Marconi and Ballycastle

It is amazing how the most outlying places can, at times, link up with the great names of the world. Rathlin Island - a hilly fragment of land only some five miles long and one-and-a-quarter miles broad at the most - is mentioned by Pliny as an island between Ireland and Britain, while the celebrated Egyptian mathematician, astronomer and geographer, Ptolemy, who lived in the second century A.D. and who wrote a description of the various countries of Europe, illustrated with maps and prepared under his direction, also refers to it in his geography.

It is truly remarkable that the island was known to Pliny and Ptolemy, celebrated Latin and Greek authors respectively, just as it possesses an interesting contact with the early development of wireless telegraphy.

Born at Bologna on April 25th, 1874, Guglielmo Marconi was the second son of Guiseppe Marconi, an Italian country gentleman, his mother being a daughter of Mr. Andrew Jameson, of Daphne Castle in the County of Wexford. Marconi's first wife - like his mother - was also an Irish woman - the Honourable Beatrice O'Brien, daughter of the fourteenth Baron Inchiquin of Dromoland Castle in the County of Clare.

Genius and Perseverance

Marconi was not the discoverer of electric waves: he was not even the first to suggest that they might be used for signalling to long distances, but thanks to his genius and perseverance, it is due to him more than to any other single worker, that they are now one of the most important means of communication. Wireless has conferred inestimable benefits on the mariner by enabling him to keep in touch with the rest of the world and helping him to safety in his course across the oceans; and broadcasting, a direct outcome of Marconi's work, has taken rank among the necessaries of life.

Marconi was educated at the University of Leghorn and at the university of his native city - Bologna – generally regarded as the oldest university foundation in the world. At Bologna he studied under Adolfo Righi, himself the author of important investigations on electric waves.

His first attempts to turn Hertz's laboratory work to practical use for the transmission of signals to a distance were made at his father's villa at Pontecchio, near Bologna and at an early stage in his experiments he effected a fundamental improvement, which at once gave him results far ahead of those obtained by other workers in the same field, by employing with both his transmitter and his receiver elevated conductors or aerials in combination with metallic connections to earth. For the detection of the electric waves at the receiving end he used the "coherer" of Branly and Lodge, on the improvement of which he worked between 1894 and 1896.

His First Patent

It was in May, 1896, that Marconi, then a retiring, modest young man of 22, unknown and almost without friends, first came to England, and it was in this year that he took out his first patent. Upon his arrival in London he lost no time in presenting his credentials to Sir William Preece, the eminent electrician and then engineer-in-chief of the General Post Office. Marconi was fortunate enough to enlist the interest of Sir William Preece, who gave the young scientist substantial assistance.

It was also at this stage that Marconi came into contact with a very remarkable man in the person of George Stephen Kemp, who, on leaving the Royal Navy, became laboratory assistant to Sir William Preece. Kemp was detailed by Sir William Preece to work with Marconi in the first demonstrations of wireless telegraphy given in these islands to officials of the Post Office and other Government Departments.

Successful tests in the City of London between St. Martins-Le-Grand and the Thames Embankment were followed by transmissions across Salisbury Plain, when signals were received at a distance of two or three miles from the transmitter. These transmissions were among the first experiments in which Marconi and his assistant were engaged.

Floated Company

A further successful experiment on Salisbury Plain later in the year 1897 brought sufficient public confidence to enable Marconi to float the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company. In demonstrations carried out for the Italian Government in the same year at Spezia, signals were sent for a distance of twelve miles.

In 1898 Marconi erected permanent stations in the Isle of Wight, near the Needles. It was from the Royal Needles Hotel that the first paid-for wireless message was sent.

The veteran scientist, Lord Kelvin, sometime Professor of Natural Philosophy in the University of Glasgow and a native of Belfast - his statue may be seen at the entrance to the Botanic Gardens in that city - accompanied by Lady Kelvin and the Poet Laureate, A1fred, Lord Tennyson, went to the station at the Needles to see for himself the working of the new system of telegraphy. Lord Kelvin was keenly interested and asked the young scientist if he might be allowed to send telegrams to some of his friends. He insisted on paying one shilling for each message in token of his belief in the commercial possibilities of wireless telegraphy.

Historic Occasion

This historic occasion took place on 3rd June, 1898, and caused a good deal of favourable newspaper comment. Kemp thus recorded the event in his diary:

"June 3rd, 1898. Gave a show to Lord and Lady Kelvin and Lord Tennyson, who sent and paid for their messages. One of these was for Sir William H. Preece, via Bournemouth by wireless and then by land lines. At 3.15 I left for Waterloo Station, London.

It is of great interest that immediately after this all-important demonstration on 3rd June, the next day (June 4th) Kemp set off from London to Ballycastle. He was in Ballycastle conducting wireless experiments from Saturday, June 4th, to Monday, July 6th, and from Monday, July 25th, to Thursday, September 8th, 1898. Marconi did not accompany him to Ballycastle on 4th June, and probably for a very good reason.

The young scientist was able to be of service to Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VII), both of whom were then at Osborne in the Isle of Wight. The Prince had the misfortune to slip and fall heavily upon one knee, injuring it so severely that it was at first feared that his limb might be stiff for the rest of his life. His Royal Highness was compelled to remain on board the Royal Yacht, which was anchored in Cowes Bay.

Messages to Royal Yacht

The Prince who had already taken a deep interest in wireless telegraphy, thought that it might be possible to establish communications in this way between the yacht and Osborne house, where the Queen was staying. Marconi was approached and was naturally delighted to place his knowledge and skill at the service of the Queen. Two stations, one on board the yacht and the other at Osborne House, were soon established and in working order.

For the next 16 days, while Kemp was proceeding with his experiments at Ballycastle, Marconi was on board the Royal Yacht, sending altogether about 15O messages by wireless telegraphy. Not one of these messages had to be repeated.

The new system of wireless telegraphy attracted widespread attention and remarkable progress was made in the next few years. Before the year 1898 had run its course, messages were being sent successfully between such places as Ballycastle and Rathlin Island and between the South Foreland Ligththouse and the East Goodwin Lightship. The wireless experiments between Ballycastle and Rathlin in the summer of 1898 and extending over the months of June, Ju1y, August and early September were the first such demonstrations for Lloyds.

Eventful Summer

It was at their instance that they were conducted. The summer of 1898 must have been a particularly eventful one in the life of Ballycastle. On July 30th the town was thrown into a state of excitement by the arrival of a couple of motor cars. These had come round from Larne via Cushendall, and put up for a time at the Marine Hotel. They subsequently left for the Giant's Causeway.

