A Guide to

THE GIANT'S CAUSEWAY

being a supplement

to the second volume of the

DUBLIN PENNY JOURNAL

THE GIANT'S CAUSEWAY

being a supplement

to the second volume of the

DUBLIN PENNY JOURNAL

Having in a recent number of our Journal, when describing the beauties of the county of Wicklow, the Dargle, the Waterfall, the Devil's Glen, the Meeting of the Waters, &c., promised in some future Journal to conduct the reader along the Antrim coast — lest any purchaser of the present volume might suppose we had failed in redeeming our pledge, we determined on giving, in a Supplementary Number, with the Title and Index to the Volume, a brief though faithful Guide to the Giants' Causeway, illustrated from accurate sketches, by Nichol, of several of the most striking views to be met with in the route from Belfast to that stupendous and extraordinary work of nature. That nothing can exceed in grandeur and boldness the scenery which occasionally bursts on the view of the traveller along the entire of this line, has been generally admitted by all who have travelled it. The road is hilly in the extreme, but it presents one continued scene of fine, bold, picturesque, maritime landscape ; the rocks in some places rising into precipitous cliffs, jetting headlands, noble promontories, and again, sloping down into beautiful bays and quiet harbours ; the prospect to the right being one continued sea-view, with the Scottish coast, the Isle of Arran, and other lesser islands, in the distance; that to the left pleasingly diversified with hill and valley — here a spot well cultivated, and occupied with comfortable cottages — and this again, succeeded by a barren mountain, with scarcely a cabin, even of the most miserable description, to show that it is inhabited by beings of the human kind — the entire line divided into nearly equal distances, which lie close along the coast, and which may be thus laid down — about ten miles from Belfast is the ancient town of Carrickfergus ; beyond this, about eleven miles, the town of Larne ; twelve three quarters farther on, Glenarm; twelve three quarters more, Cushendall; fifteen and a quarter, Ballycastle; and thence to the Causeway, twelve three quarter miles ; in all seventy-five miles (English measure) from Belfast. Of the inhabitants along the coast it may be sufficient to say, that although in general very superstitious, they are a well conducted, harmless people, rather well informed, intelligent, and obliging to strangers.

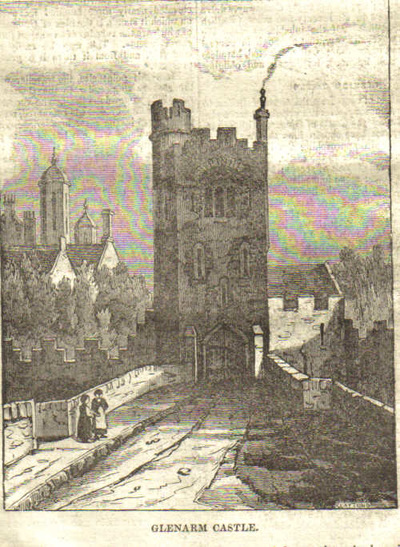

GLENARM CASTLE As the entire line of coast from the town of Belfast to the plane of the Causeway, does not present a more picturesque object than the Castle of Glenarm with its surrounding scenery, we have chosen it as the frontispiece for our volume. In approaching the little town or village, which gives its title to the castle, the road will be found very hilly, and difficult of access ; but the summit once gained, the inland scene immediately changes to one of a most interesting kind — the beautiful little village of Glenarm, containing nearly two hundred neat, whitened cottages, appears, romantically situated by the shore, in a deep ravine or sequestered glen, being closed in on either side by lofty hills, and washed by the silver waters of a mountain stream; on the opposite bank of which, in a commanding situation, stands the ancient castle, which for many years was the residence of the Antrim family. In another direction, a finely wooded glen is observed, leading to the little Deer Park, a place of singular construction, and well deserving the attention of the curious traveller. It is bounded at one side by the sea, whose waters have hollowed it into caves and archways — and at the other by a natural wall of solid basalt, rising two hundred feet high, which is as perpendicular and regular as the fortifications of a city, and presents a more impassable barrier than could possibly be raised by the hands of man. From this point there is an exceedingly fine prospect of the coast and surrounding country. — The castle is a stately, ancient pile, still bearing in its appearance something of the character of a baronial castle of the fifteenth century. The approach to it is by a lofty barbican, standing on the northern extremity of the bridge. Passing through this, a long ter¬race, overhanging the river, and confined on the opposite side by a lofty, embattled curtain-wall, leads through an avenue of ancient lime-trees, to the principal front of the building ; the appearance of which, from this approach, is very impressive. Lofty towers, terminated with cupolas and vanes, occupy the angles of the building ; the parapets are crowned with gables, decorated with carved pinnacles, and exhibiting various heraldic ornaments. — The demesne is well wooded, and rather extensive. In the cemetery connected with the church are the ruins of an ancient monastery of Franciscan friars ; but they are not of such a description as to afford matter for investigation to any traveller.

FROM GLENARM TO CUSHENDALL.

From Glenarm to Cushendall, a distance of thirteen miles is a most interesting drive. Quitting the former village, there is a fine view of the shore and coast, as far as Garron Point, distant about five miles. Passing Straid-cayle, a small fishing village but a short way from Glenarm, the widely-extended valley of Glencyle presents itself — and not far from this the village of Cairnlough.

Although the land along the entire line from Glenarm to Cushendall, is poor and (with a few exceptions) badly cultivated, yet the poorer classes do not appear to be suffering under that extreme wretchedness which is visible in some more fertile districts of the country.

From Cairnlough to Drumnasole, and thence to Garron Point, nothing can exceed the romantic beauty and variety of the scenery. On the one side of an elevated hill, in the midst of a beautiful and extensive plantation, the mansion-house of Alexander Turnley, Esq., attracts the notice of the traveller ; a short distance from this, a neat, and rather fanciful school-house, erected by that gentleman, makes its appearance ; and a little way further on, the ruins of a small ancient chapel : while on the opposite side of the road is seen the lodge of Knapan, romantically situated amid a grove of trees ; and again, but a short distance from this, and in the immediate vicinity of Garron Point, on an acute, prominent headland, elevated nearly three hundred feet above the sea-shore, on which it stands, is the rock of Dunmaul, on the summit of which are the remains of an ancient fort, having various entrenchments. This may be easily gained from the land side, and from it there is a grand and extensive prospect.

From this point also the traveller will perceive that the scenery so peculiar to the Causeway coast begins more fully to develope itself. The various strata of which the entire line of coast is composed, may now readily be traced, even by the most inexperienced in such matters.

As our limits will not permit us to give a regular or minute description of many things well worthy of observation, in travelling from this to the Causeway, we would merely observe, in a general way, that along the entire coast, of the sublime and stupendous, the wonderful and the grand, the tourist will find no deficiency ; and while there can be no question that the plane of the Causeway itself presents one of the most curious and extraordinary objects that can possibly be conceived, the varied view which meets the eye, while passing along the coast, would by many be considered as possessing much more to interest and attract admiration, than even in the structure of the pillared pavement itself. The traveller must now, however, push forward along the coast, passing through the hamlet of Waterfoot, the villages of Cushendall, Gushendun, and the small town of Ballycastle.

