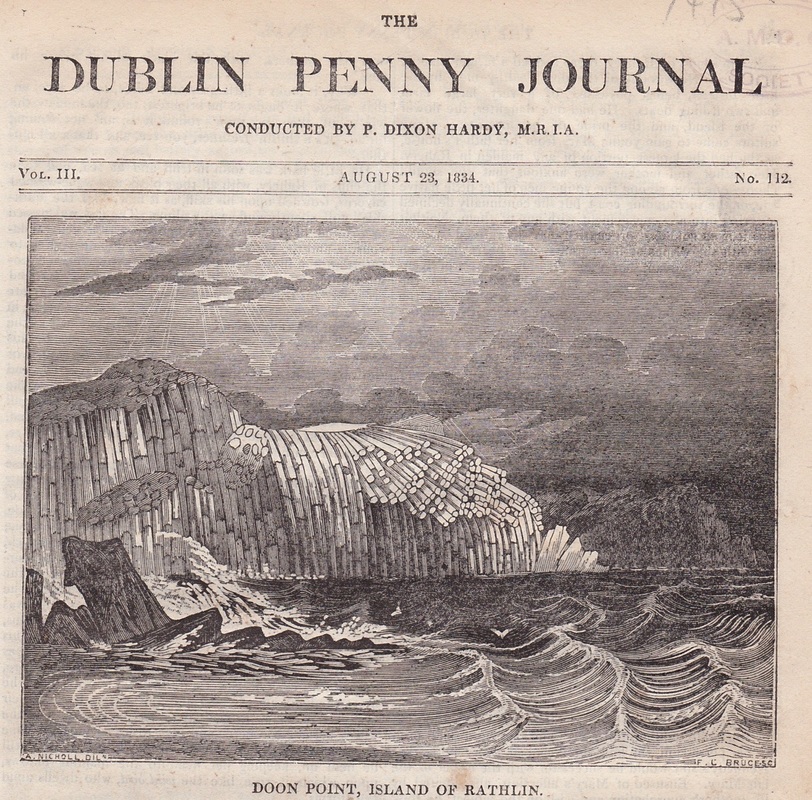

DOON POINT, ISLAND OF RATHLIN.

THE WIDOW’S WEDDING

Some half dozen miles from the coast of the County Antrim, and opposite to the bay of Ballycastle, rises, from the stormy ocean of the north, the island of Rahery.1 It is seldom visited now, in consequence of the wild turbulence of its rough shores, exposed on all sides to a rude surf; and the very irregular tides which ebb and flow around it. It is the Ricinia of Ptolemy, and Pliny calls it Ricnia. It is supposed by some to be the island mentioned by Antonius by the name of Reduna, but the Irish annalists and historians call it Racam. Buchanan calls it Raclinda, and Mackenzie mentions it by the name of Rachri, while Ware calls it Raghlin or Rathlin; but by the natives, and people of the coast of Antrim, it is universally called Rahery. It commands a wide extent of coast, and is the first land seen by vessels coming to our northern shores; and, in consequence, Mr. Hamilton thinks its etymon must be Ragh, or Rath-erin, the fort of Erin, or fortress of Ireland: and, as far as my little knowledge of the Irish language leads me to think, I agree with him, as most of the antient names were taken from the particular situation or feature of the place. The inhabitants are a poor simple race of people, and their island is not very productive. Rahery was a long time the resting place of the Scots in their expeditions, and their place of refuge in danger: it was also the place of assembly for the great northern chieftains, before making their descents on the Scotch or English coast. There are the ruins of a very old castle here, called Bruce’s castle, from its being the retreat of the famous hero, Robert Bruce, during the disturbances in Scotland at the time of Baliol. About the middle of the sixth century, the patron saint of the north, Columbus, otherwise Columkille, founded a religious establishment on the island of Rahery, which was destroyed by the Danes. In the year 975 they also plundered this island, and barbarously murdered St. Feradach, the abbot. The Scots held possession of it in 1558, but were attacked and driven out, with great slaughter, by the Lord Deputy, Sussex. The people of the coast and the island are all expert seamen, and at one time were famous smugglers, very much given to superstitious customs and observances. The Irish cobles of wicker-work, covered with a tarred and pitched horse-hide, were much in use here of old, and even still are sometimes seen skimming along, with their one or two conductors, in fine weather. And though I have said that the island is seldom visited, I did not wish to be understood as saying that there was not a constant communication between its inhabitants and the main shore; there is a kind of friendly intercourse subsists between them, and even in the most tempestuous weather, boats to and fro, are seen passing, despite of danger and difficulty.

In the island of Rahery there resided a farmer, named M’Cahan. He was one of the most wealthy men in the little district, being possessed of a very large farm and two fishing boats. He had one daughter, the flower of the island, and the pride of her parents. Many suitors came to gain young Mary from her father’s house, as she had the largest portion of any maiden in Rahery. Her father and mother were anxious that she should choose one from among the young men of her little native isle, or the surrounding coast, but she continually declined entering into any engagement with any of them. Neither was it from coldness or caprice that she refused to comply with the wishes of her parents - her heart had been smitten by the manly form and pleasing address of Kennedy O‘Neil, the son of a widow who resided on the mainland, near the cliffs of Ballycastle. She was in the habit, during summer weather, in company with a number of the young women and men of the island, to visit the opposite shores, and join in the dance with the villagers; in this way she first became acquainted with Kennedy, “mock na bointhee”, or, the widow’s son. His frank, obliging, and manly manners won upon the unsophisticated heart of the simple, yet tender and faithful islander. Kennedy was fondly attached to Mary, and the dance on Sunday without her, appeared the most monotonous and pleasure-less spot in the world.

The mother of Kennedy was one of those beings which are to be found in many parts of the country, even in this enlightened era - a believer in, and a practiser of, spells and charms, or, what is commonly called, a fairy woman. She professed the curing of all unaccountable and uncommon diseases, and which are attributed to the waywardness or malignity of that imaginary class of spiritual beings called fairies. Cattle suddenly taken ill, and children in a decline, or with pains or swellings, were taken to her, from a great distance, to “thry her skill on,” but whether she was successful in all her operations or not is more than can he said at present. She was feared and respected in the neighbourhood, and, at the same time, was considered one of the most useful personages within many miles of Ballycastle. She perceived, with delight, her son’s attachment to Mary M’Cahan, and encouraged it with all her soul: and being, as she boasted, of the "rale ould anshint race,” and having a small farm in her possession, she had, she imagined, every hope that Kennedy’s suit would be successful with the father of the fair Mary. Ensured of Mary’s affection, and incited by his mother’s approbation and wish on the subject, he took an opportunity of waiting on the farmer, and claiming her as his bride; but met with a decided and insulting refusal. This was a shock which his young and ardent nature was not prepared to meet, and which the proud heart and revengeful disposition of his mother could but ill brook. Mary was equally unprepared to meet it, for she had cherished hopes which were suddenly blighted; and her lover had pictured such warm scenes of domestic felicity, in the anticipated enjoyment of their homely fireside pleasures, that a second paradise of happiness had been opened to her young soul. Still hope, and promise of mutual affection, to be fairly and firmly kept, “for ever and a day," helped to reconcile them to what they considered the hardships of their situation.