Both cars had a full complement of passengers, most of whom were English tourists, who had been staying at Henry McNeill's, Ltd., Larne. During their short stay the motors were surrounded by quite a crowd, taking a lively interest in this, the first visit of a motor car to Ballycastle. The present lovely weather has attracted a considerable number of visitors and the town presents quite an animated appearance - so ran a contemporary report of the occasion.

Gottlieb Daimler thirteen years previously, patented a light high-speed two cylinder petrol engine. Later much used in motor cars, I might also add that it was in this memorable year - 1898 in Ballycastle that the Ballycastle Lawn Tennis Club held its first annual tennis tournament.

Complaints from Lloyds

The wireless experiments at Ballycastle were the outcome of complaints by Lloyds of not being able to report steamers from Torr Head, a Lloyds signalling station on the north-east corner of Ireland, and this in spite of the fact that these steamers were able to report to what is now known as Rathlin East lighthouse. Ships passed close to this lighthouse, off Altacarry Point and even in a fog they could signal their numbers, etc., by means of flags; but be this as it might, Rathlin had no means of conveying this information to Torr Head by flag signals.

"Lloyds requested me", says Kemp, "to fit a wireless station at Rathlin Lighthouse and another at Ballycastle, and I travelled on to Ballycastle at 1 p.m. on Saturday, June 4th, from which place I communicated with Lloyd's agent, Mr. Byrne, at 11 a.m. Studied the plans and surveyed the coasts of the North of Ireland and Rathlin Island. The mast at the Lighthouse was 60 feet high and 30 feet from Lloyd's hut. I left Ballycastle with Mr. Wyse and inspected Rathlin Island returning at 6.10 p.m.

Four Stages

In the course of the wireless experiments at Ba1lycastle during the summer of 1898, four stages may be noted:

Stage 1 began on Friday, June 10th, when Kemp met Mr. Hough from Lloyds in Ballycastle at 11 a.m. They arranged to experiment at the coal store, now the Pier Pavilion, with the aerial leading over the road to a small mast on top of the cliff, now the car park, almost opposite Hilsea Hotel. This mast was that appertaining to the coastguard station.

This is generally believed to have been the first wireless installation ever set up in Ireland. Next day Kemp and Hough went to Rathlin and upon their return, Kemp fitted up the station in the coalyard. The following Monday, Kemp started teaching Lloyd's agent, Mr. Byrne, and his sons, the Morse code in the hope of getting their help until Lloyds sent someone to take charge of the station.

Four days later Kemp was in Belfast where he tried, unsuccessfully as it proved, to obtain masts for the Rathlin and Ballycastle stations. On June 22nd and June 23rd, 50 Obach cells for transmission were fitted at the coalyard station at Ballycastle Quay, and 50 were fitted at the Lighthouse station on Rathlin. Mr. Byrne and his sons received further instruction from Kemp, this time in the working of the coalyard station.

Short First Stage

On 2nd July, wire and insulators arrived in Ballycastle from London "by the last train" (as Kemp describes it), and by July 5th half the wire, insulators and stores were taken to Rathlin Island and fitted up at the station there for transmission. Kemp instructed Signalman Dunovan and his two sons in the working of the station. Next day news came from London to the effect that Kemp was to take all the apparatus - "half a ton of gear," as he calls it - from Ballycastle to Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire), for the Kingstown annual regatta.

So ended Stage I - a very short-lived one - in the fitting up of the two experimental stations at Ballycastle and Rathlin. What happened at Kingstown does not concern us here, suffice it to say that the apparatus was employed to transmit reports of Kingstown Regatta to a Dublin newspaper - The Daily Express - from a steamer, "The Flying Huntress," in Dublin Bay. Mr. Marconi himself was present at these experiments - the first ever of messages being sent from sea to land by a vessel in motion.

Upon the conclusion of the regatta, Kemp and a young man named Edward Edwin Glanville, a native of Blackrock, an engineering student at Trinity College, Dublin, and employed as assistant to Marconi, set out by train from Dublin to Ballycastle. This brings us to Stage II in our story of the early wireless experiments in Ballycastle.

Aerial on Spire

Glanville was put in charge of the Rathlin Island station with instructions to transmit to Kemp at the Ballycastle end every day. "I received at various places," says Kemp in his diary, "and on the cliffs along the coast in the vicinity of Ballycastle and received the best results on an aerial connected to the Roman Catholic church spire in Ballycastle, but as there was no house or room available here - and the Company would not let me use a hut - there was not much chance to make a speedy job, as there was delay in getting spares from Belfast."

The chapel spire must then have presented a very new appearance; it had been added to the building in 1891, thanks to the John Lawless bequest, as the chapel itself dates from 1870. Kemp is at pains to state that these good results were the outcome of the courtesy and co-operation extended by the Parish Priest, the Very Rev. John Conway, V.F. Little wonder that later on in the course of the experiments - in September - when Marconi came to Ballycastle, he and Kemp showed their appreciation of this favour by calling on the Very Reverend gentleman, presumably at the parochial house on the day before they left Ballycastle for London.

Stage III in the experiments followed when Kemp managed (as he tells us) "to get the loan of a small bedroom in a lady's house on the cliff, and the loan of a jib of a crane in the pier yard (now the car park) which served me for a lowermast." This house, as Marconi subsequently explained to Kemp, belonged to Mr. Thomas Magregor Greer, M.A., T.C.D., Solicitor, Ballymoney, and now known as White Lodge, is the property and residence of Colonel H. A. Allen, D.S.O, At the time of the wireless experiments it was rented by Mr. Greer's brother-in-law, Mr. Talbot Reed, of 1, Hampstead Lane, Highgate, in the City of London.

Tragedy on Rathlin

A sad tragedy occurred on Sunday, August 27, in the course of the third stage of the experiments when Young Glanville, out for a walk on Rathlin on that afternoon accidentally fell over a cliff and was killed. This sad accident was quite unconnected with the experiments. The people on the island had often seen Glanville, who was interested in geology, climbing over the cliffs and this was no doubt the cause of the accident.

The verdict at the inquest was accidental death, but the jury, presided over by Mr. J.P. O'Kane, father of Mrs. Boylan, added the following rider - "That we beg to tender our deepest sympathy with the parents of the deceased, and also with Mr. Kemp and the other members of the staff of the Wireless Telegraph Company, with whom the deceased worked so cordially and we desire to place on record our sorrow at such a tragic ending to so promising a career, connected as it was with one of the most important discoveries of the century."

Mr. Glanville's body was taken to the mainland by the s.s. "Glentow" and from thence by rail to Dublin, for burial.

We now come to the fourth and - last stage of the early wireless experiments in Ballycastle seventy years ago almost to the day. On August 24 Kemp proceeded to erect a new mast in a field 104 feet to the top of the sprit and 104 feet from the window of a child's bedroom, which was loaned to him, at the northern side of what is now Colonel Allen's house. Thus two different bedrooms in this house were used in the course of Stage III and Stage IV of the early wireless experiments in Ballycastle.