From Glenarm to Cushendall, a distance of thirteen miles is a most interesting drive. Quitting the former village, there is a fine view of the shore and coast, as far as Garron Point, distant about five miles. Passing Straid-cayle, a small fishing village but a short way from Glenarm, the widely-extended valley of Glencyle presents itself — and not far from this the village of Cairnlough.

Although the land along the entire line from Glenarm to Cushendall, is poor and (with a few exceptions) badly cultivated, yet the poorer classes do not appear to be suffering under that extreme wretchedness which is visible in some more fertile districts of the country.

From Cairnlough to Drumnasole, and thence to Garron Point, nothing can exceed the romantic beauty and variety of the scenery. On the one side of an elevated hill, in the midst of a beautiful and extensive plantation, the mansion-house of Alexander Turnley, Esq., attracts the notice of the traveller ; a short distance from this, a neat, and rather fanciful school-house, erected by that gentleman, makes its appearance ; and a little way further on, the ruins of a small ancient chapel : while on the opposite side of the road is seen the lodge of Knapan, romantically situated amid a grove of trees ; and again, but a short distance from this, and in the immediate vicinity of Garron Point, on an acute, prominent headland, elevated nearly three hundred feet above the sea-shore, on which it stands, is the rock of Dunmaul, on the summit of which are the remains of an ancient fort, having various entrenchments. This may be easily gained from the land side, and from it there is a grand and extensive prospect.

From this point also the traveller will perceive that the scenery so peculiar to the Causeway coast begins more fully to develope itself. The various strata of which the entire line of coast is composed, may now readily be traced, even by the most inexperienced in such matters.

As our limits will not permit us to give a regular or minute description of many things well worthy of observation, in travelling from this to the Causeway, we would merely observe, in a general way, that along the entire coast, of the sublime and stupendous, the wonderful and the grand, the tourist will find no deficiency ; and while there can be no question that the plane of the Causeway itself presents one of the most curious and extraordinary objects that can possibly be conceived, the varied view which meets the eye, while passing along the coast, would by many be considered as possessing much more to interest and attract admiration, than even in the structure of the pillared pavement itself. The traveller must now, however, push forward along the coast, passing through the hamlet of Waterfoot, the villages of Cushendall, Gushendun, and the small town of Ballycastle.

FROM CUSHENDALL TO BALLYCASTLE — TURNLEY’S ROAD — CLOGH-I-STOOKAN.

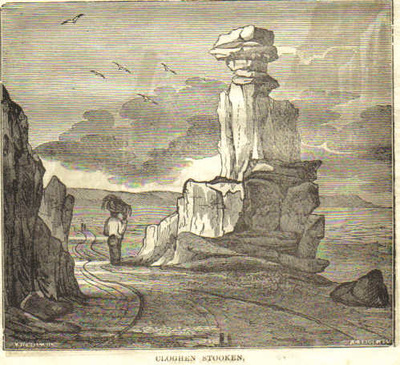

After passing Garron Point, the tourist had formerly to proceed by a road, called the Foaran Path, which from the extreme rapidity of the descent, was nearly impassable by carriages. This has some time since been remedied by Francis Turnley, Esq., to whose patriotism and liberality the traveller is indebted for an excellent road, cut at great expense and with much labour, out of the side of the mountain, along the edge of the coast — here and there immense masses of limestone being left in detached and threatening attitudes, which present an appearance quite in keeping with the general character of the entire scene. A little to the right, on the shore, an extraordinary figure is seen, called Clogh-i-Stookan, also formed of a huge limestone rock, and at one period supposed to be the most northern point of Ireland.

After passing Garron Point, the tourist had formerly to proceed by a road, called the Foaran Path, which from the extreme rapidity of the descent, was nearly impassable by carriages. This has some time since been remedied by Francis Turnley, Esq., to whose patriotism and liberality the traveller is indebted for an excellent road, cut at great expense and with much labour, out of the side of the mountain, along the edge of the coast — here and there immense masses of limestone being left in detached and threatening attitudes, which present an appearance quite in keeping with the general character of the entire scene. A little to the right, on the shore, an extraordinary figure is seen, called Clogh-i-Stookan, also formed of a huge limestone rock, and at one period supposed to be the most northern point of Ireland.

FAIRHEAD AND CARRICK-A-REDE.

To the stupendous Promontory of Benmore, or Fairhead, as it is more generally called, which lies between three and four miles from Ballycastle, and which is the most majestic headland to be seen along the entire line, the traveller must next direct his attention ; and as many persons, in their anxiety to reach the Causeway, are induced to pay but little attention to this part of the coast, it mav be well here to mention, that the basaltic area of the Causeway shore may be considered as extending from Ballycastle to Solomon's Porch at Magilligan — that portion of it denominated, par excellence, the Causeway, lying between Portrush and the western point of Bengore-head ; and whilst it must be admitted that there is much of beauty and sublimity in the various ports and promon¬tories in that division of the coast, as well as in the pillared pavement of the Causeway itself, still we incline to think, that although not frequently visited, nor much known to strangers, the precipitous facade from Ballycastle to Ballintoy, will be considered by many to be fully as beautiful, as stupendous, and as well deserving of attention as any other portion of this remarkable place. Here we have to observe, that three of the most magnificent and extraordinary objects in this range of scenery—Fairhead, Carric-a-rede, and Bengore, can only be seen to advantage from the water. The tourist may, indeed, get side-long glimpses of them from various points of land along the edge of the cliffs ; but to see them all in their beauty and sublimity, in all their grandeur and variety, they must be viewed from the water, and at a little distance. For this purpose, boats may be readily procured at Ballycastle. From this point, also, the island of Rathlin, about eight miles distant, and directly opposite, may be visited.

The promontory of Fairhead rises perpendicularly to the height of 631 feet above the level of the sea. On ap¬proaching its summit the tourist will perceive two small lakes, Lough Dhu and Lough na Cranagh — and, near to its highest point, a curious cave, said to have been a Pict's house. The view from this headland is of a most enchanting description — to the wqest, the whole line of finely variegated limestone and basaltic coast, as far as Bengore Head ; the beautiful promontory of Kenbaan or White-head majestically presenting its snow-white front to the foaming ocean — the swinging-bridge and bay of Carric-a-rede—beyond this, Sheep Inland — and directly in front, the island of Raghery ; and to the east, the Scottish coast, etc., as already described.

The promontory of Fairhead is formed of a number of basaltic colossal pillars, many of them of a much larger size than any to be seen at the Causeway — in some instances exceeding two hundred feet in length, and five in breadth, one of them forming a quadrangular prism, thirty-three feet by thirty-six on the sides, and of the gigantic altitude we have just mentioned. It is said to be the largest basaltic pillar yet discovered upon the face of our globe — exceeding in diameter the pedestal that supports the statue of Peter the Great, at Petersburgh, and consi¬derably surpassing in length the shaft of Pompey's Pillar, at Alexandria. At the foot of this magnificent colonnade is seen an immense mass of rock, similarly formed, like a wide waste of natural ruins, which are by some supposed to have been, in the course of successive age, tumbled down from their original foundation, by storms, or some more violent operation of nature — these massive bodies have sometimes withstood the shock of their fall, and often lie in groups and clumps of pillars, resembling many of the varieties of artificial ruins, and forming a very novel and striking landscape — the deep waters of the sea rolling at their base with a full and heavy swell.