Months glided by, and M‘Cahan was anxious to have his daughter married to some of the very respectable young men who proposed for her, but Mary modestly, yet firmly resisted every effort made to induce her to forego her promise to the mack na bointhee.

“Where are you goin’ the day, dear?" said the widow O’Neil to her son, as she perceived him fitting his tackle for the water one fine Sunday.

“Just over right to the island,” replied Kennedy.

“Stay at home, Kennedy, dear, then, this day,” said the mother.

"Didn’t I send word over' to Mary M’Cahan that I’d be over to the sport this evenin’? - throth did I," said Kennedy.

" There’s a storm to the nor-west this evenin’, then," said the mother; " an’ though fine the sun shines above us just now, God help the sail it ketches atween Rahery and the cliffs this evenin’, when he looks his last over the wathers, with the black clouds afore his face.” .

“Why, it looks a little grey and misty, to be sure, an that where it ought to be brightest, too, the foot ov the win’; but, then, it’s goin’ round it is, an’ not coming for’ad – it’s a shiftin’ freshner, you see, and that`s all mother.”

His little bark was soon in trim and at sea, and soon the cliffs of` Rahery, with all their bleak and wave-washed Caverns, frowned upon his skiff; as it flew, like the dark-sided gull, silently and swiftly along. The day was passed in a round of pleasure, for Kennedy was a general favourite, and the young men of the island endeavoured to entertain him in the best possible manner; and, as evening was closing, he had the happiness to “meet wi’ and greet wi'” his true and faithful Mary. Therefore, it was late before he thought of returning, and the sun was setting in the ocean before he stepped into his little “skimmer of the waves." The forebodings of the storm pointed by his mother, were now encreased into actual threatenings, of the very worst description. The wind had veered, and was sounding over the ocean, in the distance, like the moanings of a coming spirit, on an errand of misery and sorrow to mankind, while the ocean heaved and swelled, and the waves rolled heavily and forcibly to the shore, giving certain inclinations of the fury of the storm that was raging in the distance. Notwithstanding all these terrible omens, he launched his boat, and turned its tiny prow to the rising billows, and steered for the cliff of Ballycastle. The wind was partly against, and the tide, in its usual rapid manner, was rushing to mid-ocean; still Kennedy set his sail, and, taking a sweeping tack, stood away from the point of Rahery. Though appearances were very disheartening while in the shelter of the shore, yet as he stood far out, before the breeze, he trembled for the consequences of his rashness, and was sorry that he did not take the advice of his companions, and not have ventured out to sea that evenings. But his pride would not allow him to think of returning, for as he had the name of being the best sailor round the shore, it would fix itself as a stain on his character, should he fly to the land, after having put out to sea against their wishes. In the meantime the gale increased, and the waves became too fierce and high to leave almost a hope that his light frail bark could ever reach the shore; still he held on, keeping her head to the foaming billows, upon which it rose like the wild bird, who dwells amid the storms.

The winds now bellowed like the voices of many spirits, and the agitated deep, roused by their calls, answered by tossing its many crested waves to the clouds, and roared its responses to the furious element in tones of destruction and power. Kennedy, in taking in his small sail, lest his little bark should be overturned even by its breadth of canvass, was cast out, by one tremendous gust, into the howling waters; but, with the steadiness, firmness, and presence of mind, of a man used to meet danger and to combat it, he soon grasped the side of his dancing boat, but, in attempting to regain his position, her side was turned to the coming wave, which cast her over, and there she lay, in the trough of the sea, with her keel upwards. Even here Kennedy’s native courage and hardihood did not forsake him; he dived, and rose again just beside his upset and shivering vessel, upon which he seized with that desperate force which the fear of death supplies to the man in jeopardy. He clung to the keel with the tenacious grasp which one should lay upon their last hold of life, determined, while strength remained, to use every effort to preserve his existence. It was now dark night, and as his wreck would rise high upon the back of the yelling billows, he could discern the lights on shore, faint and dim in the distance, fainter and more dim than ever he had remarked them before -and the dreadful thought came across his mind, that the boat was driving out to sea, and that, if not swallowed up by the devouring waves during the storm, he would he left to perish, through weakness and excess of toil, far out in the ocean. Yet even still he determined to hold on, and trust in the goodness of what Almighty Being who caused the winds to blow, and the stormy waves to rage around him.

Towards morning the wind abated, and the waves subsided by degrees though now and then fierce gusts and mountain billows came, like the bursts of passion which break abruptly from the bosom of the angry, after their violent fit has poured the full rage of its wrath. The morning dawned, and when the harassed and terror stricken Kennedy looked around him, the land was in no place visible. He was alone, riding on the back of his upturned bark, a solitary living being amid the waste of waters. Despair filled his bosom; and, after having out-lived the terrors of the night-storm, he was about casting himself headlong into the deep, sooner than die a death of lingering and protracted agony; but hope, the ever-dweller in the human heart, came again, to his aid, and the thought of meeting some vessel coming from, or going to Belfast; or any of the northern ports made him resolve to preserve his life as long as possible. Nor was he disappointed, for towards evening a distant sail appeared coming in the direction in which he lay. Various hopes and fears now thronged, heavy and quick upon his mind - she might be going in a contrary direction - he might not; even if coming any way near her, be able to make himself observed. He took off his coarse blue jacket, and stripped off his shirt and red neck cloth, both of which he held as high as his hand would allow over his head; and when one hand would tire he would hold it in the other; On she came, and at length he was perceived, and a boat lowered, into which he was taken, exhausted and gasping. The ship belonged to a merchant in Belfast, and was taking a large cargo of fine linens and other goods to the West Indies. They were some leagues away even from the sight of land, and Kennedy had no other alternative but to make the voyage with them - a thing the master appeared to be very proud of; as he found, after leaving Belfast, that his complement of hands were too few to work the vessel.

In the morning the mother of Kennedy despatched a person to the island to inquire for her son; but no other account could he given, but that he had put to sea at night-fall, just as the storm was beginning. All round the bay of Ballycastle was explored, even for his corse, but not the slightest vestiges of him or his boat could be discovered. He was given up as lost, and the unfortunate mother was wild and loud in her grief and lamentations; nor were the sorrows of the faithful Mary less, though not so noisy; deep in the inmost recesses of her heart she deplored the loss of Kennedy, and the big tear rolling down her cheek, while pursuing even her household affairs, told plainly of

“The secret grief was at her heart.”