Next day Kemp states that he finished the station and adjusted the receiver and inker. He instructed Mr. Byrne in all the details of the transmitter and requested him to follow when he received the dots and dashes from Kemp on the inker. He sent messages to, and received messages from, Mr. Byrne until 1 p.m. on that day, left the station on Rathlin in charge of Mr. Dunovan and Mr. Dunovan's two boys and returned to Ballycastle.

Satisfactory Experiments

This trip from the island to the mainland must have been something in the nature of an adventure for Kemp, as it took four hours to cross what he describes as "that very dangerous piece of water, and I caught a terrible cold." The experiments were now apparently proving very satisfactory, as next day messages were sent and received from 10 a.m. to 6.30 p.m., mostly red each way. Ten ships were reported and Lloyds' agent (Mr. Byrne) sent a report to Lloyds concerning the days’ work which had been carried out in a dense fog. The following day, August 27th, two more ships were reported to Lloyds.

The rough passage from Rathlin two days previously had evidently proved too much for Kemp, because he had to go "to bed suffering from Neuralgia and fever. The weather was very windy and wet during the day and I was forced to keep the window open - presumably the window in the child's bedroom - mentioned in the diary under August 24th - to enable me to transmit, and this increased the violent cold that I caught in the boat." Conditions were no better by August 28th. "Weather," writes Kemp, "still very wet and wind blowing a gale. I had to remain in bed, taking medicine which reduced the fever, but made me very weak."

Marconi's Arrival

Kemp must have been a somewhat sick man when next day - Monday, August 29th, the eve of the Lammas Fair - Mr. Marconi arrived in Ballycastle by the 6.15 p.m. train. One is tempted to wonder how the young scientist at 24 contemplated the scene as the narrow gauge train in which he was travelling neared its journey's end by rounding the sharp Ballylig curve, with its check rail, and passing Broombeg Wood, later replanted and now known as Ballycastle Forest, finally arrived at the Ballycastle railway terminus; the engine driver had sounded the whistle at the distant signal at Kilcraig and the train passengers surely knew that Ballycastle could not now be far off.

Was Marconi, as he made his way from the station to the Antrim Arms Hotel, almost certainly by way of the Poor Row or Station Street, interested in the stalls erected on the Diamond in readiness for the Fair next day or was he more concerned with his scientific pursuits? P.W.Paget, one of his technical assistants, has left it on record that Marconi had little interest in anything outside wireless. In any event, he may have been too deeply concerned about the death by accident of his assistant, Glanville, only a week previously to bother much about the fair. Certainly he remained indoors in the Antrim Arms Hotel all the evening.

On Lammas Fair Day

Next day - the Lammas Fair day - Kemp called up Rathlin Island station and found that they had broken their sensitive tube. "I told them," he says, "to stop for a few days. The weather was still very wet and windy and I spent the remainder of the day packing apparatus and transporting it to the Antrim Arms Hotel. I told Mr. Byrne that he would have to get a station built for carrying on further work, as the present room. i.e., the child's bedroom, must be given up because Mr. Greer of Ballymoney, the owner of the house was coming back. I tried to go to Rathlin, but found that no boat had been there since August 25th when I crossed."

On the second day of the Lammas Fair, Kemp tried to get a boat to take Marconi and himself to Rathlin, but no one would venture to cross. Instead, the scientist and his assistant went to Fair Head, whence they saw Rathlin, Torr Head, the Mull of Kintyre and the two islands at the mouth of the Clyde - Sanda and Ailsa Craig.

One of the Largest

What sort of fair was the Lammas Fair which was held during Marconi's visit to this town and some of which he must have seen, whether he was interested in what he saw of it or not? As a matter of fact it was one of the largest held in the district for years. Buyers from Belfast, Derry and Armagh and cross-channel attended, some even before the day of opening. It is believed that it would have been the most successful fair held here for years, but unfortunately at eleven o'clock and up to seven p.m. a continuous heavy downpour of rain set in and damped those attending and practically spoilt the day. The second day compensated by being gloriously fine, but the rain of the previous day acted on the attendance.

There was a great show of sheep, cattle and horses and prices were as follows -Bullocks, first class £14 to £17; second class £11 10s to £14; third class to £9 to £11; heifers, first class £12 to £16 10s; second class £€10 to £12; third class £7 to £10. Milch cows £14 to £16 and £9 to £11. Sheep from 17s 6d to 42s. A large sale was made in this class; lambs 18s to 33s; Bullocks 27s per cwt.; middling class 23s 6d per cwt.

There was a splendid show of Cushendall ponies. The Islay fish trade was most successful, ling, cod, etc., being in abundance. All the lots were sold from 3s 6d to 7s 6d a bundle. In the fruit market there was a great supply. The lots were chiefly brought by wholesale traders from Ballymena and Belfast. Such were the chief characteristics of the Ballycastle Lammas fair of seventy years ago.

Crossing to Rathlin

On Thursday, 1st September, Mr. Marconi and Kemp started from Ballycastle at 9 a.m. and crossed to Rathlin in one hour with, as Kemp describes it, "a fair wind and large sail." They visited the lighthouse, beside which the aerial mast was erected; some of the cement blocks inscribed "Lloyds" and used to hold the stays of the mast may still be seen there.

As a memorial of the early wireless experiments here, it is surely possible for one of these to be brought to Ballycastle and placed somewhere for all to see in the new promenade or municipal gardens as described in Mr. Fergus Pyle's article on "Civic Week in Ballycastle", in the "Irish Times."

Marconi and Kemp found that the ridge of Lloyds' land bore north and south and that the station at Ballycastle bore south-south-west. Kemp induced Mr. Dunovan and his sons to pack up the apparatus while he took Mr. Marconi to Ballyconagan to see the cliff where Glanville lost his life. Thus by early September, 1898, the experiments came to an abrupt end at Ballycastle. Whether or not the accidental death of Glanville on Rathlin had anything to do with this it is impossible to say.

Thanked for Co-operation

Mr. Marconi and his assistant returned to Ballycastle at 2 p.m. "pulling and sailing in 1 1/2 hours." Upon their return they visited the Very Rev. John Conway, P.P., V.F., the proprietors of the Water Mill - presumably that of Messrs. Alex. and John Nicholl, and the landowners; presumably the agent to the local estate. This was evidently to thank each of these parties for their help and co-operation during the experiments.

Next day, September 2nd, Mr. Marconi left for London and Kemp took down the mast that he had erected 104 feet north of Greer's house at the top of the Quay Hill and returned all the stores to the Antrim Arms Hotel. Six days later, on September 5th, Kemp left Ballycastle for London, - travelling via Belfast and Fleetwood.

