OF the early history of Raghery, I am unable to offer much information: but in the ancient historical records of Ireland and Scotland, a few scattered notices occur, of this little spot, which have been collected by Sir James Ware, in his Antiquities of Ireland, and exhibited more recently by Dr. Hamilton, in his Letters on the Coast of Antrim, and by Archdale in his Wonasticon Hibernicum. For the present purpose, it may be sufficient to state the following particulars, the authorities for which may be found in the works just mentioned.

The island has been known by a great variety of names. By Pliny, who seems to have been the first to notice it, it is called Ricnea; by Ptolemy, in the time of the Antonines, Ricina; by Antoninus, Riduna. By the Irish historians, it is called at different times Recarn, and Recrain, and Rechran; Raghlina, and Raghlin; Raclinda; Raghery, and Raghry, by which last name Harris, in his edition of Ware’s Antiquities, says it was known in his day, namely, 1745; and as Archdale reports its appellation by the Irish antiquaries, Rochrinne, “ from the multitude of trees with which it abounded in ancient times.” The latter part of this word, “ Chrinne,” or something similar to it, I am told is the Irish word for tree. As to the etymological sense of the name here given to the island, I am incompetent to form an opinion ; but it is certainly remarkable how generally prevalent in Ireland is the persuasion of trees having formerly abounded in districts which are now altogether bare ; though the bogs bear ample testimony to the probability of the fact, from the frequent occurrence of large masses of timber, whose various species may be easily recognised; as the oak, the pine, the alder, and the yew, of former ages. Raghery is at present anything but “ abundant in trees.”

Except those in the immediate neighbourhood of Mr. G. s house, there is scarcely a tree to be found in the whole island, as large as a common-sized gooseberry-bush. There, a few stunted elders, enclosing some very small sycamores, which have been planted near thirty years, scarcely deserve the name of a copse. But as they do, nevertheless, form a screen to protect the garden from the south-east and south-west winds, they must not be passed entirely without notice ; though in any place but Raghery, or places similarly circumstanced, for instance, much of the sea-coast of Ireland, one would be hardly sensible of their existence.

A church is related to have been founded in this island by St. Columba, in the year of our Lord 541 : and to have been repaired in or about 630, by Segenius, abbot of Ja, or Hy, in Iona, who by some persons is said to have been its founder. But it was destroyed about 794, by the Danes, “ who then first infested the Irish and Scotch coasts, and particularly the Isle of Recran.” They laid waste the island with fire and sword, and in the general devastation the shrines and holy altars perished; so that, as a contemporary author writes, this and other islands about Ireland “had not so much as an anchorite on them.” To these invasions of the Danes are attributed the several remains of mounds or forts which are still found in Raghery, though scarcely more than a foundation of them can be traced at present. The accounts given by the inhabitants concerning these remains are so full of the marvellous, as to afford no satisfactory information: but the resemblance which they bear to other similar remnants of antiquity, which in several parts of Ireland are called “ Danish forts,” give probability to the opinion that these also are of Danish origin.

Without pretending to investigate the circumstances of Raghery during the succeeding ages, till after the invasion of Ireland by the English in the reign of King Henry the Second, I may observe, according to Ware, “ King John of England gave this island among other things to Alane de Galway, as we find in the records.” This must have been early in the thirteenth century, as John reigned from 1199 to 1216, having, however, been “Lord of Ireland” some years sooner. The next occurrence, with which it is connected, will give it a more interesting character with the general reader: for in 1306 it became a place of refuge to Robert Bruce, who is related by Buchanan, as cited by Dr. Hamilton, page 29, to have “ fled with a single companion to the Isle of Raghery, which is classed by Buchanan amongst the AEbude or Western Islands of Scotland, under the name of Raclinda.” Of this event, traditionary evidence is preserved in the island, substantiated by the ruins of a castle which afforded shelter and protection to the Scotch king, and is still known by the name of Bruce’s Castle. Sir Walter Scott in his Lord of the Isles, alludes to the event in the following lines :--

Suspicious doubt and lordly scorn

Lour’d in the haughty front of Lorn.

From underneath his brows of pride

The strange guests he sternly eyed,

And whispered closely what the ear

Of Argentine alone might hear:

Then question’d high and brief,

If in their voyage aught they knew

Of the rebellious Scottish crew,

Who to Rath-Erin’s shelter drew,

With Carrick’s outlaw’d chief?

And if, their Winter’s exile o’er,

They harbour’d still by Ulster’s shore,

Or launch’d their galleys on the main,

To vex their native land again ?

And he adds in a note, that “ the islanders at first fled from their new and armed guests; but upon some explanation submitted themselves to Bruce’s sovereignty. He resided among them until the approach of Spring, when he again returned to Scotland.”

If the fortress, the ruins of which now hear the name of Bruce, afforded him a refuge during his residence in the island, it must he of earlier date than 1306, the period of his sojourn there : for that this castle could not have been built by Bruce, seems evident from the facts of his having come to the island in the Winter, and leaving it in the following Spring. Concerning the builder, however, or the date, of the ruined fortress, not even a traditionary account now remains.

In 1551, the fifth year of king Edward the Sixth, a passing notice is made of the island, in connexion with the general disturbances of the North of Ireland.

Sir James Ware informs us, in his Annals (p. 114,) “ that Sir James Crofts, the Viceroy, marched against the rebelling Irish in Ulster, and their abettors, the Scotch islanders. From thence, to wit, from the town of Knockfergus, he sent some of his forces to the island of Raghlina by Ptolomy called Ricina, where they had very ill success, not a few of them being slain by the Scots, and one of his ships suffering wrack.”

In 1558, the sixth of Queen Mary, “ the Earl of Sussex, Lord-Lieutenant, returned out of England into Dublin with 500 armed soldiers, as well for the suppressing of rebels, as also of the robberies and pyracies of the islanders; in September,” as Ware goes on to say, (p. 145,) “ taking ship at Dalk, he sailed unto the Isle of Raghlin against the Scots. In that while that my Lord-Lieutenant was a landing, one of his vessels, by force of the tempest, was split near the shore, whereby some of the citizens of Dublin were swallowed up by the waves and perished. However, the Lord-Lieutenant himself, with the rest. landed, and having killed those that resisted, they wasted the island, and leading his forces from thence to Cantire, there made a vast destruction.”