To the stupendous Promontory of Benmore, or Fairhead, as it is more generally called, which lies between three and four miles from Ballycastle, and which is the most majestic headland to be seen along the entire line, the traveller must next direct his attention ; and as many persons, in their anxiety to reach the Causeway, are induced to pay but little attention to this part of the coast, it mav be well here to mention, that the basaltic area of the Causeway shore may be considered as extending from Ballycastle to Solomon's Porch at Magilligan — that portion of it denominated, par excellence, the Causeway, lying between Portrush and the western point of Bengore-head ; and whilst it must be admitted that there is much of beauty and sublimity in the various ports and promon¬tories in that division of the coast, as well as in the pillared pavement of the Causeway itself, still we incline to think, that although not frequently visited, nor much known to strangers, the precipitous facade from Ballycastle to Ballintoy, will be considered by many to be fully as beautiful, as stupendous, and as well deserving of attention as any other portion of this remarkable place. Here we have to observe, that three of the most magnificent and extraordinary objects in this range of scenery—Fairhead, Carric-a-rede, and Bengore, can only be seen to advantage from the water. The tourist may, indeed, get side-long glimpses of them from various points of land along the edge of the cliffs ; but to see them all in their beauty and sublimity, in all their grandeur and variety, they must be viewed from the water, and at a little distance. For this purpose, boats may be readily procured at Ballycastle. From this point, also, the island of Rathlin, about eight miles distant, and directly opposite, may be visited.

The promontory of Fairhead rises perpendicularly to the height of 631 feet above the level of the sea. On ap¬proaching its summit the tourist will perceive two small lakes, Lough Dhu and Lough na Cranagh — and, near to its highest point, a curious cave, said to have been a Pict's house. The view from this headland is of a most enchanting description — to the wqest, the whole line of finely variegated limestone and basaltic coast, as far as Bengore Head ; the beautiful promontory of Kenbaan or White-head majestically presenting its snow-white front to the foaming ocean — the swinging-bridge and bay of Carric-a-rede—beyond this, Sheep Inland — and directly in front, the island of Raghery ; and to the east, the Scottish coast, etc., as already described.

The promontory of Fairhead is formed of a number of basaltic colossal pillars, many of them of a much larger size than any to be seen at the Causeway — in some instances exceeding two hundred feet in length, and five in breadth, one of them forming a quadrangular prism, thirty-three feet by thirty-six on the sides, and of the gigantic altitude we have just mentioned. It is said to be the largest basaltic pillar yet discovered upon the face of our globe — exceeding in diameter the pedestal that supports the statue of Peter the Great, at Petersburgh, and consi¬derably surpassing in length the shaft of Pompey's Pillar, at Alexandria. At the foot of this magnificent colonnade is seen an immense mass of rock, similarly formed, like a wide waste of natural ruins, which are by some supposed to have been, in the course of successive age, tumbled down from their original foundation, by storms, or some more violent operation of nature — these massive bodies have sometimes withstood the shock of their fall, and often lie in groups and clumps of pillars, resembling many of the varieties of artificial ruins, and forming a very novel and striking landscape — the deep waters of the sea rolling at their base with a full and heavy swell.

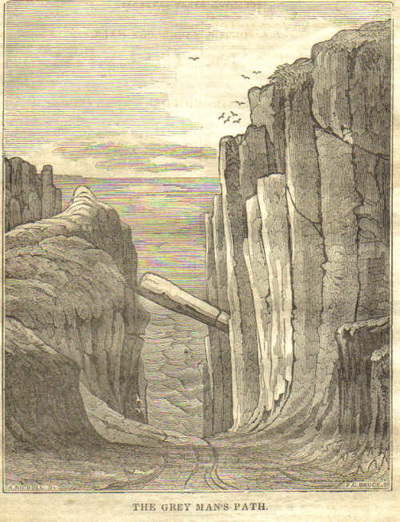

THE GREY MAN'S PATH.

The guide will now conduct the traveller to a deep and awful chasm, called " The Grey Man's Path,'' which divides this extraordinary headland into two parts, and presents a passage by which he may descend to the foot of the promontory, and take a nearer view of the astonishing and .magnificent spectacle we have just described. The chasm at the entrance to the path way is narrow, and presents a kind of natural door-way, in consequence of a massive pillar having fallen across it, and which is supported in a frightful manner, at a considerable elevation, by the rocks on either side. As the tourist descends, he will percieve that the chasm widens gradually, and the scene becomes much more interesting — a beautiful arrangement of pillars in various degrees of elevation is now apparent; the solid walls of rude and threatening columns increasing in height, regularity, and magnificence, until, at the foot of the precipice, they attain to a perpendicular elevation of 220 feet — the mighty mass upon which the promontory itself is based, and which is peculiarly characterised by savage wildness, being rendered the more imposing from the violence with which the ocean rages around it.

FORMATION OF BASALT, &C., &C,

With respect to the formation of the basalts along the Causeway coast, as well as of basalts in general, various and opposing opinions have been entertained by some of the most scientific men ; one party maintaining they were formed by the action of water, and another as strenuously contending that they owe their origin to fire, and are simply the formations of boiling lava, which at a remote period had issued from the crater of some volcano, now extinct. It would appear, however, from various experiments made, and from the most authentic evidence, that they are indebted alike to fire and water for their formation — as, in every instance where columnar trap has been moulded into forms of beauty or regularity, such as the basalts of the Causeway have assumed, it has been either situated contiguous to the ocean, or completely insulated by it, — In the immediate neighbourhood of this coast, there is an interesting and beautiful variety of fossils :—Some fine crystals have been found in Knocklead ; and the shore presents specimens of chalcedony, zeolites, belemnites, and dendrites, on which representations of several marine plants are pourtrayed with wonderful precision of figure, and some fine pebbles, tinged with various hues, which will take a high polish. Masses of mica are found in the interior—as are also detached portions of gneiss and granite. Stalactites are found in the rocks near Kenbane ; and tufa is discovered along the borders of several rills that trickle through beds of limestone.

Should the tourist determine on viewing the coast from the water, as far as Ballintoy or Bengore, the carriages or other travelling vehicles may be sent on to Bushmills, as there is nothing particularly worthy of observation along the line of road from Ballycastle to that place.— Procuring a boat at the latter place, it will be necessary, as the tide runs with great rapidity from Fairhead outside Sheep Island to Bengore, to take advantage of the flood-tide, and to keep close along the coast, in the direction of Kenbane or Whitehead, a beautiful promontory three miles and a half from Ballycastle, very lofty, composed of limestone as white as snow, and forming a narrow peninsula which runs a considerable way into the sea at right angles. Passing this point, the precipice rises to a great height, and a scene of much beauty meets the eye — the curious promontory and swinging-bridge of Carric-a-rede terminating a facade a mile in length, the greater part of which rises 360 feet above the level of the sea, the entire beautifully diversified in its formation — the pure white limestone being mixed, in regular strata, with reddish ochre and brownish basalt, and in its termination finely shaded by the dark and heavy rocks by which the immediate vicinity of Carric-a-rede is so strikingly distinguished.