She pined, and the rose fled from her cheeks. She shunned the usual amusements in which she delighted, and gave herself up to melancholy. Her father and mother became anxious about her health, and wished, when it was too late, that they had given her to Kennedy O`Neil. They did everything to rouse her, in which, after some months, they succeeded; and she became more resigned and composed. Again they urged her to marry a very wealthy young man from the opposite shore, who had proposed for her hand, even before the supposed death of Kennedy. She gave a passive consent, and after some time they were married. ,She was anything but happy; she did her best to please and make her husband as happy as she could, but still there was a coldness and apathy in her manners which she could not banish; and though she did her best to be cheerful, yet still, in the midst of her efforts to appear gay, a chill would creep over her, and the thoughts of Kennedy Mock na Bointhee, and how he lost his life in coming to see her, would mar with sadness every attempt she made to please others, or appear happy herself. Four months after her marriage were scarcely elapsed, when her husband, who had been out fishing, quarreled with one of his companions as they were returning, and commenced fighting, even in the narrow boat. The other two men endeavoured to separate them, but without effect; and while the confusion reigned, the boat struck against a sunken rock, and the four men were ejected into the ocean, at the same time that the husband of Mary received a violent blow on the head with a boat-hook. The boat heeled with the shock, and immediately filled with water, and settled down beneath the wave as three men rose to the surface – but the husband of Mary never rose; stunned by the blow, he was unable to struggle when precipitated beneath the waves, and became the victim of his own rash and quarrelsome habits; Mary was now alone in the world, and possessed of; comparatively, a comfortable independence, and she determined never to marry again. Several proposals were made, but all rejected, with a firmness that told the solicitor that it would be useless to apply a second time. She remained in this state for nearly six months; and one' evening in the month of October, as the shortening autumn day was closing, a sailor, with a short stick in his hand; and a bundle slung on the end of it over his shoulder, made his appearance at the door, and addressing the servant maid, who was preparing the supper, requested a drink, and liberty to light his pipe.

“Walk in, Sir,” said Mary, who was employed at the other end of the house, with her back to the door.

The sailor started, and drawing back a few steps, surveyed the house from roof tree to foundation, and from end to end.

“Won’t you come in, Sir?” said the servant girl.

“No, no,” said he, “I thank you - I want nothing from you now;" and his tone was hurried and agitated and he turned away from the door, and ran like a man who had beheld some frightful; devouring monster, and from which he was trying to escape.

It was Kennedy O’Neil, Mock na Bointhee, who, after a variety of adventures during ten months, had returned to his native land with some little money, and high in the hope that he would find his Mary faithful, and ready to reward all his sufferings by becoming his wife.

“It is her,” said he to himself; after turning from her door, and when he had gained a sufficient composure to arrange his thoughts.

“It is her - I could not be mistaken in the voice or form - but I could not bear to look on her: and did she so soon forget me? not a twelve month gone, yet she is married, dear knows how long.- What`s the use in my coming home? I may as well turn back this moment and go to the Indies again” and he stopt, as if to return on his path: “but I must see my poor mother; and give her what I have gathered after my hardship and danger. Yes, she deserves it better from me than the false-hearted and the forgetful---the breaker of promises, and the betrayer. And is it of Mary M‘Cahan that I'm' obliged to say all these shameful things? Well, it`s no matter: “man proposes, but God disposes;” if she’s happy maybe it’s better for both her and me, for surely a stronger arm than poor mortyual man’s separated us in the beginning; and there’s a fate in marriage: but after all - all that passed between us - all that she promised me, and all that I promised her; and all the vows and hand an` words2 that she give me.” However - ‘what is to be, will be;’ and there’s no contending against a body’s luck: but Mary M‘Cahan, if I never knew you it would be better for me - that I know to my cost, anyhow.” - In such soliloquies and reflections was his mind occupied until he reached the cottage of his mother. It was dark and chilly; and mournfully the breeze blew from the sea with a wailing sound, and the booming of the distant ocean, intermingled with the hoarse and dashing noise of the breakers on the shore, served to add a gloom of an additional shade to his melancholy. His mother was sitting alone by her now desolate hearth - the last embers of the dying turf fire were flickering faintly from between two “ sods of turf” which were placed over them to inspire a renovated life into them, in order to preserve them for ‘ the morrow.’ She also held communion with her heart. “It was a curious dream,” she said, thinking alone; “and why should he come in that way to me, as if there was a joy to visit my old and withered heart, after the dark waves concealed him for ever from my sight. The dead can come no more to give gladness to the living; nor can the fallen tree ever be set upright amongst its companions in the thick wood, to bear green leaves and young branches; and why should he come to me in the disguise of joy, even in my dreams. He was not fond of tormenting or crossing me, and I know he would not wish to break my heart now entirely.” Here a rap of a particular kind at the outside made her start from her reverie. “Ha! my God! that rap! Oh, if it’s a warnin’ for me it’s welcome - I hope I am prepared to go; but maybe it’s some of the good people who want to catch me noddin’ - let them knock again;’ 3 and she listened with impatience, strongly mingled with superstitious fear, and again the knock was repeated more markedly than before, and again she became pained and agitated.

“I never in my life heard any thing so like; but it’s only to desave me the betther; so the sorra a latch I’ll rise, or a boult I’ll dhraw till it raps again, anyhow;” and again the rap was repeated with a certain degree of impatience, and she then approached the door with a cautious, stealthy step, and demanded who was there?

“Friend,” was the laconic reply; to which was added- “isn’t it a shame for you not to let a poor man in this hour of the night."

“Oh, gracious, it is his very voice. Speak - who are you?” she exclaimed, “for the love of goodness speak, and tell me who you are?”

“Who am I? Well, but that is a queer question to ask a man at his own mother`s door - who he is?” She uttered a loud scream, and endeavoured to spring to the door; but her emotions overpowered her, and her limbs refused to do their office, and down she fell upon the floor. Kennedy hearing the cry, burst open the door, and made every exertion in his power to reanimate the corpse-like figure of his mother, which he after some time effected. The meeting of the mother with the son, whom she now found, after believing him buried deep within the secret depths of the sea, was truly affecting. - It is impossible to describe a scene of this kind; but a man will feel the pleasure which such a sight must impart to the benevolent heart. The mother cried in frantic joy, and hung upon his neck, and wept over him. After the first paroxysm had abated, he described to her his wonderful and miraculous escape; and she thanked heaven for restoring to her her only child.

“But, mother,” said he, “there’s a great many changes have taken place since I left this.”

“It’s yourself that may say that, dear,” said the old wo-man, “ and not one of them for the better.”

“It`s you I believe, mother," said he; “I have not seen any improvement since I left it.”

“ No, dear; there’s the miners tearing up the earth at the ould head to look for coals; and there’s the polish (police) placed all round for fear we’d get a pinsworth from the say (sea), and there’s the ould castle there going to be levelled with the rock, for fear it id hide a bale, or a cask, and-”

“There`s_ Mary M‘Cahan marred, mother," said he convulsively.

“Yes, agra,” replied the mother;“ there’s no depending upon any one, or upon any thing in this deceiving world.”

“Well, mother, l’m only come just to see you, and bring you a little money to help to keep you comfortable, and then to bid you good bye, and then to go to seek my fortune again,”

“And are you going to leave me afther all, when I thought that God had pursarved you just to be the com-fort of my old days “

“I could not live here now mother; every thing is strange, and cold, and changed, and every thing looks worse than ever I saw it before - even you, mother, are sadly worn since I left you."

“And am I to lose you again? Why did you ever come to me, when my mind was settling after your loss, and God was making me reconciled to your death ?”

“But Mary M‘Cahan, mother, to forget me so soon; not one year till she got marred to another; would I do so ? No, never.”