In 1580, according to a MS. cited by Dr. Hamilton, (p. 124,) in consequence of a plot laid by the Irish M’Quillans, the proprietors of the neighbouring mainland, against a party of the Scotch M’Donalds, “ the Highlanders fled in the night-time, and escaped to the Island of Raghery, which not being inhabited at the time, they were forced to feed on colts’ flesh for want of other provisions.”

The war between the M’Donalds and the M’Quillans which ensued, and continued through the rest of the century, was terminated on their joint appeal to King James the First, soon after his succession to the English throne. Four great baronies were, thereupon, made over by patent to the M’Donalds; and the Isle of Raghlin appears from that time to have continued in undisturbed possession of that family, until it was transferred by sale, early in the last century, from the Earl of Antrim to the ancestor of Mr. Gage, the present proprietor.

To as late a period as the commencement of the last century, the island, though it contained about 500 inhabitants, had no resident clergyman, but was annexed to the parish of Ballintoy, on the mainland of the county of Antrim, about five miles to the west of Ballycastle. Dr.Francis Hutchinson, who succeeded to the Bishoprick ofDown and Connor in 1720, exerted himself to provide for the spiritual wants of these poor people: and in consequence the Rev. Dr. Archibald Stewart, Rector of Ballintoy, gave up the small tithes of Raghery, and the Trustees and Governors of Queen Anne’s Bounty, out of the First Fruits, bought the great tithes, as a provision for the future minister; and by means of subscriptions from the gentlemen and clergy in the neighbourhood, a new church was built on the ruins of an old one, the island being erected into a new parish. This event was commemorated by an inscription, painted on a board, and placed on the communion-table of the church. “ in honorem Dei Omnipotentis, Haec Ecclesia Sti. Thomse reaedificata fuit auspiciis, et ornata sumptibus, Reverendissimi in Christo Patris, Thomae, totius Hiberniae Primatis et Metropolitani, A.D. 1723.” (To the honour of Almighty God, this church of St. Thomas was rebuilt under the auspices, and adorned at the expense, of the most reverend Father in Christ, Thomas, Primate of all Ireland, and Metropolitan, in the year of our Lord 1723.) “My house shall be called an house of prayer for all people.” The Bishop also procured the Church Catechism to be translated into Irish and printed it in columns of English and Irish, calling it the Raghlin Catechism, built a parsonage house, and a good school for teaching English, and purchased, by contributions’ from himself and others, a collection of books for the incumbent. The church, which forms a conspicuous object in the prospect from the opposite coast, and on the intermediate passage, stands upon the edge of the sea, and gives the name of Church Bay to the curved shore on the southern side of the island.

From the above period the island has been under the pastoral care of its own parochial incumbent, so that the value of Bishop Hutchinson’s exertions is incalculable. The present Rector, who is likewise, as already noticed, proprietor of the parish, the tithes of which are worth about 100l. a year, resides almost constantly with his family : and, as he is the occasion of infinite benefit to his poor people, so is he highly beloved and revered by them. He has a curate, also a married man : and the dwelling of the latter, once a miserable cabin, with its now neat enclosures, its well-glazed windows, and its little flower-garden, proves that any, however dreary a waste, may be converted into a home of comfort and peace, diffusing happiness around.

Mr. G.’s flower-garden is very pretty; it contained many plants, which seemed to flourish as well as on the main¬land, such as roses, carnations, and dahlias; and the multitude of primrose-roots on every bank, shows that in the Spring they are most abundant; but the sweet violet is not found except in Mrs. G.’s garden. There are no trees of any considerable height, even near the Mansion-House, where an attempt at planting has been made ; the narrow sort of copse with elder and stunted sycamore, scarcely serves to shelter the garden from the keen south-western blasts, but still they give a little clothing to the prospect just about the house : but an eye used to Irish scenery, particularly its fine rocky shores, does not miss trees so much as might be expected. Behind the garden, and almost perpendicularly above it, the rocks stand out in bold defiance, so as to protect all about home from the northern winds; on this rock I saw innumerable pigeons preening their wings, and disporting themselves in perfect contentment, enjoying the sun, which was as warmly shining as it does in more generally favoured climes. The pigeons are perfectly wild, but I could not learn if they were the Rock or the common Wood Pigeon.

SITUATION AND DIFFICULTY OF ACCESS.

THE Island of Raghery, Rathlin, or Rachlin, (for it is called by all these names indiscriminately, both by their neighbours on the mainland and by the natives,) is situated about five miles to the north of Ballycastle, a small town in the north-east corner of the county of Antrim, which was raised into some note in the early part of the last century by the fostering care of a spirited individual, Mr. Boyd, who spared no pains to improve his native place, and convert it from an insignificant fishing-village, into a flourishing manufacturing-town. Having accidentally discovered the shaft of an old coal-mine upon his estate, at the foot of the promontory of Fairhead, he proceeded to work it, and built a large glass-house on the sea-shore, as near as he conveniently could to the coal-pits. The numerous fine flints produced in the neighbourhood, as well as the sand in Ballycastle Bay, afforded him means of carrying on his operations at small expense. The demand for coals, and the need of hands to pick and sort the flints, to sift the sand, and to perform the other operations of the glass-house, caused a town to spring up around him. And that the good man might not have his undertaking incomplete, he built and endowed a chapel of ease for the growing town population. From causes, which Mr. Boyd did not anticipate, the prosperity of Ballycastle as a place of trade, has not continued. The collieries are almost at a stand; but the chapel remains for the accommodation of the inhabitants, being the building, the spire of which is seen in the accompanying sketch; and the glasshouse still resists the heavy blasts from the north, and the waves which often rise mountains high at the foot of the quay, which was built to protect the rising town from the inroads of the Northern Ocean.

This quay is the starting-place for those who would go to the island of Raghery, which lies due north of Ballycastle, stretching from the south-east or Ushet point, to the Bull Rocks at the south-western point of the island, about six miles. It is easily approached in fine weather by a smooth sandy shore towards the south, where the land recedes so as to take a crescent shape, thus forming a fine sheltered bay called Church Bay. Two other landing-places are used to the eastward, the Ushet and the Doon Points.

But every part is perfectly inaccessible in stormy weather, so that the inhabitants are not unfrequently for two or three weeks prisoners in the island, and perfectly unconscious of the affairs of their mainland neighbours, at the Winter season, or about the times of the equinoctial gales. But as there is no situation free from disagreeable circumstances, so is none without its advantages; and this stormy seclusion once saved the island from the miseries of civil war. In the unfortunate year 1798, when rebellion had broken out in every part of Ireland, and the inhabitants of the island of Raghery, generally peaceful and inoffensive as they are, were sworn to assist their mistaken neighbours on the mainland, one of those tremendous gales set in: the weather was not only stormy, but the whole coast was so enveloped in fog, that no signals could be discerned; nor could any boat either leave or approach the Isle of Raghery, till the misguided leaders of the rebellion in Ireland were subdued, and peace and tranquillity was re-established.