Several natural caves are observed hollowed out of the rocks along this line of coast. At the foot of a precipice 280 feet high, and which, overhanging its base, forms a magnificent concave, a cavern presents itself, that may readily be entered by a boat, if the water be smooth. It is thirty-six feet in height, and about seventeen feet wide at the entrance—the sides, which are not perpendicular, but inclining inwards, being composed of neatly formed pillars, their heads being, as it were artificially, fastened into the rocks above them —and it will be seen that the roof and bottom of the cave are of a construction somewhat similar to the plane of the Causeway — the same variety of formation, nicety of fitting, and distinctness of articulation, being displayed, and the entire awakening a mingled sensation of pleasure and amazement in the beholder.

The guide will now conduct the traveller to a deep and awful chasm, called " The Grey Man's Path,'' which divides this extraordinary headland into two parts, and presents a passage by which he may descend to the foot of the promontory, and take a nearer view of the astonishing and .magnificent spectacle we have just described. The chasm at the entrance to the path way is narrow, and presents a kind of natural door-way, in consequence of a massive pillar having fallen across it, and which is supported in a frightful manner, at a considerable elevation, by the rocks on either side. As the tourist descends, he will percieve that the chasm widens gradually, and the scene becomes much more interesting — a beautiful arrangement of pillars in various degrees of elevation is now apparent; the solid walls of rude and threatening columns increasing in height, regularity, and magnificence, until, at the foot of the precipice, they attain to a perpendicular elevation of 220 feet — the mighty mass upon which the promontory itself is based, and which is peculiarly characterised by savage wildness, being rendered the more imposing from the violence with which the ocean rages around it.

FORMATION OF BASALT, &C., &C,

With respect to the formation of the basalts along the Causeway coast, as well as of basalts in general, various and opposing opinions have been entertained by some of the most scientific men ; one party maintaining they were formed by the action of water, and another as strenuously contending that they owe their origin to fire, and are simply the formations of boiling lava, which at a remote period had issued from the crater of some volcano, now extinct. It would appear, however, from various experiments made, and from the most authentic evidence, that they are indebted alike to fire and water for their formation — as, in every instance where columnar trap has been moulded into forms of beauty or regularity, such as the basalts of the Causeway have assumed, it has been either situated contiguous to the ocean, or completely insulated by it, — In the immediate neighbourhood of this coast, there is an interesting and beautiful variety of fossils :—Some fine crystals have been found in Knocklead ; and the shore presents specimens of chalcedony, zeolites, belemnites, and dendrites, on which representations of several marine plants are pourtrayed with wonderful precision of figure, and some fine pebbles, tinged with various hues, which will take a high polish. Masses of mica are found in the interior—as are also detached portions of gneiss and granite. Stalactites are found in the rocks near Kenbane ; and tufa is discovered along the borders of several rills that trickle through beds of limestone.

Should the tourist determine on viewing the coast from the water, as far as Ballintoy or Bengore, the carriages or other travelling vehicles may be sent on to Bushmills, as there is nothing particularly worthy of observation along the line of road from Ballycastle to that place.— Procuring a boat at the latter place, it will be necessary, as the tide runs with great rapidity from Fairhead outside Sheep Island to Bengore, to take advantage of the flood-tide, and to keep close along the coast, in the direction of Kenbane or Whitehead, a beautiful promontory three miles and a half from Ballycastle, very lofty, composed of limestone as white as snow, and forming a narrow peninsula which runs a considerable way into the sea at right angles. Passing this point, the precipice rises to a great height, and a scene of much beauty meets the eye — the curious promontory and swinging-bridge of Carric-a-rede terminating a facade a mile in length, the greater part of which rises 360 feet above the level of the sea, the entire beautifully diversified in its formation — the pure white limestone being mixed, in regular strata, with reddish ochre and brownish basalt, and in its termination finely shaded by the dark and heavy rocks by which the immediate vicinity of Carric-a-rede is so strikingly distinguished.

Several natural caves are observed hollowed out of the rocks along this line of coast. At the foot of a precipice 280 feet high, and which, overhanging its base, forms a magnificent concave, a cavern presents itself, that may readily be entered by a boat, if the water be smooth. It is thirty-six feet in height, and about seventeen feet wide at the entrance—the sides, which are not perpendicular, but inclining inwards, being composed of neatly formed pillars, their heads being, as it were artificially, fastened into the rocks above them —and it will be seen that the roof and bottom of the cave are of a construction somewhat similar to the plane of the Causeway — the same variety of formation, nicety of fitting, and distinctness of articulation, being displayed, and the entire awakening a mingled sensation of pleasure and amazement in the beholder.

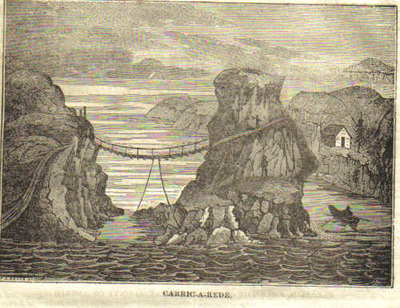

SWINGING-BRIDGE OF CARRIC-A-REDE.

Having explored this curious cavern, the dimensions of which are continued for a considerable way in, the object which next attracts attention is the swinging-bridge and island of Carric-a-rede. The headland, which projects a considerable way into the sea, and on the extremity of which there is a small cottage, built for a fishing station, is divided by a tremendous rent or chasm, supposed to have been caused by some extraordinary convulsion of nature. The chasm is sixty feet wide, the rock on either side rising about eighty feet above the level of the water. Across this mighty rent a bridge of ropes has been thrown, for the convenience of the fishermen who reside on the island during the summer months. The construction of this bridge is very simple :— Two strong ropes or cables are stretched from one chasm to another, in a parallel line, and made fast to rings fixed permanently in the rock ; across these, planks, twelve inches wide, are laid and secured ; a light rope, elevated convenient to the hand, runs parallel with the footway; and thus a bridge is formed, over which men, women, and boys, many of them carrying heavy burdens, are seen walking or running, apparently with as little concern as they would evince in advancing the same distance on terra firma. It is awful in the extreme to witness from a boat on the water, persons passing and repassing at this giddy height — and a feeling of anxiety, closely allied to pain, is invariably experienced by those who contemplate the apparently imminent danger to which poor people are exposed, while thus lightly treading the dangerous and narrow footway which conducts them across the gulph that yawns beneath their feet.