“Yes, an’ its little comfort she had; for she did not long enjoy him; she was but four months marred till he was killed."

“And is she a widow now, mother? - ah, God help her l and who killed her husband ?"

“I did,” replied the mother. “Could I bear to see another where my son should be? No. I went to the sthream three nights, and I made a float of the flaggers4- I took from its grave, in the middle of the night, the skull and left hand of a child that never was christened. I dressed it up, and christened it by his name. I then put it into the float, with the hand tied to the ruddher, and sent it down the sthream, under the quiet moon and all the stars; ’twas racked (wrecked) at the fall of the rocks – ‘twas I done it - 'afore that day month he was murdhered’

The son shuddered as the mother concluded her horrifying recital, but he said nothing; he was accustomed to hear such things, and he firmly believed in their efficacy and power. However, his thoughts had undergone a material change since he heard that Mary was a widow. He promised to remain with his mother, for a while at least, and they retired for the night. Nothing could exceed the surprise and astonishment of the neighbourhood when the news was spread abroad the next morning, that Kennedy O’Neil was returned and some would not believe but that it was his mother who had redeemed him from fairy-land. All his old acquaintances flocked to see him, and hear his wonderful story, and every one had some news or another to tell him about Mary M‘Cahan. Week after week passed away, and he never made an attempt to see her, nor she to see him. At last, one evening as he was returning from the dance in the neighbouring village, a little warmed with the exercise, and heated with liquor, some strange sailors, belonging to a vessel that took shelter in the bay, for the purpose of refitting, had joined in the amusements, and had left the scene of gaiety sometime before him. As he walked on with a rapid step, he thought he heard cries at a distance before him on the road. The voice was that of a woman, and he hurried on, and soon came up to two ruffians in the garb of sailors, who were pulling a female between them, and whose piercing screams excited pity in his heart. He came up, and before they were aware of his approach, he felled one of the villains to the earth. The other immediately let go his hold, and grappled with Kennedy, and being a powerful man, the struggle was desperate; and 0’Neil felt, that though few in the country were his equals in the athletic exercises, that here at least he had met with his match. So, with surprising presence of mind, he seemed to yield by degrees before his antagonist, until the other, being almost sure of the victory, was thrown off his guard, when Kennedy, collecting all his strength for the effort, and stringing every nerve for the one push, placed his foot behind him, and flinging himself forward upon him, hurled him with irresistible force to the earth. The other, who was a small and light man, was recovering from the effects of the first blow, and preparing to attack him behind, when Kennedy, untired from the strife, turned on him with the fierce fury of an enraged tiger, and a second time felled him, senseless and bleeding, to the ground; and twisting an ash bough from a stunted tree that grew by the road side, he again prepared for the attack of the larger man, whom he knocked down three times in succession. At last they begged for mercy, and were permitted to depart. But what can be imagined as the surprise and astonishment of Kennedy on lifting the female, who had fainted, to find that it was his Mary. He laid his hand on her heart - it beat with life. He lifted her in his arms, and as her cottage was but at a short distance, he carried her home. On entering the cottage she came to her senses, and gazed about wildly until her eye rested upon Kennedy “It’s you then, Kennedy,” she said “that saved my life though I did not deserve the smallest kindness at your hand. Well, God is good, and brings every thing round, for his own wise purposes."

Kennedy gazed upon her. She was no longer the healthy, bright-eyed, and rosy girl, with the smile upon her lip, and gaiety and good humour in her bright blue eye. Her cheek was now pale, and her eye had lost its lustre, and Kennedy pitied the beautiful wreck - for she was still young and beautiful. They were alone; the conversation naturally verged towards old times; an explanation ensued, a reconciliation followed, and promises and vows were again renewed with double the fervour and truth of former years.

Kennedy told his mother of the circumstance; and she advised him, to prevent a recurrence of any accident or misfortune, to urge a speedy marriage. She wished to keep her son at home, for she feared he had acquired a taste for rambling during the time he had been away; besides, the idea of Mary’s comfortable farm, and the happy home her son would he master of, made her bosom dance with joy. Kennedy was but too anxious to follow her advice, and accordingly urged Mary to make him happy, pointing out the consequences that ensued from their first delay - how he had been driven away; how she was married; and how near she was being murdered, only that heaven sent him to her assistance. She consented, and the following Sunday was appointed for the ceremony to take place. The sailors who had been discomfitted in their attempt, made their case known to their comrades on board, and a confederacy was entered into by them to attack the house of Mary on the night of her marriage, while the guests were engaged with their mirth and revelry; and as they were to sail with the tide of that night, they might take their revenge in safety to themselves.

The mother of Kennedy could not be induced by any means to be present at the wedding; and when her son came to know the reason, and to endeavour to induce her, she merely replied –

Never mind me, Kennedy, dear ; you know that there is no one prouder to see you happy than your mother ; but there is something over me this evening, and you know I never do any thing without having good reason ; so never mind me, Kennedy, dear, I’ll see you early in the morning.”

Kennedy, who knew the eccentric turn of his mother, did not press her; and the festivities of the night were at their height: the rustic jest and the simple song passed round, and the whiskey flowed in brimmers, and all were merry and happy, when the mother of Kennedy, out of breath, and pale and panting with fatigue and terror, rushed in.

“For the sake of heaven, if you be men, stand and defend yourselves. The strange sailors have left the vessel, and are coming in a body to murder all before them, I ran over by the short cut, and roused the boys as I came along - but the sailors are not many perches from the door. The women began to scream, and the men to look about them, not knowing which side to turn.

“Hold your screaming throats," she said to the women, “and you stir about, and bar the door and windows, iv you have the spirit of men within yez ;” and she dragged a large oak table against the door. Kennedy leapt to his feet to assist her, and in a few minutes every portable article of furniture in the house was piled against the door and windows. “Now put out the lights,” said she, “and leave us in darkness.” The noise of the feet of many men advancing rapidly fell upon their ears, and in a few minutes a rap at the door announced their arrival.

“Don’t one of you speak a word,” said she.

A second rap, louder, echoed through the house, but no one stirred inside. The men were heard to whisper for a while, and then to try if the doors and windows were anyway accessible. They succeeded in breaking in some glass at the top of the window, to which one of them was elevated.

“Here, Kennedy,” said the mother, handing him the large kitchen tongs, “don’t let him tell what he seen when they take him back.”

Kennedy mounted upon a chair near the window, and as the man put in his head through the broken part, Kennedy struck him a terrible blow on the forehead, and he dropt back senseless into the arms of' his companions.

“Now shout," said the mother; and the men joined in one loud and simultaneous shout, which was answered by cries of revenge from the men outside, and a terrible rush was made against the door, which, however, defied all their efforts. The attack was renewed and redoubled with equal success, and cries were heard of ‘set fire to the house,' when the shouts and bustle of men coming along at a distance, made them pause. The men inside shouted, and they were answered by the villagers coming to their assistance.

“Now, boys," said Kennedy, “take the things from the door, and let us be ready to rush out upon them.”