FIRST VISIT TO THE ISLAND.

IT was near the approach of the autumnal equinox, a few years ago, that we first visited the island of Raghery ; and we were ensured six hours of calm weather if we would immediately embark and be prepared to return within the time specified.

The sea was smooth as a mirror, as our light boat skimmed its surface: from the state of the tide, however we were unable to steer right across the channel from Ballycastle to Church Bay, the usual landing-place in Raghery; but kept along the Antrim coast towards the east, until we came close under the huge promontory of Benmore, or Fairhead, which is no-where seen to so great advantage as from the sea, whence it rises first in an angle of about forty-five degrees, and then in a perpendicular direction to the summit, where the rock is clothed with a beautiful carpeting of turf, moss, and wild-flowers, pleasing to the foot of the traveller, as the magnificent scenery around is most delightful to his eye. Fairhead is the first regular formation of basalt, which occurs in mass, and the existence of which is traced from the Cave Hill, near Belfast, and detected at intervals from thence to the eastward, on the chain of mountains which skirts the north side of the Lough of Belfast, till the headland takes a sudden turn to the north, near the rocks called the Gobbins. Again the basalt is found at various distances from the surface, all along the eastern coast of Antrim; but it assumes no regular form till Fairhead appears as another boundary to its progress eastward, being pushed forward, if I may so say, in primitive majesty, and overlooking westward the whole basaltic range, which commences at that headland, and occupying the northern coast of Ireland, is bounded only by the mountains of Donegall. Fairhead itself is a very noble object, as will appear to the reader from the sketch at the head of this article, taken from the Rectory-house of Ramoan, in which parish Ballycastle is situated; the town being in the foreground of the sketch, and the Mull of Cantire in the distance.

Many of the columnar stones which form this magnificent promontory, are said to be four hundred feet high; for the most part irregularly quadrangular, and continuous throughout their length, instead of being broken into joints, as is the case with those at the Giants’ Causeway, about ten miles to the west of Ballycastle, and at other detached masses observed more westward, and in the interior of the country. As this noble headland, however, is not immediately connected with my subject, except as it formed a feature on our passage to Raghery, and has been selected for the embellishment of this article, I will not detain the reader with more particulars, but refer him for further satisfaction to Hamilton’s Letters on the Coast of Antrim, and Conybeare’s Geological Account of the same; and proceed at once to the proper subject of this narrative.

I mentioned that, in consequence of the state of the tide, we were compelled, on our first visit to Raghery, to direct our course from Ballycastle to Fairhead, whence we were obliged to land at one of the eastern points, namely, the Ushet Point, and walk a distance of about two miles to the most habitable part of the island, where the proprietor’s house, the coast-guard station, and a few scattered fishermen’s cabins with the little church in the distance, form a sort of village-scene, highly picturesque and pleasing.

The walk was one of uncommon beauty and variety: rocks of every description of materials seemed in some places thrown together or broken into fragments in the greatest confusion, others looking as if chiselled and piled by the most skilful workmen, sometimes the hills on each side the narrow valley through which we passed, approached, or receded, now clothed with the most brilliant verdure, and now rugged and bare, scattering their crumbling ruins in the low ground, with every rough breeze or descending shower. About midway between Ushet and Church Bay, is a lovely little lake where the coot and the moorhen were rearing their still downy broods, and disporting themselves on its glassy surface ; a high red sand-bank close to the road, on one side of our path, was peopled with multitudes of the martin tribe who seemed to nestle and enjoy the plentiful supply of food engendered by this sheltered piece of water.

Our stay necessarily being very short, on reaching Church Bay, we could only run to the church and take some hasty refreshment at the proprietor’s house, when it was time to embark again. “ Be quick, be quick,” said the boatmen, “ we have no time to lose,” as I lingered on the shore to look around me, “ we shall but just save the tide.” Away then we went with the same soft air and glassy sea, and the view of the island we had left, and of Ireland as we approached it, was one of much grandeur and beauty. Fair Head, that magnificent promontory of Basalt, was seen in its full proportions, but softened by the slight haze of distance and the declining sun. Then, as we came nearer the coast of Ireland, the lights and shades were thrown across the indurated chalk cliffs of Kenbaan, standing forward in glittering whiteness to the westward, and further were stretching to the verge of the horizon the abrupt headlands of the Giants’ Causeway, the view being terminated in the distance by the island of Innishowen and the mountains of Donegal, nor were the Scottish islands to the east wanting, to finish the picture. As we neared the land, a small cloud came sweeping across the sky. We saw and admired its effects on the surrounding scenery. but before we had time to enjoy much of its beauties the sailors plied their oars, lowered the sails, and, in short, evinced that sort of restlessness which makes landsmen feel a little anxious to know what the careless-looking beings of a few moments ago can see to be so disturbed about. We flew over the waves, for waves we had now under us, till we got within the shelter of Kenbaan Head, beneath the high grounds of Clare, when almost as suddenly the men relaxed from their labours, and we were then in a calm, but not a glassy sea, for the short ripple showed that all was not as peaceful as it had been. We, however, landed at Ballycastle in safety, but before we were well off the landing-place, the waves dashed up and broke in white foam all around us. If we had not taken the precise time between tide and tide, we might have been detained several days before we could have reached the mainland; indeed, I was told that it was nearly three weeks before a boat could leave the island of Raghery after that evening, for the gale set in and raged with unabated fury for that time. I have mentioned our adventure to show, that, however this island is worth visiting, it requires more than common prudence and foresight, and withal, an entire dependence on the island boatmen, to choose your time, or you may be detained longer than it may be convenient to you, particularly as at present there is no house of public entertainment for the accommodation of travellers, except for the least fastidious pedestrian.

VISIT REPEATED IN 1835.—INHABITANTS.

LAST year, in the month of August, I had again the good fortune to be one of a party visiting Raghery ; when, as the kind proprietor and his family were at home, we had every facility of seeing more of the interior than we had on our former trip. Mr. G. had his boat ready for us, and himself was its steersman. The day on land was fine and promising, but the sea, though looking only pleasantly waved near Ballycastle, whence we again took boat, was considerably agitated when we got out into the channel free from the influence of the sheltering headlands of the bay, and exposed to the full force of the contending currents, as they swept round the many bold promontories of Ireland, meeting those which boil round the rocky capes of Raghery. However, after a rough but safe passage of two hours, we landed on the island, and were most hospitably received by the family of the proprietor.

