THERE is something very attractive about any narrow gauge railway system. While one may admire, and perhaps be a little awed by a giant engine of standard gauge, a smaller edition is in many ways still more interesting to a railway enthusiast, who can crawl all round, and perhaps even drive the miniature. It matters little whether the particular line uses scale models of full-sized engines, as on the Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway, or genuine narrow-gauge locomotives built strictly for utility and without any particular eye to their publicity value. Scale models are almost entirely confined to 15-inch gauge lines, but there is within the British Isles a considerable number of light railways having gauges in the neighbourhood of three feet, on which are to be found some very interesting locomotive types.

The west of Ireland was at one time served by quite a number of such lines. A cheap type of construction can be used that is naturally attractive to the promoters of a railway planned to serve a thinly populated region where there is little chance of any heavy traffic; but in recent years most of these lines have suffered severely from road competition, train services have been reduced to a mere skeleton of their former selves, and the majority of the passenger workings have been operated by Diesel railcars. The Northern Counties Committee section of the L.M.S. however has, in the Ballycastle branch, one narrow-gauge section over which a full passenger service is still worked entirely by steam locomotives, and a more fascinating little railway it would be hard to imagine.

This branch connects at Ballymoney with the broad gauge main line from Belfast to Portrush and Londonderry; like that of the other N.C.C. non-standard routes the gauge is 3 ft. Although the branch is only 16 1/4 miles long it is an important link, and provides the quickest service to one of the most charming resorts on the Antrim coast. For a long time it was an absolutely independent concern, long after the neighbouring narrow gauge lines, the Ballymena and Larne, and the Ballymena, Cushendall and Red Bay, had been absorbed in the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway, the Ballycastle line stood out alone, and it was nearly two years after the English Midland Railway, and with it of course the N.C.C., had become part of the L.M.S, that the separate existence of the company came to an end.

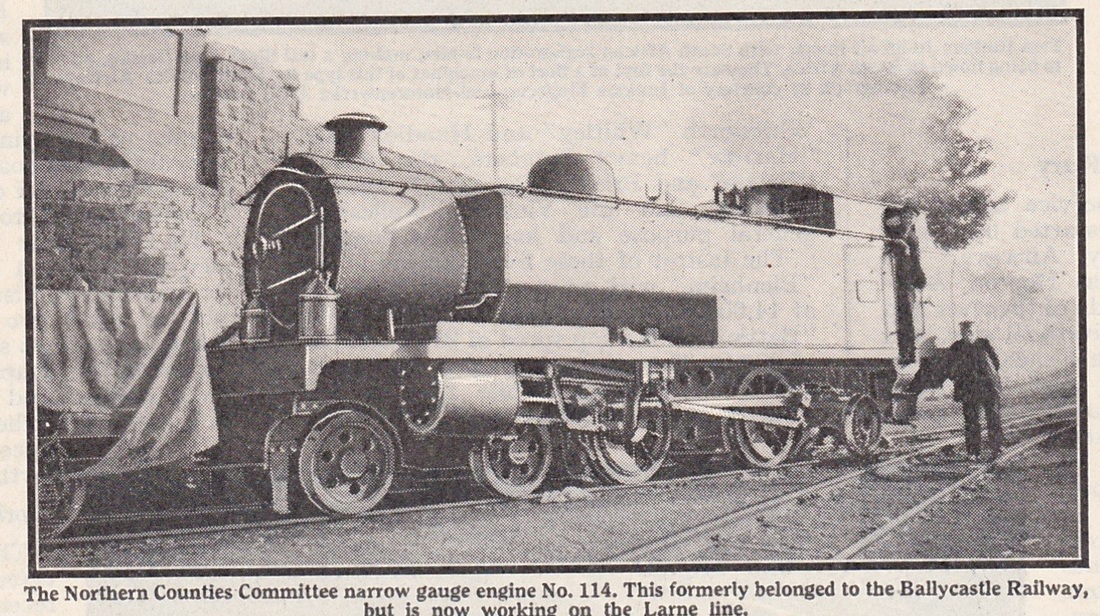

Until that time traffic had been operated almost entirely by two 4-4-2 tank engines built by Kitson and Co. in 1908. They are portly looking engines of characteristic Kitson appearance, but after the amalgamation they were transferred to Ballymena to work goods trains on the Larne line. Their place on the Ballycastle Railway was at first taken by some of the 0-4-0 tank locomotives previously used on the Larne line; by their very size and quaintness these latter were irresistibly fascinating little engines, but all of them are now scrapped. When the passenger service was withdrawn on the Larne and Cushendall branches considerably fewer narrow gauge engines were needed for the whole system, and it was naturally the oldest and smallest that went to the wall.