Passing under the bridge, right through the chasm, in which the water will be found much smoother, and the tide less rapid than at the outer side of the island, the tourist may proceed along the coast, through the strait which separates Sheep Island from the main land, as far as Dunseverick — or, if the weather will permit, proceeding to Bengore-head, of which there is a sublime view from the water, and from which point there is a splendid panoramic prospect of the entire line of coast on the western side of this great head-land, including Dunluce Castle and the several promontories and capes of which the Causeway is composed.

Having explored this curious cavern, the dimensions of which are continued for a considerable way in, the object which next attracts attention is the swinging-bridge and island of Carric-a-rede. The headland, which projects a considerable way into the sea, and on the extremity of which there is a small cottage, built for a fishing station, is divided by a tremendous rent or chasm, supposed to have been caused by some extraordinary convulsion of nature. The chasm is sixty feet wide, the rock on either side rising about eighty feet above the level of the water. Across this mighty rent a bridge of ropes has been thrown, for the convenience of the fishermen who reside on the island during the summer months. The construction of this bridge is very simple :— Two strong ropes or cables are stretched from one chasm to another, in a parallel line, and made fast to rings fixed permanently in the rock ; across these, planks, twelve inches wide, are laid and secured ; a light rope, elevated convenient to the hand, runs parallel with the footway; and thus a bridge is formed, over which men, women, and boys, many of them carrying heavy burdens, are seen walking or running, apparently with as little concern as they would evince in advancing the same distance on terra firma. It is awful in the extreme to witness from a boat on the water, persons passing and repassing at this giddy height — and a feeling of anxiety, closely allied to pain, is invariably experienced by those who contemplate the apparently imminent danger to which poor people are exposed, while thus lightly treading the dangerous and narrow footway which conducts them across the gulph that yawns beneath their feet.

Passing under the bridge, right through the chasm, in which the water will be found much smoother, and the tide less rapid than at the outer side of the island, the tourist may proceed along the coast, through the strait which separates Sheep Island from the main land, as far as Dunseverick — or, if the weather will permit, proceeding to Bengore-head, of which there is a sublime view from the water, and from which point there is a splendid panoramic prospect of the entire line of coast on the western side of this great head-land, including Dunluce Castle and the several promontories and capes of which the Causeway is composed.

THE ISLAND OF RATHLIN OR RAGHERY.

The island of Rathlin or Raghery, lies about seven miles and a half from the shore, is rather more than six miles in length, arid one in breadth, measuring two thousand plantation acres, and containing about eleven hundred inhabitants, who are almost all occupied in agricultural pursuits, and the making of kelp from the sea weed found on the rock of which the island is composed. The people are simple, laborious, and honest, and possess a degree of affection for the island, that may very much surprise a stranger. In conversation, they always talk of Ireland as a foreign kingdom, and really have scarcely any intercourse with it, except in the way of their little trade. Small as this spot is, one can nevertheless trace two different characters among its inhabitants. The Kenramer, or western end, is craggy and mountainous, the land in the valleys is rich and well cultivated, but the coast destitute of harbours. A single native is here known to fix his rope to a stake driven into the summit of a precipice, and from thence, alone, and unassisted, to swing down the face of a rock in quest of the nests of sea-fowl. From hence, activity, bodily strength, and self dependence, are, eminent among the Kenramer men. — Want of intercourse with strangers has preserved many peculiarities, and their native Irish still continues to be the universal language. The Ushet end, on the contrary, is barren in its soil, but more open, and well supplied with little harbours ; hence, its inhabitants are become fishermen, and are accustomed to make short voyages and to barter. Intercourse with strangers has rubbed off many of their peculiarities, and the English tongue is well un¬derstood, and generally spoken by them. Near Ushet is a lake of fresh water, upwards of a mile in circumference — one hundred and forty four feet above the level of the sea.

There is also another lake in the opposite end of the island, called Cligan, two hundred and thirty-eight feet above the level of the sea. The highest hill is called Ken Truan, it is four hundred and forty four feet high. Near Ushet is Doon Point, remarkable for its resemblance to the Causeway ; its pillars have commonly five, six, or seven sides.

CAVE OF PORTCOON.

Although to those who may have kept close to the shore by Dunseverick Castle, there would be rather a saving of time in at once proceeding to view the magnificent scenery from the summit of the cliffs, and afterwards descending to the Causeway from the Rock-heads, by the Stookans, we would rather advise that the course usually pursued should be taken — that the cave of Portcoon be visited, the great mole of the Causeway next examined, and then ascending the mountain steep by a path which winds around Port Noffer, the numerous capes and promontories which form the back ground of the Causeway, may be leisurely examined from the edge of the cliffs.

Following the guide, with cautious steps, round a projecting point of rock, the cave of Portcoon will now be entered by the land side. It is a cavern of very considerable dimensions, hollowed out of the solid rock, and assuming in its shape something of the form of a pointed arch. Into this the sea rushes, even in the calmest weather, with a bold and boisterous swell ; but when the sea is agitated by a storm, the tremendous roaring of the waters, as they break into the entrance, is terrific in the extreme. The sides and roof are formed, or at least coated, with a number of stones of various shapes and sizes, partly rounded off, as if by the action of the waves, and embedded in a kind of basaltic paste or cement. The echo produced by the beating of the billows, as they enter the cavern, is very great, while the reverberations succeeding the report of a pistol, generally fired off by the guide, are of a very extraordinary description, much resembling the rolling of several peals of thunder near at hand. When the day is fine, the scene presented here is peculiarly grand and interesting ; the irregular basaltic side-walls, with the dark shading of the deeper recesses of the cavern, upon which the foam-crested wave spends its last dying murmurings, forming a fine contrast to the freshness and brilliancy observable outside.

The island of Rathlin or Raghery, lies about seven miles and a half from the shore, is rather more than six miles in length, arid one in breadth, measuring two thousand plantation acres, and containing about eleven hundred inhabitants, who are almost all occupied in agricultural pursuits, and the making of kelp from the sea weed found on the rock of which the island is composed. The people are simple, laborious, and honest, and possess a degree of affection for the island, that may very much surprise a stranger. In conversation, they always talk of Ireland as a foreign kingdom, and really have scarcely any intercourse with it, except in the way of their little trade. Small as this spot is, one can nevertheless trace two different characters among its inhabitants. The Kenramer, or western end, is craggy and mountainous, the land in the valleys is rich and well cultivated, but the coast destitute of harbours. A single native is here known to fix his rope to a stake driven into the summit of a precipice, and from thence, alone, and unassisted, to swing down the face of a rock in quest of the nests of sea-fowl. From hence, activity, bodily strength, and self dependence, are, eminent among the Kenramer men. — Want of intercourse with strangers has preserved many peculiarities, and their native Irish still continues to be the universal language. The Ushet end, on the contrary, is barren in its soil, but more open, and well supplied with little harbours ; hence, its inhabitants are become fishermen, and are accustomed to make short voyages and to barter. Intercourse with strangers has rubbed off many of their peculiarities, and the English tongue is well un¬derstood, and generally spoken by them. Near Ushet is a lake of fresh water, upwards of a mile in circumference — one hundred and forty four feet above the level of the sea.