Mr. G. combines the interesting characters of owner of the soil, rector of the parish, and the common master and friend of every creature within its bounds. His account of their character and conduct was very creditable to their general freedom from vice, and their peaceable and orderly behaviour: corresponding with the statement of Dr. Hamilton, who, in his “ Letters on the north coast of Antrim,” written about 1790, speaks of the inoffensive character of the inhabitants of Raghery, as well as the affectionate relative understanding between the master and his people. “ The tedious processes of civil law,” says Dr. H., are little known in Raghery ; and, indeed, the affection which the inhabitants bear to their landlord, whom they always speak of by the endearing name of master, together with their own simplicity of manners, renders the interference of the civil magistrate very unnecessary. The seizure of a cow or a horse for a few days, to bring the defaulter to a sense of his duty, or a copious draught of salt water from the surrounding ocean, in criminal cases, forms the greater part of the punishment on the island. If the offender be wicked beyond hope, banishment to Ireland is the last expedient resorted to, and soon frees the community from its pestilential member.”

Mr. G assured us that for the last forty years no heinous crime, deserving severe punishment, had been committed on the island : and no islander has ever seen even the outside walls of the county gaol.

It is indeed rather esteemed a hardship by the islanders, that they are required to contribute in this respect to the support of a building with which they have no concern, satisfied as they are to discharge the other legal demands to which they are liable. In answer to a question, whether any objections were made by them to the payment of tithes, the answer was. “ they object to no payment of any kind, except the county cess: but they do think it hard to pay a charge of 200 l., which is levied on the island for making roads in the County of Antrim, which they never travel, and for building and repairing the county-gaol, of which they have never seen even the outside walls.”

Agriculture is the principal employment of these islanders, but its operations did not appear to be carried on with judgment and skill. Much of the standing corn, particularly on the eastern side of the island, was intermixed and choked with weeds; the cow-rattle, the ox-eyed daisy, the rag-weed, and the broad-leaved sorrel, were conspicuous features in the furrows, and even made their appearance high up the ridges amongst the barley and oats. The holdings of the several tenants are very small: the appearance of the farmers and of the inhabitants in general is much the same as that of the people on the main land, and their habitations seem to possess the like scanty stock of the conveniences and comforts of life; but they have less numerous and active incentives to vice and misery, inasmuch as they have fewer whisky-shops, and are under the constant superintendence of their master’s eye, to check them by marks of displeasure, when they are known to have been guilty of any excess, and to encourage them with approbation whilst they continue to do well.

Inducements to greater industry have been lately given to the islanders, by means of the steam-packets which are continually passing on thoir way between Scotland and Ireland, and afford them opportunities, which formerly they did not enjoy, of disposing of the produce of their land and sea. They now catch large quantities of fish, for which they have a ready sale at their own doors, particularly lobsters and crabs. The collecting also of the different sorts of sea-weed employs a number of the women and children : some of this is burnt into kelp, and readily disposed of to the bleachers, and used not only in the Scotch and Irish linen-manufactories, but also in the whitening of calicoes and paper. The encouragement given of late years to the making of beds and mattresses from one of the Ulvae, commonly known as the riband-weed, is also likely to be an incitement to their industry, and to contribute to their domestick comforts by its produce.

The collecting of the sea-weed is the occasion of a very cheerful and entertaining scene. The people go down to the shore in troops, after the heavy gales, acting upon the ocean, have washed up the weeds from the bottom of the sea, or from some softer ground than the rocky shores of Raghery; and from the merry shouts and peals of laughter which I heard as I wandered near a party employed in the collection, it seems to be a great source of amusement to intercept the prey before the retiring wave shall have buried it again in the deep, or wafted it far away to other more fortunate lands. The weeds, being thus secured, are placed on sticks of every description, from the broom-handle to the roughest raft-wood, and so carried to the rocks which lie out of the reach of the next tide. They are there suspended, for the purpose of draining from them all the sea-moisture ; and the turning and exposing of them to the sun and wind requires constant attention, and affords employment to this class of the population.

HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE ISLAND.

OF the early history of Raghery, I am unable to offer much information: but in the ancient historical records of Ireland and Scotland, a few scattered notices occur, of this little spot, which have been collected by Sir James Ware, in his Antiquities of Ireland, and exhibited more recently by Dr. Hamilton, in his Letters on the Coast of Antrim, and by Archdale in his Wonasticon Hibernicum. For the present purpose, it may be sufficient to state the following particulars, the authorities for which may be found in the works just mentioned.

The island has been known by a great variety of names. By Pliny, who seems to have been the first to notice it, it is called Ricnea; by Ptolemy, in the time of the Antonines, Ricina; by Antoninus, Riduna. By the Irish historians, it is called at different times Recarn, and Recrain, and Rechran; Raghlina, and Raghlin; Raclinda; Raghery, and Raghry, by which last name Harris, in his edition of Ware’s Antiquities, says it was known in his day, namely, 1745; and as Archdale reports its appellation by the Irish antiquaries, Rochrinne, “ from the multitude of trees with which it abounded in ancient times.” The latter part of this word, “ Chrinne,” or something similar to it, I am told is the Irish word for tree. As to the etymological sense of the name here given to the island, I am incompetent to form an opinion ; but it is certainly remarkable how generally prevalent in Ireland is the persuasion of trees having formerly abounded in districts which are now altogether bare ; though the bogs bear ample testimony to the probability of the fact, from the frequent occurrence of large masses of timber, whose various species may be easily recognised; as the oak, the pine, the alder, and the yew, of former ages. Raghery is at present anything but “ abundant in trees.”

Except those in the immediate neighbourhood of Mr. G. s house, there is scarcely a tree to be found in the whole island, as large as a common-sized gooseberry-bush. There, a few stunted elders, enclosing some very small sycamores, which have been planted near thirty years, scarcely deserve the name of a copse. But as they do, nevertheless, form a screen to protect the garden from the south-east and south-west winds, they must not be passed entirely without notice ; though in any place but Raghery, or places similarly circumstanced, for instance, much of the sea-coast of Ireland, one would be hardly sensible of their existence.