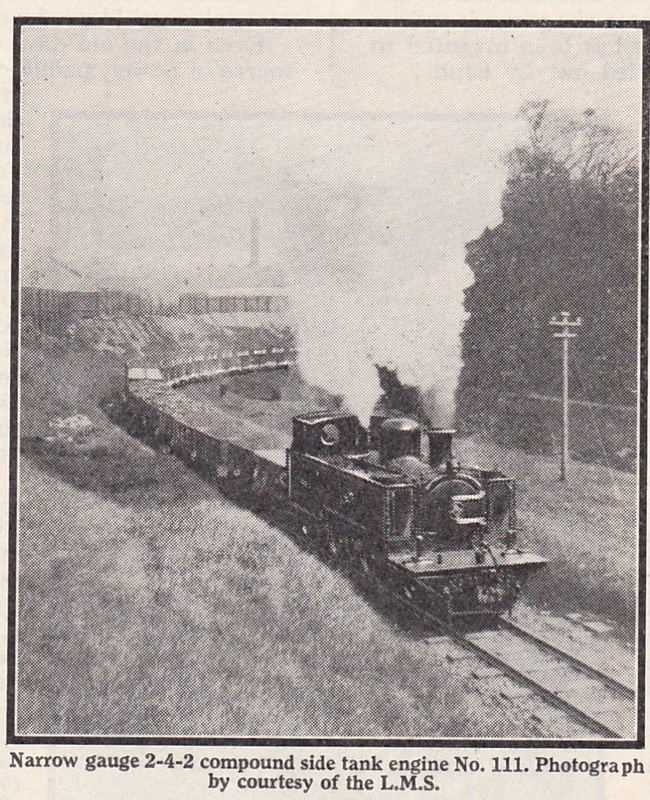

The Ballycastle line is now being worked by two of the Class S 2-4-2 compounds, which are among the most distinctive and original tank locomotive designs that have ever been put on the road. In the "M.M." for September 1936 I described the remarkable two-cylinder compounds designed by Mr. Bowman Malcolm for the broad gauge line of the N.C.C.; in applying the Worsdell-von Borries system to the narrow gauge both cylinders had to be placed outside owing to the very restricted space between the frames. There was nothing unusual in the mere fact of the cylinders being outside, for all the other narrow gauge engines were the same in this respect; what makes the compounds look so queer when seen from the front end is that the cylinders are of different sizes. The high-pressure cylinder is 14 3/4 in. diameter, and the low-pressure 21 in. diameter, both having a stroke of 20 in.