But the sailors had anticipated their movement, and fled towards the shore, leaving the wounded man behind them. He was not killed; they took him into the house, and bathed his wound, and the farrier of the village bled him with his phleme. The rest of the night was spent in mirth and festivity. Kennedy and Mary lived happy together, and their wedding night was the most troublesome of the days and nights of their long and prosperous lives; and Kennedy often remarked, that it is happy for the man whose misfortunes come before marriage, and not after.

1. In our Guide to the Giant’s Causeway, published as a Supplement to our Second Volume, will be found a brief description of this interesting spot. The pillars are similar to those forming the Causeway, although by many esteemed much more curious, from the variety in the positions which they have assumed, of which the above engraving affords a very correct idea - some standing perpendicular, others lying on their sides, while the greater proportion of those on the top are bent or curved downwards.

2. In contracting or plighting their troths among the peasantry, the affair of pledging a hand and word is considered even more binding on the parties than the must solemn oath.

3. There is a superstition among the country people, that when a knock is heard at the door at night, it should never be opened until repeated three times.

4. The green flag-leaved annual that grows in marshy soils, and by the side of streams.

J. L. L.

THE WIDOW’S WEDDING

Some half dozen miles from the coast of the County Antrim, and opposite to the bay of Ballycastle, rises, from the stormy ocean of the north, the island of Rahery.1 It is seldom visited now, in consequence of the wild turbulence of its rough shores, exposed on all sides to a rude surf; and the very irregular tides which ebb and flow around it. It is the Ricinia of Ptolemy, and Pliny calls it Ricnia. It is supposed by some to be the island mentioned by Antonius by the name of Reduna, but the Irish annalists and historians call it Racam. Buchanan calls it Raclinda, and Mackenzie mentions it by the name of Rachri, while Ware calls it Raghlin or Rathlin; but by the natives, and people of the coast of Antrim, it is universally called Rahery. It commands a wide extent of coast, and is the first land seen by vessels coming to our northern shores; and, in consequence, Mr. Hamilton thinks its etymon must be Ragh, or Rath-erin, the fort of Erin, or fortress of Ireland: and, as far as my little knowledge of the Irish language leads me to think, I agree with him, as most of the antient names were taken from the particular situation or feature of the place. The inhabitants are a poor simple race of people, and their island is not very productive. Rahery was a long time the resting place of the Scots in their expeditions, and their place of refuge in danger: it was also the place of assembly for the great northern chieftains, before making their descents on the Scotch or English coast. There are the ruins of a very old castle here, called Bruce’s castle, from its being the retreat of the famous hero, Robert Bruce, during the disturbances in Scotland at the time of Baliol. About the middle of the sixth century, the patron saint of the north, Columbus, otherwise Columkille, founded a religious establishment on the island of Rahery, which was destroyed by the Danes. In the year 975 they also plundered this island, and barbarously murdered St. Feradach, the abbot. The Scots held possession of it in 1558, but were attacked and driven out, with great slaughter, by the Lord Deputy, Sussex. The people of the coast and the island are all expert seamen, and at one time were famous smugglers, very much given to superstitious customs and observances. The Irish cobles of wicker-work, covered with a tarred and pitched horse-hide, were much in use here of old, and even still are sometimes seen skimming along, with their one or two conductors, in fine weather. And though I have said that the island is seldom visited, I did not wish to be understood as saying that there was not a constant communication between its inhabitants and the main shore; there is a kind of friendly intercourse subsists between them, and even in the most tempestuous weather, boats to and fro, are seen passing, despite of danger and difficulty.

In the island of Rahery there resided a farmer, named M’Cahan. He was one of the most wealthy men in the little district, being possessed of a very large farm and two fishing boats. He had one daughter, the flower of the island, and the pride of her parents. Many suitors came to gain young Mary from her father’s house, as she had the largest portion of any maiden in Rahery. Her father and mother were anxious that she should choose one from among the young men of her little native isle, or the surrounding coast, but she continually declined entering into any engagement with any of them. Neither was it from coldness or caprice that she refused to comply with the wishes of her parents - her heart had been smitten by the manly form and pleasing address of Kennedy O‘Neil, the son of a widow who resided on the mainland, near the cliffs of Ballycastle. She was in the habit, during summer weather, in company with a number of the young women and men of the island, to visit the opposite shores, and join in the dance with the villagers; in this way she first became acquainted with Kennedy, “mock na bointhee”, or, the widow’s son. His frank, obliging, and manly manners won upon the unsophisticated heart of the simple, yet tender and faithful islander. Kennedy was fondly attached to Mary, and the dance on Sunday without her, appeared the most monotonous and pleasure-less spot in the world.

The mother of Kennedy was one of those beings which are to be found in many parts of the country, even in this enlightened era - a believer in, and a practiser of, spells and charms, or, what is commonly called, a fairy woman. She professed the curing of all unaccountable and uncommon diseases, and which are attributed to the waywardness or malignity of that imaginary class of spiritual beings called fairies. Cattle suddenly taken ill, and children in a decline, or with pains or swellings, were taken to her, from a great distance, to “thry her skill on,” but whether she was successful in all her operations or not is more than can he said at present. She was feared and respected in the neighbourhood, and, at the same time, was considered one of the most useful personages within many miles of Ballycastle. She perceived, with delight, her son’s attachment to Mary M’Cahan, and encouraged it with all her soul: and being, as she boasted, of the "rale ould anshint race,” and having a small farm in her possession, she had, she imagined, every hope that Kennedy’s suit would be successful with the father of the fair Mary. Ensured of Mary’s affection, and incited by his mother’s approbation and wish on the subject, he took an opportunity of waiting on the farmer, and claiming her as his bride; but met with a decided and insulting refusal. This was a shock which his young and ardent nature was not prepared to meet, and which the proud heart and revengeful disposition of his mother could but ill brook. Mary was equally unprepared to meet it, for she had cherished hopes which were suddenly blighted; and her lover had pictured such warm scenes of domestic felicity, in the anticipated enjoyment of their homely fireside pleasures, that a second paradise of happiness had been opened to her young soul. Still hope, and promise of mutual affection, to be fairly and firmly kept, “for ever and a day," helped to reconcile them to what they considered the hardships of their situation.

Months glided by, and M‘Cahan was anxious to have his daughter married to some of the very respectable young men who proposed for her, but Mary modestly, yet firmly resisted every effort made to induce her to forego her promise to the mack na bointhee.

“Where are you goin’ the day, dear?" said the widow O’Neil to her son, as she perceived him fitting his tackle for the water one fine Sunday.

“Just over right to the island,” replied Kennedy.

“Stay at home, Kennedy, dear, then, this day,” said the mother.

"Didn’t I send word over' to Mary M’Cahan that I’d be over to the sport this evenin’? - throth did I," said Kennedy.

" There’s a storm to the nor-west this evenin’, then," said the mother; " an’ though fine the sun shines above us just now, God help the sail it ketches atween Rahery and the cliffs this evenin’, when he looks his last over the wathers, with the black clouds afore his face.” .

“Why, it looks a little grey and misty, to be sure, an that where it ought to be brightest, too, the foot ov the win’; but, then, it’s goin’ round it is, an’ not coming for’ad – it’s a shiftin’ freshner, you see, and that`s all mother.”