A church is related to have been founded in this island by St. Columba, in the year of our Lord 541 : and to have been repaired in or about 630, by Segenius, abbot of Ja, or Hy, in Iona, who by some persons is said to have been its founder. But it was destroyed about 794, by the Danes, “ who then first infested the Irish and Scotch coasts, and particularly the Isle of Recran.” They laid waste the island with fire and sword, and in the general devastation the shrines and holy altars perished; so that, as a contemporary author writes, this and other islands about Ireland “had not so much as an anchorite on them.” To these invasions of the Danes are attributed the several remains of mounds or forts which are still found in Raghery, though scarcely more than a foundation of them can be traced at present. The accounts given by the inhabitants concerning these remains are so full of the marvellous, as to afford no satisfactory information: but the resemblance which they bear to other similar remnants of antiquity, which in several parts of Ireland are called “ Danish forts,” give probability to the opinion that these also are of Danish origin.

Without pretending to investigate the circumstances of Raghery during the succeeding ages, till after the invasion of Ireland by the English in the reign of King Henry the Second, I may observe, according to Ware, “ King John of England gave this island among other things to Alane de Galway, as we find in the records.” This must have been early in the thirteenth century, as John reigned from 1199 to 1216, having, however, been “Lord of Ireland” some years sooner. The next occurrence, with which it is connected, will give it a more interesting character with the general reader: for in 1306 it became a place of refuge to Robert Bruce, who is related by Buchanan, as cited by Dr. Hamilton, page 29, to have “ fled with a single companion to the Isle of Raghery, which is classed by Buchanan amongst the AEbude or Western Islands of Scotland, under the name of Raclinda.” Of this event, traditionary evidence is preserved in the island, substantiated by the ruins of a castle which afforded shelter and protection to the Scotch king, and is still known by the name of Bruce’s Castle. Sir Walter Scott in his Lord of the Isles, alludes to the event in the following lines :--

Suspicious doubt and lordly scorn

Lour’d in the haughty front of Lorn.

From underneath his brows of pride

The strange guests he sternly eyed,

And whispered closely what the ear

Of Argentine alone might hear:

Then question’d high and brief,

If in their voyage aught they knew

Of the rebellious Scottish crew,

Who to Rath-Erin’s shelter drew,

With Carrick’s outlaw’d chief?

And if, their Winter’s exile o’er,

They harbour’d still by Ulster’s shore,

Or launch’d their galleys on the main,

To vex their native land again ?

And he adds in a note, that “ the islanders at first fled from their new and armed guests; but upon some explanation submitted themselves to Bruce’s sovereignty. He resided among them until the approach of Spring, when he again returned to Scotland.”

If the fortress, the ruins of which now hear the name of Bruce, afforded him a refuge during his residence in the island, it must he of earlier date than 1306, the period of his sojourn there : for that this castle could not have been built by Bruce, seems evident from the facts of his having come to the island in the Winter, and leaving it in the following Spring. Concerning the builder, however, or the date, of the ruined fortress, not even a traditionary account now remains.

In 1551, the fifth year of king Edward the Sixth, a passing notice is made of the island, in connexion with the general disturbances of the North of Ireland.

Sir James Ware informs us, in his Annals (p. 114,) “ that Sir James Crofts, the Viceroy, marched against the rebelling Irish in Ulster, and their abettors, the Scotch islanders. From thence, to wit, from the town of Knockfergus, he sent some of his forces to the island of Raghlina by Ptolomy called Ricina, where they had very ill success, not a few of them being slain by the Scots, and one of his ships suffering wrack.”

In 1558, the sixth of Queen Mary, “ the Earl of Sussex, Lord-Lieutenant, returned out of England into Dublin with 500 armed soldiers, as well for the suppressing of rebels, as also of the robberies and pyracies of the islanders; in September,” as Ware goes on to say, (p. 145,) “ taking ship at Dalk, he sailed unto the Isle of Raghlin against the Scots. In that while that my Lord-Lieutenant was a landing, one of his vessels, by force of the tempest, was split near the shore, whereby some of the citizens of Dublin were swallowed up by the waves and perished. However, the Lord-Lieutenant himself, with the rest. landed, and having killed those that resisted, they wasted the island, and leading his forces from thence to Cantire, there made a vast destruction.”

In 1580, according to a MS. cited by Dr. Hamilton, (p. 124,) in consequence of a plot laid by the Irish M’Quillans, the proprietors of the neighbouring mainland, against a party of the Scotch M’Donalds, “ the Highlanders fled in the night-time, and escaped to the Island of Raghery, which not being inhabited at the time, they were forced to feed on colts’ flesh for want of other provisions.”

The war between the M’Donalds and the M’Quillans which ensued, and continued through the rest of the century, was terminated on their joint appeal to King James the First, soon after his succession to the English throne. Four great baronies were, thereupon, made over by patent to the M’Donalds; and the Isle of Raghlin appears from that time to have continued in undisturbed possession of that family, until it was transferred by sale, early in the last century, from the Earl of Antrim to the ancestor of Mr. Gage, the present proprietor.

To as late a period as the commencement of the last century, the island, though it contained about 500 inhabitants, had no resident clergyman, but was annexed to the parish of Ballintoy, on the mainland of the county of Antrim, about five miles to the west of Ballycastle. Dr.Francis Hutchinson, who succeeded to the Bishoprick ofDown and Connor in 1720, exerted himself to provide for the spiritual wants of these poor people: and in consequence the Rev. Dr. Archibald Stewart, Rector of Ballintoy, gave up the small tithes of Raghery, and the Trustees and Governors of Queen Anne’s Bounty, out of the First Fruits, bought the great tithes, as a provision for the future minister; and by means of subscriptions from the gentlemen and clergy in the neighbourhood, a new church was built on the ruins of an old one, the island being erected into a new parish. This event was commemorated by an inscription, painted on a board, and placed on the communion-table of the church. “ in honorem Dei Omnipotentis, Haec Ecclesia Sti. Thomse reaedificata fuit auspiciis, et ornata sumptibus, Reverendissimi in Christo Patris, Thomae, totius Hiberniae Primatis et Metropolitani, A.D. 1723.” (To the honour of Almighty God, this church of St. Thomas was rebuilt under the auspices, and adorned at the expense, of the most reverend Father in Christ, Thomas, Primate of all Ireland, and Metropolitan, in the year of our Lord 1723.) “My house shall be called an house of prayer for all people.” The Bishop also procured the Church Catechism to be translated into Irish and printed it in columns of English and Irish, calling it the Raghlin Catechism, built a parsonage house, and a good school for teaching English, and purchased, by contributions’ from himself and others, a collection of books for the incumbent. The church, which forms a conspicuous object in the prospect from the opposite coast, and on the intermediate passage, stands upon the edge of the sea, and gives the name of Church Bay to the curved shore on the southern side of the island.