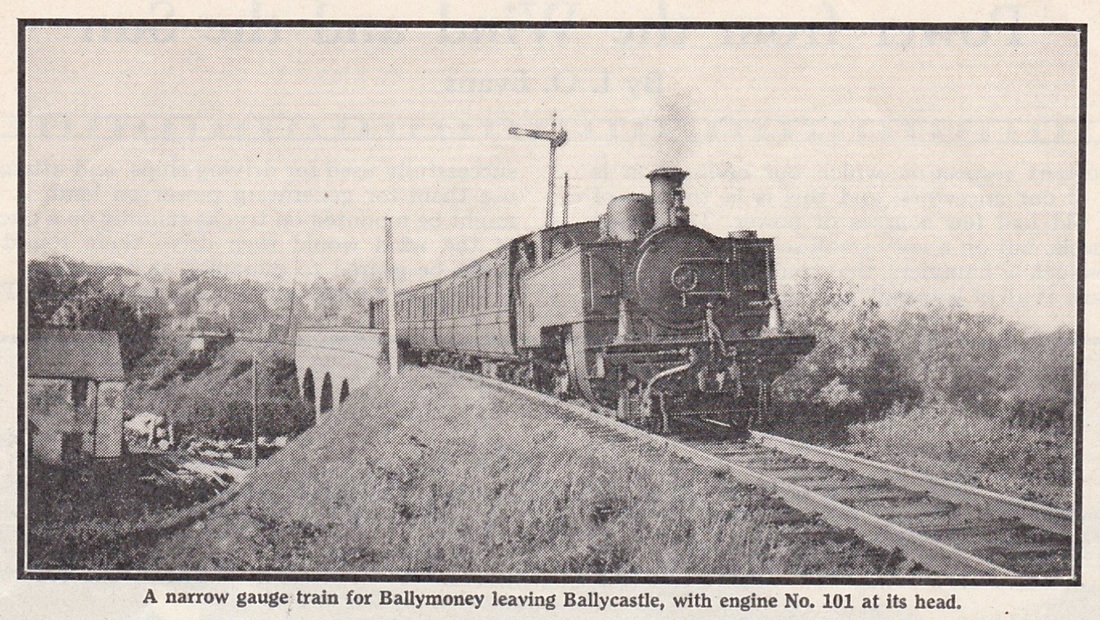

The engines were originally designed to work on the Ballymena and Larne line, over which a boat express used to be run in connection with the Stranraer steamer. This train was timed quite fast for a narrow gauge line, and the stiff ascent to Ballynashee summit involved some strenuous locomotive work. In view of this duty they were provided with side tanks of large capacity. The first two of these engines were built by Beyer Peacock in 1892; two further engines were added to the stock in 1908-9, and it is these two that are now working on the Ballycastle line, namely Nos. 101 and 102. The last two of the type were constructed as recently as 1919-20. One of the 1892 engines, No. 110, has recently been rebuilt with a Belpaire boiler having 200 lb. per sq. in. pressures, and this alteration and the consequent increase in weight have necessitated its conversion to the 2-4-4 wheel arrangement. All these narrow gauge engines are painted Midland red, and look very fine. The two original 2-4-2 engines were painted in the bright myrtle-green livery of the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway. They were lined out in white and red in a manner very similar to that of the former L.N.W.R., and the likeness was heightened by the cast number plates, having raised figures on a bright orange ground. After the Midland took over, all the Northern Counties engines were painted a pleasing shade of olive-grey, known officially as "invisible green."

Coming now to the Ballycastle line itself, the track layout at Ballymoney is quite complicated. Narrow gauge passenger trains are accommodated alongside the up main line platform, but there is an extensive broad gauge goods yard on the up side for dealing with the large cattle traffic. Not only this, but by running broad and narrow gauge goods lines alongside each other the transhipment of merchandise for the Ballycastle branch is made much easier. The presence of this big goods yard however means that broad gauge shunting, and goods movements to and from the main line, are carried out right across the narrow gauge tracks; accordingly the points and signals of both gauges are all interlocked with one another just as though they were part of the same system. The narrow gauge signals have miniature arms carried much lower than the usual height. Once clear of Ballymoney yard signalling presents no difficulties, for the branch is worked on the "one engine in steam" principle. The two locomotives shedded at Ballycastle are used on alternate days, one being sufficient to work the whole day's service. The branch possesses only two engine crews; whichever locomotive is doing the day's work is remanned in the early afternoon, the two pairs of men working "early" and "late" turn on alternate weeks.

Once a traveller alights from the main line train at Ballymoney and goes over to the branch platform, all the traditional bustle and efficiency of the N.C.C. system is gone in a flash, or so it seems. Here is the perfect Irish joke of a railway. Passengers join in lively badinage with enginemen and guard, the fireman is solemnly recoaling the engine from wicker baskets, and a stranger feels as though he has dropped in at some intimate family party rather than a serious transportation concern. But this homely happy-go-lucky sort of atmosphere reflects anything but the true character of the line, which despite outward appearances is just as efficient and reliable as any other part of the N.C.C., which, renowned as it is for strict punctuality, is saying a great deal.