There is also another lake in the opposite end of the island, called Cligan, two hundred and thirty-eight feet above the level of the sea. The highest hill is called Ken Truan, it is four hundred and forty four feet high. Near Ushet is Doon Point, remarkable for its resemblance to the Causeway ; its pillars have commonly five, six, or seven sides.

CAVE OF PORTCOON.

Although to those who may have kept close to the shore by Dunseverick Castle, there would be rather a saving of time in at once proceeding to view the magnificent scenery from the summit of the cliffs, and afterwards descending to the Causeway from the Rock-heads, by the Stookans, we would rather advise that the course usually pursued should be taken — that the cave of Portcoon be visited, the great mole of the Causeway next examined, and then ascending the mountain steep by a path which winds around Port Noffer, the numerous capes and promontories which form the back ground of the Causeway, may be leisurely examined from the edge of the cliffs.

Following the guide, with cautious steps, round a projecting point of rock, the cave of Portcoon will now be entered by the land side. It is a cavern of very considerable dimensions, hollowed out of the solid rock, and assuming in its shape something of the form of a pointed arch. Into this the sea rushes, even in the calmest weather, with a bold and boisterous swell ; but when the sea is agitated by a storm, the tremendous roaring of the waters, as they break into the entrance, is terrific in the extreme. The sides and roof are formed, or at least coated, with a number of stones of various shapes and sizes, partly rounded off, as if by the action of the waves, and embedded in a kind of basaltic paste or cement. The echo produced by the beating of the billows, as they enter the cavern, is very great, while the reverberations succeeding the report of a pistol, generally fired off by the guide, are of a very extraordinary description, much resembling the rolling of several peals of thunder near at hand. When the day is fine, the scene presented here is peculiarly grand and interesting ; the irregular basaltic side-walls, with the dark shading of the deeper recesses of the cavern, upon which the foam-crested wave spends its last dying murmurings, forming a fine contrast to the freshness and brilliancy observable outside.

THE CAUSEWAY.

Having regained the Rock-heads, at a little distance to the right, the guide will point out the path which conducts to the Causeway, and which was cut at very considerable expense by the Earl of Bristol, Bishop cf Derry. From the little hills, popularly denominated the Stookans, the first view of the Causeway is obtained; and a more sub¬lime, imposing, and beautiful scene could not by any possibility be imagined by the most enthusiastic mind, than that which bursts on the sight — an immense and magnificent bay, indented by a number of capes and headlands, which rise around from a height of three hundred and fifty to four hundred feet above the level of the sea, presenting at all points a variety of the most magnificent and interesting views — as if nature and art had united their energies to form one truly grand and splendid picture. Here a beautiful colonnade of the most perfectly formed massive pillars, finely relieved by the dark basaltic cliff into which they appear inserted, or as standing out in bold and prominent relief ; this again succeeded by numerous distinct groups and ranges in the columnar form, assuming a variety of shapes and sizes ; in another direction the dark sides of the mighty cliff rising up like the walls of some vast edifice, here and there broken down ; while, at their base, appears the ponderous wreck of numerous rocks and columns; flung from their original position, and lying in wild disorder—the entire scene forcing upon the beholder the idea that he is contemplating the remains of some mighty fabric, hurled into desolation by a tremendous earthquake, or some other equally terrible convulsion of nature. But it is not the immensity or the grandeur of the scene which will alone fix the attention here ; the eye now turns to an object equally interesting, and even more curious than any which has yet been surveyed. From the base of this stupendous facade, a mole or quay, some hundred feet wide, of exquisitely shaped pillars, is observed to project, gradually diminishing from a height of two hundred feet, until, at a distance of six hundred feet, it is lost in the sea. This platform or mole may be described as forming one immense inclined plane, divided into three compartments by two of those great whindykes to which we have before alluded, as sloping gradually down from the base of the headland, and running into the sea between Port-na-Gange and Port Noffer, to an extent which has never yet been ascertained. The divisions are distinguished by the names of the Grand Causeway, the Middle Causeway, and the Little Causeway ; the first mentioned extending sir hundred feet at low water, while the last does not exceed four hundred feet — the entire composed of a number of pillars of different shapes, and varying from fifteen to twenty-six inches in diameter, sunk in the earth or the surrounding rock, and standing nearly perpendicular — those nearest the cliff having a slight inclination to the west, while those closer to the sea take a contrary direction; their perfectly denuded heads presenting a beautiful polygonal pavement, somewhat resembling a honey-comb or wasp's nest, over which the traveller treads with security ; for although each is in itself a perfect pillar, they are all so completely fitted together, and so nicely joined, that the water which falls upon them will not penetrate between them. They are irregular prisms, and display the greatest variety of figure, being septagonal, pentagonal, and hexagonal ; a few having eight sides, and some others four; three have been discovered with nine sides, while only one has yet been found with but three. Scarcely any one of them will be found to be equilateral, to have sides and angles of the same dimensions, or to correspond exactly in form or size with one another ; while, at the same time, the sum of all the angles of any one of them will be found to be equal to four right angles — the sides of one corresponding exactly to those of the others which lie next to it, although otherwise differing completely in size and form.

In the entire Causeway it is computed there are from thirty to forty thousand pillars — the tallest measuring about thirty-three feet. On the eastern side a pillar will be pointed out with thirty-eight joints, and it is said that two others have been broken off.

The guide will now direct the attention of the traveller to matters of minor curiosity ; — the Giant's Well, a tiny spring of pure fresh water, forcing its way up between the joints of two of the columns— his Chair, Bag-pipes, and various other little et ceteras belonging to the renowned hero of the Causeway. Turning from these to still more magnificent objects, the eye will naturally rest upon the Giant's Theatre and the Giant's Organ, the latter a beautiful colonnade of pillars, one hundred and twenty feet long—so called from the resemblance it bears to the pipes of an organ. Opposite to these is the Giant's Loom ; while a little further to the east, several isolated columns are seen standing apart from the rest, which are popularly called the Chimney-tops, from the likeness they bear at a distance to the chimneys of a castle. The extraordinary stratified construction of the cliffs all around will, no doubt, also fix the attention of every curious observer.

The tourist having examined every object of interest which can be viewed from the foot of the great cliff or promontory, the guide will next point to a steep and narrow path that leads up the nearly perpendicular acclivity which forms the back-ground of Port Noffer.

ANECDOTES OF PERSON'S FALLING FROM THE CLIFFS.