From the above period the island has been under the pastoral care of its own parochial incumbent, so that the value of Bishop Hutchinson’s exertions is incalculable. The present Rector, who is likewise, as already noticed, proprietor of the parish, the tithes of which are worth about 100l. a year, resides almost constantly with his family : and, as he is the occasion of infinite benefit to his poor people, so is he highly beloved and revered by them. He has a curate, also a married man : and the dwelling of the latter, once a miserable cabin, with its now neat enclosures, its well-glazed windows, and its little flower-garden, proves that any, however dreary a waste, may be converted into a home of comfort and peace, diffusing happiness around.

Mr. G.’s flower-garden is very pretty; it contained many plants, which seemed to flourish as well as on the main¬land, such as roses, carnations, and dahlias; and the multitude of primrose-roots on every bank, shows that in the Spring they are most abundant; but the sweet violet is not found except in Mrs. G.’s garden. There are no trees of any considerable height, even near the Mansion-House, where an attempt at planting has been made ; the narrow sort of copse with elder and stunted sycamore, scarcely serves to shelter the garden from the keen south-western blasts, but still they give a little clothing to the prospect just about the house : but an eye used to Irish scenery, particularly its fine rocky shores, does not miss trees so much as might be expected. Behind the garden, and almost perpendicularly above it, the rocks stand out in bold defiance, so as to protect all about home from the northern winds; on this rock I saw innumerable pigeons preening their wings, and disporting themselves in perfect contentment, enjoying the sun, which was as warmly shining as it does in more generally favoured climes. The pigeons are perfectly wild, but I could not learn if they were the Rock or the common Wood Pigeon.

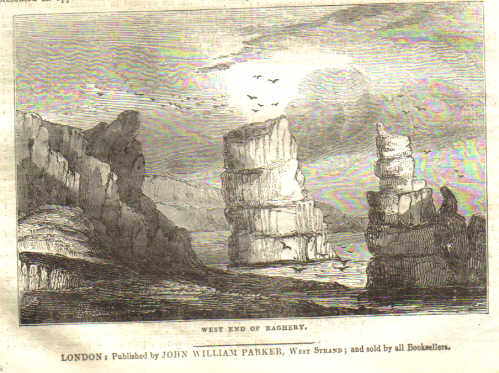

EXCURSION TO THE WESTERN SIDE OF THE ISLAND.

On the morning after our arrival we went with our kind host and hostess to see some of the scenery on the western side of the island. This part is very different from the other, both as to its inhabitants and its natural appearance; the western end, though rugged and bare in many parts, consisting of a variety of lime-stone, which is frequently clothed with a beautiful green-sward, whereas the eastern end consists altogether of basaltic rock, with little vegetable covering besides mosses and lichens This characteristic is noticed by Dr. Hamilton: — “ Small,” he observes, “ as this spot is, one can, nevertheless, trace two different characters among its inhabitants. The Kenramer, or eastern end, is craggy and mountainous: the land in the valleys is rich and well cultivated, but the coast destitute of harbours. Want of intercourse with strangers has preserved many peculiarities, and their native Irish continues to be the universal language. On the contrary, the Ushet end is barren in its soil, but more open, and well supplied with little harbours; hence the inhabitants are become fishermen, are accustomed to make short voyages, and to barter. Intercourse with strangers has rubbed off many of their peculiarities, and the English language is well understood, and generally spoken among them.” And Hamilton remarks thus on the difference of the natural appearance, on the eastern and western sides of the Island :—“ Let us now take a view of the coast of Raghery itself, from the lofty summit of Fairhead, which overlooks it. Westward we see its white cliffs rising abruptly from the ocean. Eastward we behold them (the white cliffs) dip to the level of the sea, and soon give place to many beautiful arrangements of basaltic pillars, which form the eastern end of the island.”

It was to the western side that we first went on the morning after our arrival. A wheel-carriage of any description, better than a common car without springs, is unknown in the island. The church being within a quarter of a mile of Mr. G.’s house, the family have no use for any such luxury, and the common car is better adapted for climbing the almost pathless mountains than a more refined vehicle. A brilliant green-sward, indeed, every now and then presented itself on our journey to the Kenramer Headland and Bull Rocks : but, as to roads, though there are some few smoothed and gravelled roods of land to lead to the principal collections of houses, or from one townland to another, much was as rough as if just made from a newly-opened quarry, or torn into shape by the mountain torrents, which sweep unresistingly down their precipitous sides : in short, roads more like the channel of a rapid stream when dried by summer heat.

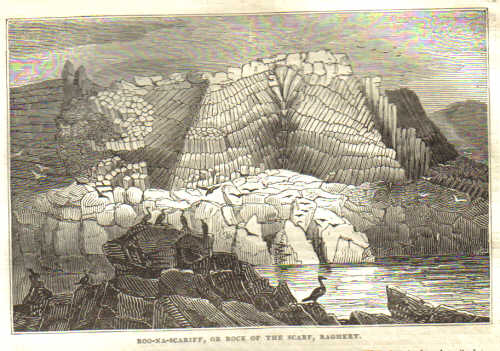

THE BULL ROCKS.

THE spot we went to visit is a collection of detached rocks standing out of the sea at about low-water mark, at the most western side of the island, terminating the Bull Point, and backed by the high and rugged precipices of Kenramer Head towering above them towards the north. On these grotesque rocks we saw and heard the most clamourous and motley troop of sea-birds crowded together; the puffins, the razor-bills, guillemots, and several varieties of gulls, which are in the habit of rearing their young here in the Spring, and remaining till the Autumn is considerably advanced, while the hoarse dashing of the waves below them seemed mocking their din and tumult. The scene was not unlike the description in Thomson’s Seasons:--

————— The cormorant on high

Wheels from the deep, and screams along the land.

Loud shrinks the soaring hern : and with wild wing

The circling sea-fowl cleave the flaky clouds.

Ocean, unequal press’d, with broken tide

And blind commotion heaves.