The somewhat primitive method of refuelling the narrow gauge engines at Ballymoney is of course due to the absence of any form of mechanical coaling appliance. All coal used on the N.C.C. is imported from Scotland, and supplies for the Ballycastle line are sent down from Belfast and transferred at Ballymoney into small baskets so as to be easily handled by the local firemen. The engines are watered from a picturesquely old-fashioned tank built up on brick pillars on the extreme far side of Ballymoney goods yard, and in consequence on each trip locomotives have to make quite a number of reversing movement in order to replenish their tanks. To a stranger preparing, according to his nature, either to enjoy or bemoan the joke; the carriage interiors provide the first surprise, for they are well upholstered, scrupulously clean, and adorned with attractive pictures. Externally they are a narrow gauge edition of the Midland main line stock in use just before grouping took place, with high elliptical roofs and seating three a side. They ride very smoothly, and to the accompaniment of that characteristic singing rhythm that one invariably notices when running on flat-bottomed rails. The other incidental noise of travel, the beat of the engine, savours much less of a narrow gauge railway owing to there being with the compounds only two exhausts for every revolution of the driving wheels. The small diameter of the wheels makes the exhaust period almost the same as that of a 6ft. 9in. standard gauge two-cylinder simple engine.

Like the 2-4-0 engines of which I wrote in the "M.M." for September 1936, these narrow gauge tank locomotives are started up practically full compound. Live steam is admitted to both cylinders for the first stroke of the pistons, but immediately the high-pressure cylinder exhausts an automatic changeover valve operates and compound working begins. Steam distribution in both the high and low-pressure cylinders is effected by means of separate sets of Walschaerts valve gear, but both sets of gear are controlled by one reversing lever in the cab. The cabs, by the way, are only just big enough to accommodate the driver and fireman, yet strangely enough when I last travelled over the line our fireman was one of the most enormous individuals I have ever seen on a locomotive; anyone attempting to ride on the footplate would most assuredly have had to hang on to the step outside for most of the trip! On the Ballycastle line these fine little engines are not called upon for any strenuous work, and in this respect the railway may well be classed with another in the West of Ireland, which recently became a butt for Mr. Lynn Doyle's keen humour. In describing a journey on which a train was soundly beaten by an aged and ramshackle motor car running on a parallel road, he suggests that a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Engines would never have obtained a conviction against that particular line! That is not to say that the N.C.C. 2-4-2 tanks cannot run when occasion demands. Indeed, in the days of the Larne boat expresses really fine work was needed to cover the 25 miles from Ballymena in 60 minutes, climbing en route to Ballynashee summit, 650 ft. above sea level.

After leaving Ballymoney the Ballycastle branch runs through fairly level country at first, the landscape being a wide expanse of peat bogs, dotted with small single-storied cottages, and rising southward towards the Antrim highlands. Shortly before reaching Dervock, the first station, the River Bush is crossed, and then the line swings eastward through Stranocum, Gracehill, and Armoy, climbing steadily all the way until it comes almost beneath the shadow of Knocklayd, the northernmost of the Antrim mountains. These stations are classed officially as "halts," but all of them possess goods sidings, and wagons are often picked up or dropped by passenger trains. No goods trains are regularly scheduled, and the majority of the passenger trains are booked to convey goods traffic if required. The majority of the trains consist of two bogie passenger coaches and not more than one or two four-wheeled goods wagons. These capable little engines are, however, permitted to take much heavier loads when occasion demands, and on the heaviest gradient, from Ballycastle up to Capecastle, trains may be made up to seven bogie coaches, or 14 wagons and a brake van.

Beyond Armoy the route becomes very picturesque. The broad green flanks of Knocklayd sweep upward on the right, the track winds its way between high hedgerows, and the lineside is deep with waving grass. Often the journey is enlivened by the antics of a goat tethered to the boundary fence. The summit level is reached at Capecastle, after which the line descends steeply to the sea. This is a delightful stretch, with rolling hills on both sides of the line, and concluding with a pleasing glimpse of the bay as the train swings round into Ballycastle. The station is however in the upper part of the town, and this brief vista from the carriage window is but the merest fraction of the exquisite scene to be enjoyed from the shore, a scene that includes the limestone cliffs of Rathlin Island, the majestic bluff of Fair Head, and the long broken ridge of Kintyre, Scotland's nearest point.