The guides relate several interesting stories of individuals, who fell from the heights in this neighbourhood. — From the Aird Snout, a man named J. Kane tumbled down while engaged in searching for fossil-coal, during a severe winter — and, strange to say, was taken up alive, although seriously injured by the fall. Another man, named Adam Morning, when descending a giddy path that leads to the foot of Port-na-Spania, with his wife's breakfast, who was at the time employed in making kelp, missed his footing, and tumbling headlong, was dashed to atoms ere he reached the bottom. The poor woman witnessed the misfortune from a distance ; but supposing, from the kind of coat he wore, that it had been one of the sheep that had been grazing on the headland, she went to examine it, when she found instead, the mangled corpse of her husband. Another story is told of a poor girl, who, being betrothed to one she loved, in order to furnish herself and her intended husband with some of the little comforts of life, procured employment on the shore, in the manufacture alluded to, with some other persons in the neighbourhood. Port-na-Spania, as will be observed, is completely surrounded by a tremendous precipice, from three to four hundred feet high, and is only accessible by a narrow pathway, by far the most difficult and dangerous of any of those nearly perpendicular ascents to be met with along the entire coast. — Up this frightful footway was this poor girl, in common with all who were engaged in the same manufacture, obliged to climb, heavily laden with a burden of the kelp ; and having gained the steepest point of the peak, was just about to place her foot on the summit, when, in consequence of the load on her shoulders shifting a little to one side, she lost her balance, fell backwards, and ere she reached the bottom, was a lifeless and a mangled corpse. To behold women and children toiling up this dreadful ascent, bearing heavy loads, either on their heads or fastened from their necks and shoulders, is really painful, even to the least sensitive, unaccustomed to the sight — and yet the natives themselves appear to think no¬thing whatever of it.

An anecdote is also related of a man who was in the habit of seating himself on the edge of a cliff which overhung its base, at Poortmoor, to enjoy the beauty of the widely extended scene. One fine summer morning, however, having gained the height, and taken his accustomed seat, while indulging in the thoughts and feelings which we may suppose the scene and situation likely to inspire, " a change came o'er the spirit of his dream," — the rock upon which he was perched gave way, and, in the twinkling of an eye, bore him on " its rapid wing" to the foot of a precipice, where it sunk several feet into the earth — safely depositing its ambitious bestrider on the shore, at a distance of fully four hundred feet from the towering eminence off which he had made his involuntary aerial descent.

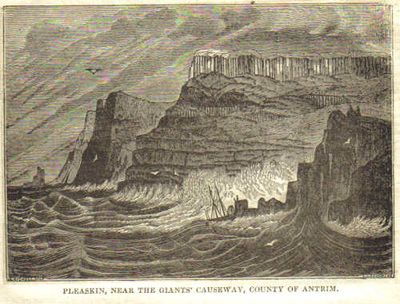

PLEASKIN.

Towards the head-land of Bengore, the tourist may now proceed, following the windings of the cliffs, and examining in succession the various capes and bays into which the great promontory is broken. While the appearance of this entire line, from port Noffer to Bengore-head, must be admitted to be grand in the extreme, the promontory of Pleaskin will be found more particularly deserving of minute attention. It is a continuation of the headland of Bengore ; and is beyond doubt the prettiest thing in nature, in the way of a promontory. It appears as though it had been painted for effect, in various shades of green, vermillion rock, red ochre, grey lichens, &c. — its general form so beautiful — its storied pillars, tier over tier, so architecturally graceful — its curious and varied stratifications supporting the columnar ranges — here the dark brown amorphous basalt — there the red ochre, and below that again the slender but distinct lines of wood-coal — all the edges of its different stratifications tastefully varied by the hand of vegetable nature, with grasses and ferns, and rock-plants ; — in the various strata of which it is composed, sublimity and beauty having been blended together in the most extraordinary manner.

BENGORE HEAD. Bengore, or the Goat's Promontory, which rises three hundred and thirty feet above the water, is the extreme headland ; but there is nothing in the scenery by which it is surrounded particularly worthy of observation, with the exception of a curious stratum of fossil-coal, which is found lying between two ranges of basaltic pillars — and the exceedingly fine view which meets the eye from its summit in the direction of Fairhead, Rathlin, &c.

DUNLUCE CASTLE.

Having viewed every thing worthy of notice in the immediate direction of the Causeway, the traveller may proceed towards Dunluce Castle, on his route to Coleraine. The Castle, which our readers will find described in a former number of our Journal, is one of the finest ruins to be met with in Ireland, and possesses very considerable interest, as having been connected with several important events in the history of the country.

* “Oral history states, that “in olden time” all the rents of Ireland were paid at this place, and that the last Danish invaders embarked from here”

*** From our limited space the directions and descriptions we have given of this interesting line of coast have necessarily been very concise ; we would, therefore, refer the traveller who may wish for further information, to “The Northern Tourist," published by Messrs. Curry, and Co. and from which (although the copyright is now altogether their own,) they have kindly permitted us to make such extracts as suited our purpose. " The Guide to the Causeway," which they have just published, we would particularly recommend to the notice of persons travelling in the north of Ireland, as affording a correct picture of that extraordinary work of nature. Having now conducted the reader along the most interesting portions of the Antrim coast, pointing out in our way whatever we considered might interest or amuse, we take our leave, in the hope of again meeting him in the course of the ensuing year, in some other interesting portions of our country heretofore undescribed.

Having regained the Rock-heads, at a little distance to the right, the guide will point out the path which conducts to the Causeway, and which was cut at very considerable expense by the Earl of Bristol, Bishop cf Derry. From the little hills, popularly denominated the Stookans, the first view of the Causeway is obtained; and a more sub¬lime, imposing, and beautiful scene could not by any possibility be imagined by the most enthusiastic mind, than that which bursts on the sight — an immense and magnificent bay, indented by a number of capes and headlands, which rise around from a height of three hundred and fifty to four hundred feet above the level of the sea, presenting at all points a variety of the most magnificent and interesting views — as if nature and art had united their energies to form one truly grand and splendid picture. Here a beautiful colonnade of the most perfectly formed massive pillars, finely relieved by the dark basaltic cliff into which they appear inserted, or as standing out in bold and prominent relief ; this again succeeded by numerous distinct groups and ranges in the columnar form, assuming a variety of shapes and sizes ; in another direction the dark sides of the mighty cliff rising up like the walls of some vast edifice, here and there broken down ; while, at their base, appears the ponderous wreck of numerous rocks and columns; flung from their original position, and lying in wild disorder—the entire scene forcing upon the beholder the idea that he is contemplating the remains of some mighty fabric, hurled into desolation by a tremendous earthquake, or some other equally terrible convulsion of nature. But it is not the immensity or the grandeur of the scene which will alone fix the attention here ; the eye now turns to an object equally interesting, and even more curious than any which has yet been surveyed. From the base of this stupendous facade, a mole or quay, some hundred feet wide, of exquisitely shaped pillars, is observed to project, gradually diminishing from a height of two hundred feet, until, at a distance of six hundred feet, it is lost in the sea. This platform or mole may be described as forming one immense inclined plane, divided into three compartments by two of those great whindykes to which we have before alluded, as sloping gradually down from the base of the headland, and running into the sea between Port-na-Gange and Port Noffer, to an extent which has never yet been ascertained. The divisions are distinguished by the names of the Grand Causeway, the Middle Causeway, and the Little Causeway ; the first mentioned extending sir hundred feet at low water, while the last does not exceed four hundred feet — the entire composed of a number of pillars of different shapes, and varying from fifteen to twenty-six inches in diameter, sunk in the earth or the surrounding rock, and standing nearly perpendicular — those nearest the cliff having a slight inclination to the west, while those closer to the sea take a contrary direction; their perfectly denuded heads presenting a beautiful polygonal pavement, somewhat resembling a honey-comb or wasp's nest, over which the traveller treads with security ; for although each is in itself a perfect pillar, they are all so completely fitted together, and so nicely joined, that the water which falls upon them will not penetrate between them. They are irregular prisms, and display the greatest variety of figure, being septagonal, pentagonal, and hexagonal ; a few having eight sides, and some others four; three have been discovered with nine sides, while only one has yet been found with but three. Scarcely any one of them will be found to be equilateral, to have sides and angles of the same dimensions, or to correspond exactly in form or size with one another ; while, at the same time, the sum of all the angles of any one of them will be found to be equal to four right angles — the sides of one corresponding exactly to those of the others which lie next to it, although otherwise differing completely in size and form.