And the circumstance of these different birds building in Raghery, as in other similar situations, and the mode of building practised by the “ Puffins,” the “ Razor-bills,” and the “ Guillemots,” or Willocks, is thus described in a modern poem: --

Fain too the muse would stretch her flight

To the steep rocks of southern WIGHT,

Or where the straiten’d MENAI breaks

Round rugged PRIESTHOLM, or the peaks

Of craggy AILSA’S conelike pile,

Or northern RATHLIN’S simple isle:

There on the upright sea-cliff’s edge,

Along the bare and nestless ledge

Basaltick, or the cavern’d chalk,

The willock and the sharp-bill’d auk

Their marshall’d ranks collective close;

Range tiers on tiers, and rows on rows,

Their solitary eggs, and brave

The sweeping wind and dashing wave

Or deeply in the sandy shore

Their holes the burrowing puffins bore;

Sharp as the riving ploughshare, thrill

The furrow with their knife-like bill;

Scoop outward, as with hollow hand,

With palmate feet the muttering sand ;

And form a subterranean keep,

A winding chamber long and deep.

Mant’s British Months

One of the Rocks is called the Clough-na-Gallia, or Nurse and Baby. It has a very remarkable appearance from the headland on which we stood, and one could almost fancy the Nurse soothing and sheltering her Child from the pitiless waves beneath, and the clamourous sea-birds around her.

To those readers who are pleased with anecdotes of ornithology, it may be not uninteresting if I remark, that some of these wild sea-birds are capable of being in some decree tamed and domesticated. On our return to the house, two young guillemots were shown to us, lately taken almost fledged from the nest, for the purpose of being nursed up as others had been before, notwithstanding their incessant cries and other signs of restlessness when first taken. Sea-gulls have often been fed, sheltered, and tamed during the Winter, when found in a wounded or weak state late in the Autumn. In such cases they join their companions on their great gathering towards the breeding season, coming to and fro between their nestling places, and the places where they have been accustomed to be fed: and, perhaps, though they may not remain during the next Winter, they will in the following Spring return again, accompanied by their young, taking care, however, not to be again entrapped. Mrs. G. told me that a wounded gull, of the great black-backed species, had been known to return and feed with the common farm poultry for several seasons, where it had been kindly fostered during a long Winter, I saw several of the smaller sorts of gull, fearlessly feeding near one of the cabins or cottages, where they appeared to feel as part of the farming stock; though in evident awe of the lordly cock, who drove them away when they indulged too freely in the delicious morsels of fish and other garbage, thrown out with the potato skins from the family meal. Among the birds that inhabit or frequent the island, there are said to be a pair of eagles, which, however, we had not the good fortune to see, though their usual residence is amongst the rocks about Kenramer head. It is generally affirmed, with much appearance of seriousness and sincerity, by the common people, that should one of these birds be shot, or disappear by any other means for a considerable space of time, the survivor may be observed to remain in a state of sullen composure for several days, as if awaiting its companion’s return. After which it will leave the island; and having been absent for some days, or even perhaps for some weeks, will at length return with another mate, who will succeed to the property of the missing bird, taking possession of the same rock, and seeking its food over the same fishing-ground, in company with the survivor. A similar story is told of a pair of eagles, which bred on the opposite promontory of Fairhead or Benmore ; but the place to which the solitary bird resorts in search of a new mate cannot be mentioned. At the same time it seems to be a generally-received opinion, that more than two of these noble birds are never to be found residing in or near the same spot. While sailing through the air, the pair are said to keep apart from each other : yet at so small a distance, that one is seldom to be seen without an opportunity being given of seeing the other likewise, except when the female is actually occupied by incubation.

Abundant as Raghery is in some species of sea-birds, the ordinary British land-birds are but little known in the island, where, indeed, there is hardly any shelter for them. One species which they have, they will probably be soon glad to be released from, although it was at first welcomed and prized as a valuable acquisition. Magpies were not known there till about six or eight years ago, when a pair was first noticed, having accidentally straggled across the channel, and taken up their abode in the island. Being unmolested, in due course of time they began to increase and multiply, and there are now several pairs. It is said, that the magpie was unknown in Ireland till within the last century, when a pair was introduced into the country from England, the progeny of which now infests the whole land to a great extent, much to the annoyance of those who are not willing to sacrifice the riches of their poultry-yard and the music of their gardens for so discordant and unprofitable an intruder. They are not hitherto become such a nuisance in Raghery: where, however, their usual productiveness will probably be encouraged by their facility in procuring food from the eggs and young of the numberless sea-birds which frequent the island in the breeding season.

Other birds of the Pie kind are not unknown in the island. Rooks, though they do not, I apprehend, nestle there, visit it from a rookery near Ballycastle. At Kenramer my attention was taken by a pair of corbies or ravens : and the hooded or Royston crow is common here, as in other northern parts of the British islands, where the carrion crow, “ the crow” of the south, is a stranger, the name of “ the crow” by distinction being that which is appropriate to the hooded crow. The sea-shore, the rocks, the downy uplands, and the bogs of Raghery, would supply a considerable variety of wild plants to the botanist, at an earlier period of the year. On leaving the car near the Bull rocks to walk up the beautiful green mountain, we found several rather rare plants, such as the cotyledon, alchemilla, hydrocotyle, and on the rocks both the pink and yellow stone-crop; the rhodiola, or rose-root, also is a native of these mountains, but the season was past for its flowering.

UNCERTAINTY OF THE WEATHER FURTHER EXEMPLIFIED.—SUPERSTITIONS.

On my first visit to the island I noticed the uncertainty of its breezes. In the course of the night this was again fully proved, for soon after our return home, and before the evening had well closed in, the surges rose mountains high, and covered the shore with thick foam, while their broken spray dashed against the windows of the house for some hours. Some unfortunate fishermen early in the morning had their boat upset, not far from the spot we had gazed on with so much delight a few hours before, when scarcely a wave could tell of more than the sullen swell of the retiring tide. I grieve to say one poor fellow was drowned.

Though I mentioned the church and many agreeable particulars concerning it and its appointments, I omitted to say that the Romish creed, with its attendant superstitions, prevails in Raghery to a great extent. The dismay of the relatives of the poor drowned man that his body could not be found, and therefore could not be “ waked”, seemed to strike them with more horror than even his loss of life. The body could not be “ waked,” and the dread of purgatory for his poor soul was overpowering. The effect of their peculiar religious profession was painfully witnessed upon the present occasion. The incumbent of the parish and his family, aided by his curate, with their accustomed kind regard to all the inhabitants of whatever creed, carried to the survivors everything which seemed likely to minister to their wants, and tried every expedient to soothe them in their distress. But their endeavours appeared fruitless, in opposition to the inveterate prejudice implanted in them by their religious faith.