Ballycastle station is quite a primitive affair. A single platform, curiously old-fashioned buildings suggesting the earliest days of railways, and a quaint engine-shed just big enough to house two of the compound tank locomotives, combine to produce an out-of-the-world atmosphere quite unlike the rest of the N.C.C. system. As the line is quite isolated from the other N.C.C. narrow gauge branches, its two engines have to be maintained entirely from the Ballycastle running shed. When heavy repairs are needed the locomotives are transported bodily to Belfast shops. In this connection it is of interest to recall that some of the 2-4-2 tanks were the first new engines to be constructed entirely in the N.C.C. works. Although in recent years several standard guage engines have been erected in Ireland, the components have shipped over from the Derby works of the L.M.S. In the case of 1908-9, and 1919-20 batches of compound tanks the whole of the work was done in Belfast, The standard timing of all trains is 50 minutes for the 16 1/4 mile run from Ballymoney to Ballycastle, which allows for stops at all stations. During the summer, however, there is one non-stop train, which makes the run in 40 minutes. This runs in connection with "The Golfers' Express," to Portrush. By this service Ballycastle is reached in less than two hours from Belfast.

The west of Ireland was at one time served by quite a number of such lines. A cheap type of construction can be used that is naturally attractive to the promoters of a railway planned to serve a thinly populated region where there is little chance of any heavy traffic; but in recent years most of these lines have suffered severely from road competition, train services have been reduced to a mere skeleton of their former selves, and the majority of the passenger workings have been operated by Diesel railcars. The Northern Counties Committee section of the L.M.S. however has, in the Ballycastle branch, one narrow-gauge section over which a full passenger service is still worked entirely by steam locomotives, and a more fascinating little railway it would be hard to imagine.

This branch connects at Ballymoney with the broad gauge main line from Belfast to Portrush and Londonderry; like that of the other N.C.C. non-standard routes the gauge is 3 ft. Although the branch is only 16 1/4 miles long it is an important link, and provides the quickest service to one of the most charming resorts on the Antrim coast. For a long time it was an absolutely independent concern, long after the neighbouring narrow gauge lines, the Ballymena and Larne, and the Ballymena, Cushendall and Red Bay, had been absorbed in the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway, the Ballycastle line stood out alone, and it was nearly two years after the English Midland Railway, and with it of course the N.C.C., had become part of the L.M.S, that the separate existence of the company came to an end.

Until that time traffic had been operated almost entirely by two 4-4-2 tank engines built by Kitson and Co. in 1908. They are portly looking engines of characteristic Kitson appearance, but after the amalgamation they were transferred to Ballymena to work goods trains on the Larne line. Their place on the Ballycastle Railway was at first taken by some of the 0-4-0 tank locomotives previously used on the Larne line; by their very size and quaintness these latter were irresistibly fascinating little engines, but all of them are now scrapped. When the passenger service was withdrawn on the Larne and Cushendall branches considerably fewer narrow gauge engines were needed for the whole system, and it was naturally the oldest and smallest that went to the wall.

The Ballycastle line is now being worked by two of the Class S 2-4-2 compounds, which are among the most distinctive and original tank locomotive designs that have ever been put on the road. In the "M.M." for September 1936 I described the remarkable two-cylinder compounds designed by Mr. Bowman Malcolm for the broad gauge line of the N.C.C.; in applying the Worsdell-von Borries system to the narrow gauge both cylinders had to be placed outside owing to the very restricted space between the frames. There was nothing unusual in the mere fact of the cylinders being outside, for all the other narrow gauge engines were the same in this respect; what makes the compounds look so queer when seen from the front end is that the cylinders are of different sizes. The high-pressure cylinder is 14 3/4 in. diameter, and the low-pressure 21 in. diameter, both having a stroke of 20 in.