Kemp regarded the Ballycastle experiments as very successful demonstrations in spite of the circumstance that he had to work (as he put it) under the most peculiar instructions ever given to him. In 1897 the whole of the G.P.O.'s skill was put on to a similar job, but in the case of the Ballycastle/Rathlin experiments, carried out under the auspices of Lloyds, he was sent (as he says) in that case without any assistance and complains that he had to instruct all those who helped him.

Not Until 1905

Apparently the relationships between Kemp and Lloyds were not as friendly as those between Kemp and the G.P.O. At all events the Marconi system of wireless telegraphy between Ballycastle and Rathlin was not brought into use until 1905. It replaced the parallel system which was the first system between Ballycastle and Rathlin and was, of course, quite distinct from the experiments I have described, which, as I have explained, were carried out under the auspices of Lloyds, whereas the parallel system was a purely G.P.O, affair.

Despite the somewhat adverse criticisms of Kemp in his relationship with Lloyds, the Ballycastle/Rathlin experiments must, nevertheless, have had some definite significance in the development of wireless telegraphy. Within two years, in 1900, Marconi had taken out his famous patent No. 7777 for "tuned or syntonic telegraphy."

He had transmitted signals to such a distance - over 200 miles - as to convince him that the electric waves, instead of being projected into space, as some prophets averred would be the case, would, as it were, cling to the surface of the earth, the curvature of which would, therefore, be no bar to the attainment of long ranges. Accordingly, he determined to make an attempt to send signals across the Atlantic, and for that purpose proceeded to erect a powerful station at Poldhu, in Cornwall, with a similar station at Cape Cod, in the United States of America.

Wrecked by Storm

The masts and aerial at Poldhu were wrecked by a storm in September, 1901, and though they were repaired by the end of November a similar mishap at Cape Cod threatened to delay the test for several months. To save time he went to Newfoundland and installed his instruments in a disused barracks on Signal Hill, St. John's. He had intended to support his aerial by a balloon, but as this was blown away, he substituted a kite which, with great difficulty owing to the strong wind, was kept at a height of about four hundred feet.

It had previously been arranged that at fixed times the Poldhu station should send out the signal for the letter 'S' on the Morse code - three dots - and on December 12th, 1901, both he and Kemp, using a self-restoring coherer, repeatedly heard in their telephone the three clicks which showed that the electric waves had traversed the 1,800 miles separating St. John's from Poldhu.

This momentous incident was recalled by Mr. P. W. Paget, Marconi's first technical assistant in these words - "I was with him at Signal Hill, Newfoundland, when he received the first wireless signal - the letter 'S'- ever transmitted across the Atlantic. It was from the station at Poldhu, Cornwall. He showed no excitement, calmly handing over the earphones first to Mr. George Stephen Kemp, who was also assisting him, and then to me, with the words - 'Can you hear this?' He was never unduly elated and never unduly depressed. When the twenty masts, erected at Poldhu for the Transatlantic transmission collapsed in a gale, Marconi looked at the wreckage and said quietly to me - 'Well, they will be built again.' That was all. Marconi had few hours of sleep. He had little interest in anything outside wireless.

Commercial Basis

Soon afterwards preparations were begun for the establishment of wireless telegraphy between England and America on a commercial basis. We are reminded here of those words of Longfellow:-

The heights by great men reached and kept

Were not attained by sudden flight,

But they, while their companions slept,

Were toiling upward in the night.

"At that time" (1901), wrote Marconi, "and for long afterwards, certain important sections of the technical Press in this country were against me, and spared no efforts in their determination to discredit both me and the work on long-distance wireless communication. From the first, however, 'The Times' declared its belief in me, and was swift and forceful to rebuke those who persisted in a policy of disparagement. Radio has made very great strides since 1901, and yet I often look back to those early days and remember with deep gratitude what a wonderful encouragement of support it was to me to know that a great newspaper like 'The Times' had faith in me. Even as regards my work relating to the utilization of electric waves for world wide communication."

In the words of his contemporary, Rudyard Kipling, Marconi was one of those who could "meet with triumph and disaster and treat those two imposters just the same."

Retained Vigour of Youth

To the end of his life Marconi retained the vigour of youth, which was also apparent in his personal appearance. He died on 20th July, 1937 at the age of sixty-three. Kemp pre deceased him by four years. Marconi described Kemp as his first assistant, collaborator and friend, and would always be regarded as a pioneer of the wonderful science of wireless telegraphy.

When Marconi was about to be admitted to the honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law in the University of Oxford, he was referred to as " the magician who found a means of transmitting signals from shore to shore and from ship to ship."