His little bark was soon in trim and at sea, and soon the cliffs of` Rahery, with all their bleak and wave-washed Caverns, frowned upon his skiff; as it flew, like the dark-sided gull, silently and swiftly along. The day was passed in a round of pleasure, for Kennedy was a general favourite, and the young men of the island endeavoured to entertain him in the best possible manner; and, as evening was closing, he had the happiness to “meet wi’ and greet wi'” his true and faithful Mary. Therefore, it was late before he thought of returning, and the sun was setting in the ocean before he stepped into his little “skimmer of the waves." The forebodings of the storm pointed by his mother, were now encreased into actual threatenings, of the very worst description. The wind had veered, and was sounding over the ocean, in the distance, like the moanings of a coming spirit, on an errand of misery and sorrow to mankind, while the ocean heaved and swelled, and the waves rolled heavily and forcibly to the shore, giving certain inclinations of the fury of the storm that was raging in the distance. Notwithstanding all these terrible omens, he launched his boat, and turned its tiny prow to the rising billows, and steered for the cliff of Ballycastle. The wind was partly against, and the tide, in its usual rapid manner, was rushing to mid-ocean; still Kennedy set his sail, and, taking a sweeping tack, stood away from the point of Rahery. Though appearances were very disheartening while in the shelter of the shore, yet as he stood far out, before the breeze, he trembled for the consequences of his rashness, and was sorry that he did not take the advice of his companions, and not have ventured out to sea that evenings. But his pride would not allow him to think of returning, for as he had the name of being the best sailor round the shore, it would fix itself as a stain on his character, should he fly to the land, after having put out to sea against their wishes. In the meantime the gale increased, and the waves became too fierce and high to leave almost a hope that his light frail bark could ever reach the shore; still he held on, keeping her head to the foaming billows, upon which it rose like the wild bird, who dwells amid the storms.

The winds now bellowed like the voices of many spirits, and the agitated deep, roused by their calls, answered by tossing its many crested waves to the clouds, and roared its responses to the furious element in tones of destruction and power. Kennedy, in taking in his small sail, lest his little bark should be overturned even by its breadth of canvass, was cast out, by one tremendous gust, into the howling waters; but, with the steadiness, firmness, and presence of mind, of a man used to meet danger and to combat it, he soon grasped the side of his dancing boat, but, in attempting to regain his position, her side was turned to the coming wave, which cast her over, and there she lay, in the trough of the sea, with her keel upwards. Even here Kennedy’s native courage and hardihood did not forsake him; he dived, and rose again just beside his upset and shivering vessel, upon which he seized with that desperate force which the fear of death supplies to the man in jeopardy. He clung to the keel with the tenacious grasp which one should lay upon their last hold of life, determined, while strength remained, to use every effort to preserve his existence. It was now dark night, and as his wreck would rise high upon the back of the yelling billows, he could discern the lights on shore, faint and dim in the distance, fainter and more dim than ever he had remarked them before -and the dreadful thought came across his mind, that the boat was driving out to sea, and that, if not swallowed up by the devouring waves during the storm, he would he left to perish, through weakness and excess of toil, far out in the ocean. Yet even still he determined to hold on, and trust in the goodness of what Almighty Being who caused the winds to blow, and the stormy waves to rage around him.

Towards morning the wind abated, and the waves subsided by degrees though now and then fierce gusts and mountain billows came, like the bursts of passion which break abruptly from the bosom of the angry, after their violent fit has poured the full rage of its wrath. The morning dawned, and when the harassed and terror stricken Kennedy looked around him, the land was in no place visible. He was alone, riding on the back of his upturned bark, a solitary living being amid the waste of waters. Despair filled his bosom; and, after having out-lived the terrors of the night-storm, he was about casting himself headlong into the deep, sooner than die a death of lingering and protracted agony; but hope, the ever-dweller in the human heart, came again, to his aid, and the thought of meeting some vessel coming from, or going to Belfast; or any of the northern ports made him resolve to preserve his life as long as possible. Nor was he disappointed, for towards evening a distant sail appeared coming in the direction in which he lay. Various hopes and fears now thronged, heavy and quick upon his mind - she might be going in a contrary direction - he might not; even if coming any way near her, be able to make himself observed. He took off his coarse blue jacket, and stripped off his shirt and red neck cloth, both of which he held as high as his hand would allow over his head; and when one hand would tire he would hold it in the other; On she came, and at length he was perceived, and a boat lowered, into which he was taken, exhausted and gasping. The ship belonged to a merchant in Belfast, and was taking a large cargo of fine linens and other goods to the West Indies. They were some leagues away even from the sight of land, and Kennedy had no other alternative but to make the voyage with them - a thing the master appeared to be very proud of; as he found, after leaving Belfast, that his complement of hands were too few to work the vessel.

In the morning the mother of Kennedy despatched a person to the island to inquire for her son; but no other account could he given, but that he had put to sea at night-fall, just as the storm was beginning. All round the bay of Ballycastle was explored, even for his corse, but not the slightest vestiges of him or his boat could be discovered. He was given up as lost, and the unfortunate mother was wild and loud in her grief and lamentations; nor were the sorrows of the faithful Mary less, though not so noisy; deep in the inmost recesses of her heart she deplored the loss of Kennedy, and the big tear rolling down her cheek, while pursuing even her household affairs, told plainly of

“The secret grief was at her heart.”

She pined, and the rose fled from her cheeks. She shunned the usual amusements in which she delighted, and gave herself up to melancholy. Her father and mother became anxious about her health, and wished, when it was too late, that they had given her to Kennedy O`Neil. They did everything to rouse her, in which, after some months, they succeeded; and she became more resigned and composed. Again they urged her to marry a very wealthy young man from the opposite shore, who had proposed for her hand, even before the supposed death of Kennedy. She gave a passive consent, and after some time they were married. ,She was anything but happy; she did her best to please and make her husband as happy as she could, but still there was a coldness and apathy in her manners which she could not banish; and though she did her best to be cheerful, yet still, in the midst of her efforts to appear gay, a chill would creep over her, and the thoughts of Kennedy Mock na Bointhee, and how he lost his life in coming to see her, would mar with sadness every attempt she made to please others, or appear happy herself. Four months after her marriage were scarcely elapsed, when her husband, who had been out fishing, quarreled with one of his companions as they were returning, and commenced fighting, even in the narrow boat. The other two men endeavoured to separate them, but without effect; and while the confusion reigned, the boat struck against a sunken rock, and the four men were ejected into the ocean, at the same time that the husband of Mary received a violent blow on the head with a boat-hook. The boat heeled with the shock, and immediately filled with water, and settled down beneath the wave as three men rose to the surface – but the husband of Mary never rose; stunned by the blow, he was unable to struggle when precipitated beneath the waves, and became the victim of his own rash and quarrelsome habits; Mary was now alone in the world, and possessed of; comparatively, a comfortable independence, and she determined never to marry again. Several proposals were made, but all rejected, with a firmness that told the solicitor that it would be useless to apply a second time. She remained in this state for nearly six months; and one' evening in the month of October, as the shortening autumn day was closing, a sailor, with a short stick in his hand; and a bundle slung on the end of it over his shoulder, made his appearance at the door, and addressing the servant maid, who was preparing the supper, requested a drink, and liberty to light his pipe.