Another very curious instance of the island superstition, which recently occurred, may be here mentioned, as not unworthy of the reader’s attention. A clergyman, curate at the time to Mr. G., in one of his geological rambles, fell from the cliff above, not far from the Bull Rocks, amongst a cluster of rugged and pointed crags : his ancle was badly sprained, and otherwise he was much bruised. After having lain some considerable time without having the power to extricate himself from his painful and perilous situation, he heard the dashing of oars, and the sound of human voices : as he was at least two miles from his home, we may well conceive his pleasure at the welcome sounds. He called several times, — the sound of oars ceased. “ And who are you then at all,” said the boatmen; “ where are you?” “ I am here behind the rock,” adding its name of “ Sroin a Choin,” or “the Dog’s nose,” as the Irish name signifies in English. “ I am Mr. O’B., and I fell from the rocks above: I have hurt myself very much, and I cannot get out of this place without assistance.” Perhaps Mr. O’B. spoke this in a weak exhausted voice not like his usual firm tones. The poor fellows fell to crossing them¬selves, and muttering prayers to all the Saints they could think of. “Well,” said one of them, “perhaps it may be Mr. O’B.” The poor wounded curate, to quicken their motions, added, “Come and help me, and I will give you half a crown for your trouble.” Now half crowns are not so plentiful in the island as to be offered for a mere deed of humanity from one fellow-being to another: and to them it sounded so like one of the wiles of the arch-fiend himself from such a place, that they actually left the gentleman, disabled as he was, amidst the rocks. The curate, after-many hours of painful exertion, contrived to drag himself up to one of the nearest cabins, distant about half a mile from where he fell. He arrived in a state of complete exhaustion. When his strange adventure was told, Mr. G. was at first inclined to deal severely with the apparently-unfeeling fishermen. But when the poor ignorant creatures had told their own unvarnished tale, “ of their verily believing that they had been assailed by the temptation of the evil spirit in Mr. O’B’s. bodily shape,” he could only reason with them, and exhort them to a more humane caution in future ; and subjected them and their families to a punishment more home to their feelings than either fine or imprisonment: namely, a banishment from his house for two or three weeks. I should have said as something of an excuse for the poor boatmen, that the spot on which Mr. O'B. had fallen had an ill name, having been the grave of many an unfortunate boat’s crew, who had either taken shelter there, or had been washed in by the ever-eddying wave which foams and curls round its rocky enclosure. It is situated in a small bay, a little eastward of “the Bull,” called “Inan (or Eenan) Ronny,” meaning “ the Bay of the Brackens” or Ferns, which abound there.

But notwithstanding this and other effects of their superstitious belief, such as is apt to prevail among a scarcely civilized and sequestered people, the inhabitants are a kind-hearted, simple-minded race; little addicted to some, at least, of the vices of their neighbours on the mainland. Their honesty in their intercourse with each other appears commendable: and we were told that, if any article if value be at any time found on the mountains or the sea-shore, it is taken to the mansion-house, for the purpose of discovering the owner. An instance of this occurred during our excursion, when some shawls, which had fallen from the car, were taken to the house by a peasant child before our return thither.

Lying, as Raghery does, on the great road, as it were, for ships passing from Norway, Denmark, Scotland, and North America, as well as Coleraine and Derry, and exposed to frequent and most violent tempests, shipwrecks are unhappily of by no means rare occurrence. But not-withstanding the temptation thus sometimes thrown in the way of the inhabitants, instances are not known of their making prey of the shipwrecked mariner or his cargo. Both he and his merchandise are respected by the inhabitants in general. The master is immediately apprized of any article of value being cast on the coast; and the rites of hospitality are generously and unsparingly administered from the proprietor’s own stores. Some heart-rending scenes, arising out of disasters of this kind, have been now and again witnessed: and the wrecking of vessels within the sight of our friends has caused in them an involuntary shudder, when conversation has led to a mention of the circumstances. On the other hand, such occurrences have given occasion to them to feel the “luxury of doing good:” instances might be recited, where the entire crews of vessels have been saved, housed, and maintained for several days, till the winds and waves allowed of their transport to the mainland: and the offices and barns of the proprietor of the island have been the storehouses of shipwrecked merchandise, till an opportunity could be found for its safe removal.

Before quitting these cursory notices of the people of Raghery, another of their fanciful opinions, which they hold in common with other islanders, may be mentioned, as still prevailing there. A mermaid, I understand, has been seen near or on the island not many years ago. But whether she presented the poetical attribute of

- fair Ligea’s golden comb,

Wherewith she sits on diamond rocks,

Sleeking her soft alluring locks,

or appeared in the less graceful form of an ordinary seal, my informant did not particularize.

The existence of fairies is another article of belief with these remote islanders, their places of abode being supposed to be the mounds or forts, already noticed as remnants of the Danish incursions. If any of the stones belonging to these remains are moved, it is supposed that the offence thus committed against the “good people,” as these imaginary beings are denominated, with a suppressed voice indicating the fear of the speaker, will be visited by sickness on the offender or his family ; and should his cow or his pig suffer any ailment within even a considerable period after such delinquency, the visitation is attributed to the malignant influence of the same irritable and invisible people. This superstition they inherit from their forefathers, in common with their neighbours in the Highlands of Scotland, as described in the following extract from Collins’s beautiful ode: where, if the practice noticed m the former part of the extract does not prevail in Raghery, concerning which I have no recollection, the reader will not fail to notice in the latter part, the belief in the mischievous propensities of the “good people,” just ascribed to the islanders.

There must thou wake perforce thy Doric quill;

‘Tis Fancy’s land to which thou sett’st thy feet,

Where still, ‘tis said, the fairy people meet

Beneath each birken shade, on mead, or hill.

There each trim lass, that skims the milky store

To the swart tribes their creamy bowls allots;

By night they sip it round the cottage door.

While airy minstrels warble jocund notes.

There every herd by sad experience knows,

How, wing’d with fate, their elf-shot arrows fly,

When the sick ewe her summer food foregoes,

Or stretch’d on earth, the heart-smit heifers lie.

Such airy beings awe the untutor’d swain.———--

The “ elf-bolts” here specified, which are smooth, flat, sharp stones, probably used of old for military weapons, are sometimes found in Raghery, as well as on the Irish mainland : and the finding of one is regarded as an ill omen, foreboding injury to the finder.