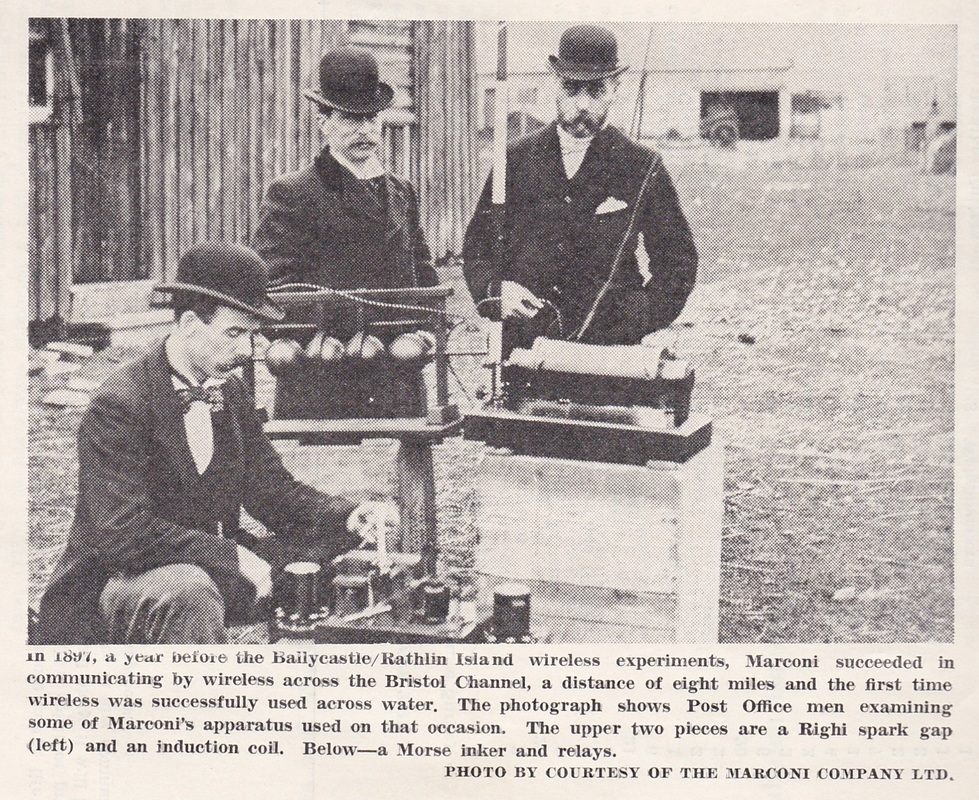

Granted that the association of this locality with wireless telegraphy in its infancy is due entirely to the first demonstration for Lloyds so as to facilitate shipping, may have been of little significance, as compared, let us say, with the Poldhu - Newfoundland transmissions, nevertheless, Kemp's installation of apparatus in Ballycastle in June, 1898 - apparatus that would have included a Righi spark gap and an induction coil, a Morse inker and relays - was almost certainly the first of its kind in Ireland. It is true that Preece was already conducting his own experiments with wireless by the induction method, which made use of long parallel wires, and that subsequently such a method was established between Ballycastle and Rathlin and was a purely Post Office affair. The service (sparking coil, coherer, etc.) established in 1898 at the request of Lloyd's Shipping Agency terminated - it would appear rather abruptly – in September 1898 because of objections on the part of the Post Office authorities. Post Office engineers carried out tests of their own by an induction method. This involved a heavy gauge wire carried on poles and down into the sea at Murlough Bay. In 1905 or 1906 the Marconi Company was again asked to install its system because, by that time, it had overcome opposition and was well established. But be all this as it may, the Ballycastle - Rathlin trials undoubtedly stand out in the history of wireless communication and in states unborn and accents yet unknown, wireless discoveries and developments will still be broadening their influence upon the lives of men.

It is amazing how the most outlying places can, at times, link up with the great names of the world. Rathlin Island - a hilly fragment of land only some five miles long and one-and-a-quarter miles broad at the most - is mentioned by Pliny as an island between Ireland and Britain, while the celebrated Egyptian mathematician, astronomer and geographer, Ptolemy, who lived in the second century A.D. and who wrote a description of the various countries of Europe, illustrated with maps and prepared under his direction, also refers to it in his geography.

It is truly remarkable that the island was known to Pliny and Ptolemy, celebrated Latin and Greek authors respectively, just as it possesses an interesting contact with the early development of wireless telegraphy.

Born at Bologna on April 25th, 1874, Guglielmo Marconi was the second son of Guiseppe Marconi, an Italian country gentleman, his mother being a daughter of Mr. Andrew Jameson, of Daphne Castle in the County of Wexford. Marconi's first wife - like his mother - was also an Irish woman - the Honourable Beatrice O'Brien, daughter of the fourteenth Baron Inchiquin of Dromoland Castle in the County of Clare.

Genius and Perseverance

Marconi was not the discoverer of electric waves: he was not even the first to suggest that they might be used for signalling to long distances, but thanks to his genius and perseverance, it is due to him more than to any other single worker, that they are now one of the most important means of communication. Wireless has conferred inestimable benefits on the mariner by enabling him to keep in touch with the rest of the world and helping him to safety in his course across the oceans; and broadcasting, a direct outcome of Marconi's work, has taken rank among the necessaries of life.

Marconi was educated at the University of Leghorn and at the university of his native city - Bologna – generally regarded as the oldest university foundation in the world. At Bologna he studied under Adolfo Righi, himself the author of important investigations on electric waves.

His first attempts to turn Hertz's laboratory work to practical use for the transmission of signals to a distance were made at his father's villa at Pontecchio, near Bologna and at an early stage in his experiments he effected a fundamental improvement, which at once gave him results far ahead of those obtained by other workers in the same field, by employing with both his transmitter and his receiver elevated conductors or aerials in combination with metallic connections to earth. For the detection of the electric waves at the receiving end he used the "coherer" of Branly and Lodge, on the improvement of which he worked between 1894 and 1896.

His First Patent

It was in May, 1896, that Marconi, then a retiring, modest young man of 22, unknown and almost without friends, first came to England, and it was in this year that he took out his first patent. Upon his arrival in London he lost no time in presenting his credentials to Sir William Preece, the eminent electrician and then engineer-in-chief of the General Post Office. Marconi was fortunate enough to enlist the interest of Sir William Preece, who gave the young scientist substantial assistance.

It was also at this stage that Marconi came into contact with a very remarkable man in the person of George Stephen Kemp, who, on leaving the Royal Navy, became laboratory assistant to Sir William Preece. Kemp was detailed by Sir William Preece to work with Marconi in the first demonstrations of wireless telegraphy given in these islands to officials of the Post Office and other Government Departments.

Successful tests in the City of London between St. Martins-Le-Grand and the Thames Embankment were followed by transmissions across Salisbury Plain, when signals were received at a distance of two or three miles from the transmitter. These transmissions were among the first experiments in which Marconi and his assistant were engaged.

Floated Company

A further successful experiment on Salisbury Plain later in the year 1897 brought sufficient public confidence to enable Marconi to float the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company. In demonstrations carried out for the Italian Government in the same year at Spezia, signals were sent for a distance of twelve miles.

In 1898 Marconi erected permanent stations in the Isle of Wight, near the Needles. It was from the Royal Needles Hotel that the first paid-for wireless message was sent.

The veteran scientist, Lord Kelvin, sometime Professor of Natural Philosophy in the University of Glasgow and a native of Belfast - his statue may be seen at the entrance to the Botanic Gardens in that city - accompanied by Lady Kelvin and the Poet Laureate, A1fred, Lord Tennyson, went to the station at the Needles to see for himself the working of the new system of telegraphy. Lord Kelvin was keenly interested and asked the young scientist if he might be allowed to send telegrams to some of his friends. He insisted on paying one shilling for each message in token of his belief in the commercial possibilities of wireless telegraphy.

Historic Occasion

This historic occasion took place on 3rd June, 1898, and caused a good deal of favourable newspaper comment. Kemp thus recorded the event in his diary:

"June 3rd, 1898. Gave a show to Lord and Lady Kelvin and Lord Tennyson, who sent and paid for their messages. One of these was for Sir William H. Preece, via Bournemouth by wireless and then by land lines. At 3.15 I left for Waterloo Station, London.

It is of great interest that immediately after this all-important demonstration on 3rd June, the next day (June 4th) Kemp set off from London to Ballycastle. He was in Ballycastle conducting wireless experiments from Saturday, June 4th, to Monday, July 6th, and from Monday, July 25th, to Thursday, September 8th, 1898. Marconi did not accompany him to Ballycastle on 4th June, and probably for a very good reason.

The young scientist was able to be of service to Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VII), both of whom were then at Osborne in the Isle of Wight. The Prince had the misfortune to slip and fall heavily upon one knee, injuring it so severely that it was at first feared that his limb might be stiff for the rest of his life. His Royal Highness was compelled to remain on board the Royal Yacht, which was anchored in Cowes Bay.