“Walk in, Sir,” said Mary, who was employed at the other end of the house, with her back to the door.

The sailor started, and drawing back a few steps, surveyed the house from roof tree to foundation, and from end to end.

“Won’t you come in, Sir?” said the servant girl.

“No, no,” said he, “I thank you - I want nothing from you now;" and his tone was hurried and agitated and he turned away from the door, and ran like a man who had beheld some frightful; devouring monster, and from which he was trying to escape.

It was Kennedy O’Neil, Mock na Bointhee, who, after a variety of adventures during ten months, had returned to his native land with some little money, and high in the hope that he would find his Mary faithful, and ready to reward all his sufferings by becoming his wife.

“It is her,” said he to himself; after turning from her door, and when he had gained a sufficient composure to arrange his thoughts.

“It is her - I could not be mistaken in the voice or form - but I could not bear to look on her: and did she so soon forget me? not a twelve month gone, yet she is married, dear knows how long.- What`s the use in my coming home? I may as well turn back this moment and go to the Indies again” and he stopt, as if to return on his path: “but I must see my poor mother; and give her what I have gathered after my hardship and danger. Yes, she deserves it better from me than the false-hearted and the forgetful---the breaker of promises, and the betrayer. And is it of Mary M‘Cahan that I'm' obliged to say all these shameful things? Well, it`s no matter: “man proposes, but God disposes;” if she’s happy maybe it’s better for both her and me, for surely a stronger arm than poor mortyual man’s separated us in the beginning; and there’s a fate in marriage: but after all - all that passed between us - all that she promised me, and all that I promised her; and all the vows and hand an` words2 that she give me.” However - ‘what is to be, will be;’ and there’s no contending against a body’s luck: but Mary M‘Cahan, if I never knew you it would be better for me - that I know to my cost, anyhow.” - In such soliloquies and reflections was his mind occupied until he reached the cottage of his mother. It was dark and chilly; and mournfully the breeze blew from the sea with a wailing sound, and the booming of the distant ocean, intermingled with the hoarse and dashing noise of the breakers on the shore, served to add a gloom of an additional shade to his melancholy. His mother was sitting alone by her now desolate hearth - the last embers of the dying turf fire were flickering faintly from between two “ sods of turf” which were placed over them to inspire a renovated life into them, in order to preserve them for ‘ the morrow.’ She also held communion with her heart. “It was a curious dream,” she said, thinking alone; “and why should he come in that way to me, as if there was a joy to visit my old and withered heart, after the dark waves concealed him for ever from my sight. The dead can come no more to give gladness to the living; nor can the fallen tree ever be set upright amongst its companions in the thick wood, to bear green leaves and young branches; and why should he come to me in the disguise of joy, even in my dreams. He was not fond of tormenting or crossing me, and I know he would not wish to break my heart now entirely.” Here a rap of a particular kind at the outside made her start from her reverie. “Ha! my God! that rap! Oh, if it’s a warnin’ for me it’s welcome - I hope I am prepared to go; but maybe it’s some of the good people who want to catch me noddin’ - let them knock again;’ 3 and she listened with impatience, strongly mingled with superstitious fear, and again the knock was repeated more markedly than before, and again she became pained and agitated.

“I never in my life heard any thing so like; but it’s only to desave me the betther; so the sorra a latch I’ll rise, or a boult I’ll dhraw till it raps again, anyhow;” and again the rap was repeated with a certain degree of impatience, and she then approached the door with a cautious, stealthy step, and demanded who was there?

“Friend,” was the laconic reply; to which was added- “isn’t it a shame for you not to let a poor man in this hour of the night."

“Oh, gracious, it is his very voice. Speak - who are you?” she exclaimed, “for the love of goodness speak, and tell me who you are?”

“Who am I? Well, but that is a queer question to ask a man at his own mother`s door - who he is?” She uttered a loud scream, and endeavoured to spring to the door; but her emotions overpowered her, and her limbs refused to do their office, and down she fell upon the floor. Kennedy hearing the cry, burst open the door, and made every exertion in his power to reanimate the corpse-like figure of his mother, which he after some time effected. The meeting of the mother with the son, whom she now found, after believing him buried deep within the secret depths of the sea, was truly affecting. - It is impossible to describe a scene of this kind; but a man will feel the pleasure which such a sight must impart to the benevolent heart. The mother cried in frantic joy, and hung upon his neck, and wept over him. After the first paroxysm had abated, he described to her his wonderful and miraculous escape; and she thanked heaven for restoring to her her only child.

“But, mother,” said he, “there’s a great many changes have taken place since I left this.”

“It’s yourself that may say that, dear,” said the old wo-man, “ and not one of them for the better.”

“It`s you I believe, mother," said he; “I have not seen any improvement since I left it.”

“ No, dear; there’s the miners tearing up the earth at the ould head to look for coals; and there’s the polish (police) placed all round for fear we’d get a pinsworth from the say (sea), and there’s the ould castle there going to be levelled with the rock, for fear it id hide a bale, or a cask, and-”

“There`s_ Mary M‘Cahan marred, mother," said he convulsively.

“Yes, agra,” replied the mother;“ there’s no depending upon any one, or upon any thing in this deceiving world.”

“Well, mother, l’m only come just to see you, and bring you a little money to help to keep you comfortable, and then to bid you good bye, and then to go to seek my fortune again,”

“And are you going to leave me afther all, when I thought that God had pursarved you just to be the com-fort of my old days “

“I could not live here now mother; every thing is strange, and cold, and changed, and every thing looks worse than ever I saw it before - even you, mother, are sadly worn since I left you."

“And am I to lose you again? Why did you ever come to me, when my mind was settling after your loss, and God was making me reconciled to your death ?”

“But Mary M‘Cahan, mother, to forget me so soon; not one year till she got marred to another; would I do so ? No, never.”

“Yes, an’ its little comfort she had; for she did not long enjoy him; she was but four months marred till he was killed."

“And is she a widow now, mother? - ah, God help her l and who killed her husband ?"