In the entire Causeway it is computed there are from thirty to forty thousand pillars — the tallest measuring about thirty-three feet. On the eastern side a pillar will be pointed out with thirty-eight joints, and it is said that two others have been broken off.

The guide will now direct the attention of the traveller to matters of minor curiosity ; — the Giant's Well, a tiny spring of pure fresh water, forcing its way up between the joints of two of the columns— his Chair, Bag-pipes, and various other little et ceteras belonging to the renowned hero of the Causeway. Turning from these to still more magnificent objects, the eye will naturally rest upon the Giant's Theatre and the Giant's Organ, the latter a beautiful colonnade of pillars, one hundred and twenty feet long—so called from the resemblance it bears to the pipes of an organ. Opposite to these is the Giant's Loom ; while a little further to the east, several isolated columns are seen standing apart from the rest, which are popularly called the Chimney-tops, from the likeness they bear at a distance to the chimneys of a castle. The extraordinary stratified construction of the cliffs all around will, no doubt, also fix the attention of every curious observer.

The tourist having examined every object of interest which can be viewed from the foot of the great cliff or promontory, the guide will next point to a steep and narrow path that leads up the nearly perpendicular acclivity which forms the back-ground of Port Noffer.

ANECDOTES OF PERSON'S FALLING FROM THE CLIFFS.

The guides relate several interesting stories of individuals, who fell from the heights in this neighbourhood. — From the Aird Snout, a man named J. Kane tumbled down while engaged in searching for fossil-coal, during a severe winter — and, strange to say, was taken up alive, although seriously injured by the fall. Another man, named Adam Morning, when descending a giddy path that leads to the foot of Port-na-Spania, with his wife's breakfast, who was at the time employed in making kelp, missed his footing, and tumbling headlong, was dashed to atoms ere he reached the bottom. The poor woman witnessed the misfortune from a distance ; but supposing, from the kind of coat he wore, that it had been one of the sheep that had been grazing on the headland, she went to examine it, when she found instead, the mangled corpse of her husband. Another story is told of a poor girl, who, being betrothed to one she loved, in order to furnish herself and her intended husband with some of the little comforts of life, procured employment on the shore, in the manufacture alluded to, with some other persons in the neighbourhood. Port-na-Spania, as will be observed, is completely surrounded by a tremendous precipice, from three to four hundred feet high, and is only accessible by a narrow pathway, by far the most difficult and dangerous of any of those nearly perpendicular ascents to be met with along the entire coast. — Up this frightful footway was this poor girl, in common with all who were engaged in the same manufacture, obliged to climb, heavily laden with a burden of the kelp ; and having gained the steepest point of the peak, was just about to place her foot on the summit, when, in consequence of the load on her shoulders shifting a little to one side, she lost her balance, fell backwards, and ere she reached the bottom, was a lifeless and a mangled corpse. To behold women and children toiling up this dreadful ascent, bearing heavy loads, either on their heads or fastened from their necks and shoulders, is really painful, even to the least sensitive, unaccustomed to the sight — and yet the natives themselves appear to think no¬thing whatever of it.

An anecdote is also related of a man who was in the habit of seating himself on the edge of a cliff which overhung its base, at Poortmoor, to enjoy the beauty of the widely extended scene. One fine summer morning, however, having gained the height, and taken his accustomed seat, while indulging in the thoughts and feelings which we may suppose the scene and situation likely to inspire, " a change came o'er the spirit of his dream," — the rock upon which he was perched gave way, and, in the twinkling of an eye, bore him on " its rapid wing" to the foot of a precipice, where it sunk several feet into the earth — safely depositing its ambitious bestrider on the shore, at a distance of fully four hundred feet from the towering eminence off which he had made his involuntary aerial descent.

PLEASKIN.

Towards the head-land of Bengore, the tourist may now proceed, following the windings of the cliffs, and examining in succession the various capes and bays into which the great promontory is broken. While the appearance of this entire line, from port Noffer to Bengore-head, must be admitted to be grand in the extreme, the promontory of Pleaskin will be found more particularly deserving of minute attention. It is a continuation of the headland of Bengore ; and is beyond doubt the prettiest thing in nature, in the way of a promontory. It appears as though it had been painted for effect, in various shades of green, vermillion rock, red ochre, grey lichens, &c. — its general form so beautiful — its storied pillars, tier over tier, so architecturally graceful — its curious and varied stratifications supporting the columnar ranges — here the dark brown amorphous basalt — there the red ochre, and below that again the slender but distinct lines of wood-coal — all the edges of its different stratifications tastefully varied by the hand of vegetable nature, with grasses and ferns, and rock-plants ; — in the various strata of which it is composed, sublimity and beauty having been blended together in the most extraordinary manner.

BENGORE HEAD. Bengore, or the Goat's Promontory, which rises three hundred and thirty feet above the water, is the extreme headland ; but there is nothing in the scenery by which it is surrounded particularly worthy of observation, with the exception of a curious stratum of fossil-coal, which is found lying between two ranges of basaltic pillars — and the exceedingly fine view which meets the eye from its summit in the direction of Fairhead, Rathlin, &c.

DUNLUCE CASTLE.

Having viewed every thing worthy of notice in the immediate direction of the Causeway, the traveller may proceed towards Dunluce Castle, on his route to Coleraine. The Castle, which our readers will find described in a former number of our Journal, is one of the finest ruins to be met with in Ireland, and possesses very considerable interest, as having been connected with several important events in the history of the country.

* “Oral history states, that “in olden time” all the rents of Ireland were paid at this place, and that the last Danish invaders embarked from here”

*** From our limited space the directions and descriptions we have given of this interesting line of coast have necessarily been very concise ; we would, therefore, refer the traveller who may wish for further information, to “The Northern Tourist," published by Messrs. Curry, and Co. and from which (although the copyright is now altogether their own,) they have kindly permitted us to make such extracts as suited our purpose. " The Guide to the Causeway," which they have just published, we would particularly recommend to the notice of persons travelling in the north of Ireland, as affording a correct picture of that extraordinary work of nature. Having now conducted the reader along the most interesting portions of the Antrim coast, pointing out in our way whatever we considered might interest or amuse, we take our leave, in the hope of again meeting him in the course of the ensuing year, in some other interesting portions of our country heretofore undescribed.