Messages to Royal Yacht

The Prince who had already taken a deep interest in wireless telegraphy, thought that it might be possible to establish communications in this way between the yacht and Osborne house, where the Queen was staying. Marconi was approached and was naturally delighted to place his knowledge and skill at the service of the Queen. Two stations, one on board the yacht and the other at Osborne House, were soon established and in working order.

For the next 16 days, while Kemp was proceeding with his experiments at Ballycastle, Marconi was on board the Royal Yacht, sending altogether about 15O messages by wireless telegraphy. Not one of these messages had to be repeated.

The new system of wireless telegraphy attracted widespread attention and remarkable progress was made in the next few years. Before the year 1898 had run its course, messages were being sent successfully between such places as Ballycastle and Rathlin Island and between the South Foreland Ligththouse and the East Goodwin Lightship. The wireless experiments between Ballycastle and Rathlin in the summer of 1898 and extending over the months of June, Ju1y, August and early September were the first such demonstrations for Lloyds.

Eventful Summer

It was at their instance that they were conducted. The summer of 1898 must have been a particularly eventful one in the life of Ballycastle. On July 30th the town was thrown into a state of excitement by the arrival of a couple of motor cars. These had come round from Larne via Cushendall, and put up for a time at the Marine Hotel. They subsequently left for the Giant's Causeway.

Both cars had a full complement of passengers, most of whom were English tourists, who had been staying at Henry McNeill's, Ltd., Larne. During their short stay the motors were surrounded by quite a crowd, taking a lively interest in this, the first visit of a motor car to Ballycastle. The present lovely weather has attracted a considerable number of visitors and the town presents quite an animated appearance - so ran a contemporary report of the occasion.

Gottlieb Daimler thirteen years previously, patented a light high-speed two cylinder petrol engine. Later much used in motor cars, I might also add that it was in this memorable year - 1898 in Ballycastle that the Ballycastle Lawn Tennis Club held its first annual tennis tournament.

Complaints from Lloyds

The wireless experiments at Ballycastle were the outcome of complaints by Lloyds of not being able to report steamers from Torr Head, a Lloyds signalling station on the north-east corner of Ireland, and this in spite of the fact that these steamers were able to report to what is now known as Rathlin East lighthouse. Ships passed close to this lighthouse, off Altacarry Point and even in a fog they could signal their numbers, etc., by means of flags; but be this as it might, Rathlin had no means of conveying this information to Torr Head by flag signals.

"Lloyds requested me", says Kemp, "to fit a wireless station at Rathlin Lighthouse and another at Ballycastle, and I travelled on to Ballycastle at 1 p.m. on Saturday, June 4th, from which place I communicated with Lloyd's agent, Mr. Byrne, at 11 a.m. Studied the plans and surveyed the coasts of the North of Ireland and Rathlin Island. The mast at the Lighthouse was 60 feet high and 30 feet from Lloyd's hut. I left Ballycastle with Mr. Wyse and inspected Rathlin Island returning at 6.10 p.m.

Four Stages

In the course of the wireless experiments at Ba1lycastle during the summer of 1898, four stages may be noted:

Stage 1 began on Friday, June 10th, when Kemp met Mr. Hough from Lloyds in Ballycastle at 11 a.m. They arranged to experiment at the coal store, now the Pier Pavilion, with the aerial leading over the road to a small mast on top of the cliff, now the car park, almost opposite Hilsea Hotel. This mast was that appertaining to the coastguard station.

This is generally believed to have been the first wireless installation ever set up in Ireland. Next day Kemp and Hough went to Rathlin and upon their return, Kemp fitted up the station in the coalyard. The following Monday, Kemp started teaching Lloyd's agent, Mr. Byrne, and his sons, the Morse code in the hope of getting their help until Lloyds sent someone to take charge of the station.

Four days later Kemp was in Belfast where he tried, unsuccessfully as it proved, to obtain masts for the Rathlin and Ballycastle stations. On June 22nd and June 23rd, 50 Obach cells for transmission were fitted at the coalyard station at Ballycastle Quay, and 50 were fitted at the Lighthouse station on Rathlin. Mr. Byrne and his sons received further instruction from Kemp, this time in the working of the coalyard station.

Short First Stage

On 2nd July, wire and insulators arrived in Ballycastle from London "by the last train" (as Kemp describes it), and by July 5th half the wire, insulators and stores were taken to Rathlin Island and fitted up at the station there for transmission. Kemp instructed Signalman Dunovan and his two sons in the working of the station. Next day news came from London to the effect that Kemp was to take all the apparatus - "half a ton of gear," as he calls it - from Ballycastle to Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire), for the Kingstown annual regatta.

So ended Stage I - a very short-lived one - in the fitting up of the two experimental stations at Ballycastle and Rathlin. What happened at Kingstown does not concern us here, suffice it to say that the apparatus was employed to transmit reports of Kingstown Regatta to a Dublin newspaper - The Daily Express - from a steamer, "The Flying Huntress," in Dublin Bay. Mr. Marconi himself was present at these experiments - the first ever of messages being sent from sea to land by a vessel in motion.

Upon the conclusion of the regatta, Kemp and a young man named Edward Edwin Glanville, a native of Blackrock, an engineering student at Trinity College, Dublin, and employed as assistant to Marconi, set out by train from Dublin to Ballycastle. This brings us to Stage II in our story of the early wireless experiments in Ballycastle.

Aerial on Spire

Glanville was put in charge of the Rathlin Island station with instructions to transmit to Kemp at the Ballycastle end every day. "I received at various places," says Kemp in his diary, "and on the cliffs along the coast in the vicinity of Ballycastle and received the best results on an aerial connected to the Roman Catholic church spire in Ballycastle, but as there was no house or room available here - and the Company would not let me use a hut - there was not much chance to make a speedy job, as there was delay in getting spares from Belfast."

The chapel spire must then have presented a very new appearance; it had been added to the building in 1891, thanks to the John Lawless bequest, as the chapel itself dates from 1870. Kemp is at pains to state that these good results were the outcome of the courtesy and co-operation extended by the Parish Priest, the Very Rev. John Conway, V.F. Little wonder that later on in the course of the experiments - in September - when Marconi came to Ballycastle, he and Kemp showed their appreciation of this favour by calling on the Very Reverend gentleman, presumably at the parochial house on the day before they left Ballycastle for London.