“I did,” replied the mother. “Could I bear to see another where my son should be? No. I went to the sthream three nights, and I made a float of the flaggers4- I took from its grave, in the middle of the night, the skull and left hand of a child that never was christened. I dressed it up, and christened it by his name. I then put it into the float, with the hand tied to the ruddher, and sent it down the sthream, under the quiet moon and all the stars; ’twas racked (wrecked) at the fall of the rocks – ‘twas I done it - 'afore that day month he was murdhered’

The son shuddered as the mother concluded her horrifying recital, but he said nothing; he was accustomed to hear such things, and he firmly believed in their efficacy and power. However, his thoughts had undergone a material change since he heard that Mary was a widow. He promised to remain with his mother, for a while at least, and they retired for the night. Nothing could exceed the surprise and astonishment of the neighbourhood when the news was spread abroad the next morning, that Kennedy O’Neil was returned and some would not believe but that it was his mother who had redeemed him from fairy-land. All his old acquaintances flocked to see him, and hear his wonderful story, and every one had some news or another to tell him about Mary M‘Cahan. Week after week passed away, and he never made an attempt to see her, nor she to see him. At last, one evening as he was returning from the dance in the neighbouring village, a little warmed with the exercise, and heated with liquor, some strange sailors, belonging to a vessel that took shelter in the bay, for the purpose of refitting, had joined in the amusements, and had left the scene of gaiety sometime before him. As he walked on with a rapid step, he thought he heard cries at a distance before him on the road. The voice was that of a woman, and he hurried on, and soon came up to two ruffians in the garb of sailors, who were pulling a female between them, and whose piercing screams excited pity in his heart. He came up, and before they were aware of his approach, he felled one of the villains to the earth. The other immediately let go his hold, and grappled with Kennedy, and being a powerful man, the struggle was desperate; and 0’Neil felt, that though few in the country were his equals in the athletic exercises, that here at least he had met with his match. So, with surprising presence of mind, he seemed to yield by degrees before his antagonist, until the other, being almost sure of the victory, was thrown off his guard, when Kennedy, collecting all his strength for the effort, and stringing every nerve for the one push, placed his foot behind him, and flinging himself forward upon him, hurled him with irresistible force to the earth. The other, who was a small and light man, was recovering from the effects of the first blow, and preparing to attack him behind, when Kennedy, untired from the strife, turned on him with the fierce fury of an enraged tiger, and a second time felled him, senseless and bleeding, to the ground; and twisting an ash bough from a stunted tree that grew by the road side, he again prepared for the attack of the larger man, whom he knocked down three times in succession. At last they begged for mercy, and were permitted to depart. But what can be imagined as the surprise and astonishment of Kennedy on lifting the female, who had fainted, to find that it was his Mary. He laid his hand on her heart - it beat with life. He lifted her in his arms, and as her cottage was but at a short distance, he carried her home. On entering the cottage she came to her senses, and gazed about wildly until her eye rested upon Kennedy “It’s you then, Kennedy,” she said “that saved my life though I did not deserve the smallest kindness at your hand. Well, God is good, and brings every thing round, for his own wise purposes."

Kennedy gazed upon her. She was no longer the healthy, bright-eyed, and rosy girl, with the smile upon her lip, and gaiety and good humour in her bright blue eye. Her cheek was now pale, and her eye had lost its lustre, and Kennedy pitied the beautiful wreck - for she was still young and beautiful. They were alone; the conversation naturally verged towards old times; an explanation ensued, a reconciliation followed, and promises and vows were again renewed with double the fervour and truth of former years.

Kennedy told his mother of the circumstance; and she advised him, to prevent a recurrence of any accident or misfortune, to urge a speedy marriage. She wished to keep her son at home, for she feared he had acquired a taste for rambling during the time he had been away; besides, the idea of Mary’s comfortable farm, and the happy home her son would he master of, made her bosom dance with joy. Kennedy was but too anxious to follow her advice, and accordingly urged Mary to make him happy, pointing out the consequences that ensued from their first delay - how he had been driven away; how she was married; and how near she was being murdered, only that heaven sent him to her assistance. She consented, and the following Sunday was appointed for the ceremony to take place. The sailors who had been discomfitted in their attempt, made their case known to their comrades on board, and a confederacy was entered into by them to attack the house of Mary on the night of her marriage, while the guests were engaged with their mirth and revelry; and as they were to sail with the tide of that night, they might take their revenge in safety to themselves.

The mother of Kennedy could not be induced by any means to be present at the wedding; and when her son came to know the reason, and to endeavour to induce her, she merely replied –

Never mind me, Kennedy, dear ; you know that there is no one prouder to see you happy than your mother ; but there is something over me this evening, and you know I never do any thing without having good reason ; so never mind me, Kennedy, dear, I’ll see you early in the morning.”

Kennedy, who knew the eccentric turn of his mother, did not press her; and the festivities of the night were at their height: the rustic jest and the simple song passed round, and the whiskey flowed in brimmers, and all were merry and happy, when the mother of Kennedy, out of breath, and pale and panting with fatigue and terror, rushed in.

“For the sake of heaven, if you be men, stand and defend yourselves. The strange sailors have left the vessel, and are coming in a body to murder all before them, I ran over by the short cut, and roused the boys as I came along - but the sailors are not many perches from the door. The women began to scream, and the men to look about them, not knowing which side to turn.

“Hold your screaming throats," she said to the women, “and you stir about, and bar the door and windows, iv you have the spirit of men within yez ;” and she dragged a large oak table against the door. Kennedy leapt to his feet to assist her, and in a few minutes every portable article of furniture in the house was piled against the door and windows. “Now put out the lights,” said she, “and leave us in darkness.” The noise of the feet of many men advancing rapidly fell upon their ears, and in a few minutes a rap at the door announced their arrival.

“Don’t one of you speak a word,” said she.

A second rap, louder, echoed through the house, but no one stirred inside. The men were heard to whisper for a while, and then to try if the doors and windows were anyway accessible. They succeeded in breaking in some glass at the top of the window, to which one of them was elevated.

“Here, Kennedy,” said the mother, handing him the large kitchen tongs, “don’t let him tell what he seen when they take him back.”

Kennedy mounted upon a chair near the window, and as the man put in his head through the broken part, Kennedy struck him a terrible blow on the forehead, and he dropt back senseless into the arms of' his companions.

“Now shout," said the mother; and the men joined in one loud and simultaneous shout, which was answered by cries of revenge from the men outside, and a terrible rush was made against the door, which, however, defied all their efforts. The attack was renewed and redoubled with equal success, and cries were heard of ‘set fire to the house,' when the shouts and bustle of men coming along at a distance, made them pause. The men inside shouted, and they were answered by the villagers coming to their assistance.

“Now, boys," said Kennedy, “take the things from the door, and let us be ready to rush out upon them.”

But the sailors had anticipated their movement, and fled towards the shore, leaving the wounded man behind them. He was not killed; they took him into the house, and bathed his wound, and the farrier of the village bled him with his phleme. The rest of the night was spent in mirth and festivity. Kennedy and Mary lived happy together, and their wedding night was the most troublesome of the days and nights of their long and prosperous lives; and Kennedy often remarked, that it is happy for the man whose misfortunes come before marriage, and not after.

1. In our Guide to the Giant’s Causeway, published as a Supplement to our Second Volume, will be found a brief description of this interesting spot. The pillars are similar to those forming the Causeway, although by many esteemed much more curious, from the variety in the positions which they have assumed, of which the above engraving affords a very correct idea - some standing perpendicular, others lying on their sides, while the greater proportion of those on the top are bent or curved downwards.

2. In contracting or plighting their troths among the peasantry, the affair of pledging a hand and word is considered even more binding on the parties than the must solemn oath.

3. There is a superstition among the country people, that when a knock is heard at the door at night, it should never be opened until repeated three times.

4. The green flag-leaved annual that grows in marshy soils, and by the side of streams.

J. L. L.