The engines were originally designed to work on the Ballymena and Larne line, over which a boat express used to be run in connection with the Stranraer steamer. This train was timed quite fast for a narrow gauge line, and the stiff ascent to Ballynashee summit involved some strenuous locomotive work. In view of this duty they were provided with side tanks of large capacity. The first two of these engines were built by Beyer Peacock in 1892; two further engines were added to the stock in 1908-9, and it is these two that are now working on the Ballycastle line, namely Nos. 101 and 102. The last two of the type were constructed as recently as 1919-20. One of the 1892 engines, No. 110, has recently been rebuilt with a Belpaire boiler having 200 lb. per sq. in. pressures, and this alteration and the consequent increase in weight have necessitated its conversion to the 2-4-4 wheel arrangement. All these narrow gauge engines are painted Midland red, and look very fine. The two original 2-4-2 engines were painted in the bright myrtle-green livery of the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway. They were lined out in white and red in a manner very similar to that of the former L.N.W.R., and the likeness was heightened by the cast number plates, having raised figures on a bright orange ground. After the Midland took over, all the Northern Counties engines were painted a pleasing shade of olive-grey, known officially as "invisible green."

Coming now to the Ballycastle line itself, the track layout at Ballymoney is quite complicated. Narrow gauge passenger trains are accommodated alongside the up main line platform, but there is an extensive broad gauge goods yard on the up side for dealing with the large cattle traffic. Not only this, but by running broad and narrow gauge goods lines alongside each other the transhipment of merchandise for the Ballycastle branch is made much easier. The presence of this big goods yard however means that broad gauge shunting, and goods movements to and from the main line, are carried out right across the narrow gauge tracks; accordingly the points and signals of both gauges are all interlocked with one another just as though they were part of the same system. The narrow gauge signals have miniature arms carried much lower than the usual height. Once clear of Ballymoney yard signalling presents no difficulties, for the branch is worked on the "one engine in steam" principle. The two locomotives shedded at Ballycastle are used on alternate days, one being sufficient to work the whole day's service. The branch possesses only two engine crews; whichever locomotive is doing the day's work is remanned in the early afternoon, the two pairs of men working "early" and "late" turn on alternate weeks.

Once a traveller alights from the main line train at Ballymoney and goes over to the branch platform, all the traditional bustle and efficiency of the N.C.C. system is gone in a flash, or so it seems. Here is the perfect Irish joke of a railway. Passengers join in lively badinage with enginemen and guard, the fireman is solemnly recoaling the engine from wicker baskets, and a stranger feels as though he has dropped in at some intimate family party rather than a serious transportation concern. But this homely happy-go-lucky sort of atmosphere reflects anything but the true character of the line, which despite outward appearances is just as efficient and reliable as any other part of the N.C.C., which, renowned as it is for strict punctuality, is saying a great deal.

The somewhat primitive method of refuelling the narrow gauge engines at Ballymoney is of course due to the absence of any form of mechanical coaling appliance. All coal used on the N.C.C. is imported from Scotland, and supplies for the Ballycastle line are sent down from Belfast and transferred at Ballymoney into small baskets so as to be easily handled by the local firemen. The engines are watered from a picturesquely old-fashioned tank built up on brick pillars on the extreme far side of Ballymoney goods yard, and in consequence on each trip locomotives have to make quite a number of reversing movement in order to replenish their tanks. To a stranger preparing, according to his nature, either to enjoy or bemoan the joke; the carriage interiors provide the first surprise, for they are well upholstered, scrupulously clean, and adorned with attractive pictures. Externally they are a narrow gauge edition of the Midland main line stock in use just before grouping took place, with high elliptical roofs and seating three a side. They ride very smoothly, and to the accompaniment of that characteristic singing rhythm that one invariably notices when running on flat-bottomed rails. The other incidental noise of travel, the beat of the engine, savours much less of a narrow gauge railway owing to there being with the compounds only two exhausts for every revolution of the driving wheels. The small diameter of the wheels makes the exhaust period almost the same as that of a 6ft. 9in. standard gauge two-cylinder simple engine.