Stage III in the experiments followed when Kemp managed (as he tells us) "to get the loan of a small bedroom in a lady's house on the cliff, and the loan of a jib of a crane in the pier yard (now the car park) which served me for a lowermast." This house, as Marconi subsequently explained to Kemp, belonged to Mr. Thomas Magregor Greer, M.A., T.C.D., Solicitor, Ballymoney, and now known as White Lodge, is the property and residence of Colonel H. A. Allen, D.S.O, At the time of the wireless experiments it was rented by Mr. Greer's brother-in-law, Mr. Talbot Reed, of 1, Hampstead Lane, Highgate, in the City of London.

Tragedy on Rathlin

A sad tragedy occurred on Sunday, August 27, in the course of the third stage of the experiments when Young Glanville, out for a walk on Rathlin on that afternoon accidentally fell over a cliff and was killed. This sad accident was quite unconnected with the experiments. The people on the island had often seen Glanville, who was interested in geology, climbing over the cliffs and this was no doubt the cause of the accident.

The verdict at the inquest was accidental death, but the jury, presided over by Mr. J.P. O'Kane, father of Mrs. Boylan, added the following rider - "That we beg to tender our deepest sympathy with the parents of the deceased, and also with Mr. Kemp and the other members of the staff of the Wireless Telegraph Company, with whom the deceased worked so cordially and we desire to place on record our sorrow at such a tragic ending to so promising a career, connected as it was with one of the most important discoveries of the century."

Mr. Glanville's body was taken to the mainland by the s.s. "Glentow" and from thence by rail to Dublin, for burial.

We now come to the fourth and - last stage of the early wireless experiments in Ballycastle seventy years ago almost to the day. On August 24 Kemp proceeded to erect a new mast in a field 104 feet to the top of the sprit and 104 feet from the window of a child's bedroom, which was loaned to him, at the northern side of what is now Colonel Allen's house. Thus two different bedrooms in this house were used in the course of Stage III and Stage IV of the early wireless experiments in Ballycastle.

Next day Kemp states that he finished the station and adjusted the receiver and inker. He instructed Mr. Byrne in all the details of the transmitter and requested him to follow when he received the dots and dashes from Kemp on the inker. He sent messages to, and received messages from, Mr. Byrne until 1 p.m. on that day, left the station on Rathlin in charge of Mr. Dunovan and Mr. Dunovan's two boys and returned to Ballycastle.

Satisfactory Experiments

This trip from the island to the mainland must have been something in the nature of an adventure for Kemp, as it took four hours to cross what he describes as "that very dangerous piece of water, and I caught a terrible cold." The experiments were now apparently proving very satisfactory, as next day messages were sent and received from 10 a.m. to 6.30 p.m., mostly red each way. Ten ships were reported and Lloyds' agent (Mr. Byrne) sent a report to Lloyds concerning the days’ work which had been carried out in a dense fog. The following day, August 27th, two more ships were reported to Lloyds.

The rough passage from Rathlin two days previously had evidently proved too much for Kemp, because he had to go "to bed suffering from Neuralgia and fever. The weather was very windy and wet during the day and I was forced to keep the window open - presumably the window in the child's bedroom - mentioned in the diary under August 24th - to enable me to transmit, and this increased the violent cold that I caught in the boat." Conditions were no better by August 28th. "Weather," writes Kemp, "still very wet and wind blowing a gale. I had to remain in bed, taking medicine which reduced the fever, but made me very weak."

Marconi's Arrival

Kemp must have been a somewhat sick man when next day - Monday, August 29th, the eve of the Lammas Fair - Mr. Marconi arrived in Ballycastle by the 6.15 p.m. train. One is tempted to wonder how the young scientist at 24 contemplated the scene as the narrow gauge train in which he was travelling neared its journey's end by rounding the sharp Ballylig curve, with its check rail, and passing Broombeg Wood, later replanted and now known as Ballycastle Forest, finally arrived at the Ballycastle railway terminus; the engine driver had sounded the whistle at the distant signal at Kilcraig and the train passengers surely knew that Ballycastle could not now be far off.

Was Marconi, as he made his way from the station to the Antrim Arms Hotel, almost certainly by way of the Poor Row or Station Street, interested in the stalls erected on the Diamond in readiness for the Fair next day or was he more concerned with his scientific pursuits? P.W.Paget, one of his technical assistants, has left it on record that Marconi had little interest in anything outside wireless. In any event, he may have been too deeply concerned about the death by accident of his assistant, Glanville, only a week previously to bother much about the fair. Certainly he remained indoors in the Antrim Arms Hotel all the evening.

On Lammas Fair Day

Next day - the Lammas Fair day - Kemp called up Rathlin Island station and found that they had broken their sensitive tube. "I told them," he says, "to stop for a few days. The weather was still very wet and windy and I spent the remainder of the day packing apparatus and transporting it to the Antrim Arms Hotel. I told Mr. Byrne that he would have to get a station built for carrying on further work, as the present room. i.e., the child's bedroom, must be given up because Mr. Greer of Ballymoney, the owner of the house was coming back. I tried to go to Rathlin, but found that no boat had been there since August 25th when I crossed."

On the second day of the Lammas Fair, Kemp tried to get a boat to take Marconi and himself to Rathlin, but no one would venture to cross. Instead, the scientist and his assistant went to Fair Head, whence they saw Rathlin, Torr Head, the Mull of Kintyre and the two islands at the mouth of the Clyde - Sanda and Ailsa Craig.

One of the Largest

What sort of fair was the Lammas Fair which was held during Marconi's visit to this town and some of which he must have seen, whether he was interested in what he saw of it or not? As a matter of fact it was one of the largest held in the district for years. Buyers from Belfast, Derry and Armagh and cross-channel attended, some even before the day of opening. It is believed that it would have been the most successful fair held here for years, but unfortunately at eleven o'clock and up to seven p.m. a continuous heavy downpour of rain set in and damped those attending and practically spoilt the day. The second day compensated by being gloriously fine, but the rain of the previous day acted on the attendance.

There was a great show of sheep, cattle and horses and prices were as follows -Bullocks, first class £14 to £17; second class £11 10s to £14; third class to £9 to £11; heifers, first class £12 to £16 10s; second class £€10 to £12; third class £7 to £10. Milch cows £14 to £16 and £9 to £11. Sheep from 17s 6d to 42s. A large sale was made in this class; lambs 18s to 33s; Bullocks 27s per cwt.; middling class 23s 6d per cwt.

There was a splendid show of Cushendall ponies. The Islay fish trade was most successful, ling, cod, etc., being in abundance. All the lots were sold from 3s 6d to 7s 6d a bundle. In the fruit market there was a great supply. The lots were chiefly brought by wholesale traders from Ballymena and Belfast. Such were the chief characteristics of the Ballycastle Lammas fair of seventy years ago.

Crossing to Rathlin

On Thursday, 1st September, Mr. Marconi and Kemp started from Ballycastle at 9 a.m. and crossed to Rathlin in one hour with, as Kemp describes it, "a fair wind and large sail." They visited the lighthouse, beside which the aerial mast was erected; some of the cement blocks inscribed "Lloyds" and used to hold the stays of the mast may still be seen there.