Like the 2-4-0 engines of which I wrote in the "M.M." for September 1936, these narrow gauge tank locomotives are started up practically full compound. Live steam is admitted to both cylinders for the first stroke of the pistons, but immediately the high-pressure cylinder exhausts an automatic changeover valve operates and compound working begins. Steam distribution in both the high and low-pressure cylinders is effected by means of separate sets of Walschaerts valve gear, but both sets of gear are controlled by one reversing lever in the cab. The cabs, by the way, are only just big enough to accommodate the driver and fireman, yet strangely enough when I last travelled over the line our fireman was one of the most enormous individuals I have ever seen on a locomotive; anyone attempting to ride on the footplate would most assuredly have had to hang on to the step outside for most of the trip! On the Ballycastle line these fine little engines are not called upon for any strenuous work, and in this respect the railway may well be classed with another in the West of Ireland, which recently became a butt for Mr. Lynn Doyle's keen humour. In describing a journey on which a train was soundly beaten by an aged and ramshackle motor car running on a parallel road, he suggests that a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Engines would never have obtained a conviction against that particular line! That is not to say that the N.C.C. 2-4-2 tanks cannot run when occasion demands. Indeed, in the days of the Larne boat expresses really fine work was needed to cover the 25 miles from Ballymena in 60 minutes, climbing en route to Ballynashee summit, 650 ft. above sea level.

After leaving Ballymoney the Ballycastle branch runs through fairly level country at first, the landscape being a wide expanse of peat bogs, dotted with small single-storied cottages, and rising southward towards the Antrim highlands. Shortly before reaching Dervock, the first station, the River Bush is crossed, and then the line swings eastward through Stranocum, Gracehill, and Armoy, climbing steadily all the way until it comes almost beneath the shadow of Knocklayd, the northernmost of the Antrim mountains. These stations are classed officially as "halts," but all of them possess goods sidings, and wagons are often picked up or dropped by passenger trains. No goods trains are regularly scheduled, and the majority of the passenger trains are booked to convey goods traffic if required. The majority of the trains consist of two bogie passenger coaches and not more than one or two four-wheeled goods wagons. These capable little engines are, however, permitted to take much heavier loads when occasion demands, and on the heaviest gradient, from Ballycastle up to Capecastle, trains may be made up to seven bogie coaches, or 14 wagons and a brake van.

Beyond Armoy the route becomes very picturesque. The broad green flanks of Knocklayd sweep upward on the right, the track winds its way between high hedgerows, and the lineside is deep with waving grass. Often the journey is enlivened by the antics of a goat tethered to the boundary fence. The summit level is reached at Capecastle, after which the line descends steeply to the sea. This is a delightful stretch, with rolling hills on both sides of the line, and concluding with a pleasing glimpse of the bay as the train swings round into Ballycastle. The station is however in the upper part of the town, and this brief vista from the carriage window is but the merest fraction of the exquisite scene to be enjoyed from the shore, a scene that includes the limestone cliffs of Rathlin Island, the majestic bluff of Fair Head, and the long broken ridge of Kintyre, Scotland's nearest point.

Ballycastle station is quite a primitive affair. A single platform, curiously old-fashioned buildings suggesting the earliest days of railways, and a quaint engine-shed just big enough to house two of the compound tank locomotives, combine to produce an out-of-the-world atmosphere quite unlike the rest of the N.C.C. system. As the line is quite isolated from the other N.C.C. narrow gauge branches, its two engines have to be maintained entirely from the Ballycastle running shed. When heavy repairs are needed the locomotives are transported bodily to Belfast shops. In this connection it is of interest to recall that some of the 2-4-2 tanks were the first new engines to be constructed entirely in the N.C.C. works. Although in recent years several standard guage engines have been erected in Ireland, the components have shipped over from the Derby works of the L.M.S. In the case of 1908-9, and 1919-20 batches of compound tanks the whole of the work was done in Belfast, The standard timing of all trains is 50 minutes for the 16 1/4 mile run from Ballymoney to Ballycastle, which allows for stops at all stations. During the summer, however, there is one non-stop train, which makes the run in 40 minutes. This runs in connection with "The Golfers' Express," to Portrush. By this service Ballycastle is reached in less than two hours from Belfast.