As a memorial of the early wireless experiments here, it is surely possible for one of these to be brought to Ballycastle and placed somewhere for all to see in the new promenade or municipal gardens as described in Mr. Fergus Pyle's article on "Civic Week in Ballycastle", in the "Irish Times."

Marconi and Kemp found that the ridge of Lloyds' land bore north and south and that the station at Ballycastle bore south-south-west. Kemp induced Mr. Dunovan and his sons to pack up the apparatus while he took Mr. Marconi to Ballyconagan to see the cliff where Glanville lost his life. Thus by early September, 1898, the experiments came to an abrupt end at Ballycastle. Whether or not the accidental death of Glanville on Rathlin had anything to do with this it is impossible to say.

Thanked for Co-operation

Mr. Marconi and his assistant returned to Ballycastle at 2 p.m. "pulling and sailing in 1 1/2 hours." Upon their return they visited the Very Rev. John Conway, P.P., V.F., the proprietors of the Water Mill - presumably that of Messrs. Alex. and John Nicholl, and the landowners; presumably the agent to the local estate. This was evidently to thank each of these parties for their help and co-operation during the experiments.

Next day, September 2nd, Mr. Marconi left for London and Kemp took down the mast that he had erected 104 feet north of Greer's house at the top of the Quay Hill and returned all the stores to the Antrim Arms Hotel. Six days later, on September 5th, Kemp left Ballycastle for London, - travelling via Belfast and Fleetwood.

Kemp regarded the Ballycastle experiments as very successful demonstrations in spite of the circumstance that he had to work (as he put it) under the most peculiar instructions ever given to him. In 1897 the whole of the G.P.O.'s skill was put on to a similar job, but in the case of the Ballycastle/Rathlin experiments, carried out under the auspices of Lloyds, he was sent (as he says) in that case without any assistance and complains that he had to instruct all those who helped him.

Not Until 1905

Apparently the relationships between Kemp and Lloyds were not as friendly as those between Kemp and the G.P.O. At all events the Marconi system of wireless telegraphy between Ballycastle and Rathlin was not brought into use until 1905. It replaced the parallel system which was the first system between Ballycastle and Rathlin and was, of course, quite distinct from the experiments I have described, which, as I have explained, were carried out under the auspices of Lloyds, whereas the parallel system was a purely G.P.O, affair.

Despite the somewhat adverse criticisms of Kemp in his relationship with Lloyds, the Ballycastle/Rathlin experiments must, nevertheless, have had some definite significance in the development of wireless telegraphy. Within two years, in 1900, Marconi had taken out his famous patent No. 7777 for "tuned or syntonic telegraphy."

He had transmitted signals to such a distance - over 200 miles - as to convince him that the electric waves, instead of being projected into space, as some prophets averred would be the case, would, as it were, cling to the surface of the earth, the curvature of which would, therefore, be no bar to the attainment of long ranges. Accordingly, he determined to make an attempt to send signals across the Atlantic, and for that purpose proceeded to erect a powerful station at Poldhu, in Cornwall, with a similar station at Cape Cod, in the United States of America.

Wrecked by Storm

The masts and aerial at Poldhu were wrecked by a storm in September, 1901, and though they were repaired by the end of November a similar mishap at Cape Cod threatened to delay the test for several months. To save time he went to Newfoundland and installed his instruments in a disused barracks on Signal Hill, St. John's. He had intended to support his aerial by a balloon, but as this was blown away, he substituted a kite which, with great difficulty owing to the strong wind, was kept at a height of about four hundred feet.

It had previously been arranged that at fixed times the Poldhu station should send out the signal for the letter 'S' on the Morse code - three dots - and on December 12th, 1901, both he and Kemp, using a self-restoring coherer, repeatedly heard in their telephone the three clicks which showed that the electric waves had traversed the 1,800 miles separating St. John's from Poldhu.

This momentous incident was recalled by Mr. P. W. Paget, Marconi's first technical assistant in these words - "I was with him at Signal Hill, Newfoundland, when he received the first wireless signal - the letter 'S'- ever transmitted across the Atlantic. It was from the station at Poldhu, Cornwall. He showed no excitement, calmly handing over the earphones first to Mr. George Stephen Kemp, who was also assisting him, and then to me, with the words - 'Can you hear this?' He was never unduly elated and never unduly depressed. When the twenty masts, erected at Poldhu for the Transatlantic transmission collapsed in a gale, Marconi looked at the wreckage and said quietly to me - 'Well, they will be built again.' That was all. Marconi had few hours of sleep. He had little interest in anything outside wireless.

Commercial Basis

Soon afterwards preparations were begun for the establishment of wireless telegraphy between England and America on a commercial basis. We are reminded here of those words of Longfellow:-

The heights by great men reached and kept

Were not attained by sudden flight,

But they, while their companions slept,

Were toiling upward in the night.

"At that time" (1901), wrote Marconi, "and for long afterwards, certain important sections of the technical Press in this country were against me, and spared no efforts in their determination to discredit both me and the work on long-distance wireless communication. From the first, however, 'The Times' declared its belief in me, and was swift and forceful to rebuke those who persisted in a policy of disparagement. Radio has made very great strides since 1901, and yet I often look back to those early days and remember with deep gratitude what a wonderful encouragement of support it was to me to know that a great newspaper like 'The Times' had faith in me. Even as regards my work relating to the utilization of electric waves for world wide communication."

In the words of his contemporary, Rudyard Kipling, Marconi was one of those who could "meet with triumph and disaster and treat those two imposters just the same."

Retained Vigour of Youth

To the end of his life Marconi retained the vigour of youth, which was also apparent in his personal appearance. He died on 20th July, 1937 at the age of sixty-three. Kemp pre deceased him by four years. Marconi described Kemp as his first assistant, collaborator and friend, and would always be regarded as a pioneer of the wonderful science of wireless telegraphy.

When Marconi was about to be admitted to the honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law in the University of Oxford, he was referred to as " the magician who found a means of transmitting signals from shore to shore and from ship to ship."

Granted that the association of this locality with wireless telegraphy in its infancy is due entirely to the first demonstration for Lloyds so as to facilitate shipping, may have been of little significance, as compared, let us say, with the Poldhu - Newfoundland transmissions, nevertheless, Kemp's installation of apparatus in Ballycastle in June, 1898 - apparatus that would have included a Righi spark gap and an induction coil, a Morse inker and relays - was almost certainly the first of its kind in Ireland. It is true that Preece was already conducting his own experiments with wireless by the induction method, which made use of long parallel wires, and that subsequently such a method was established between Ballycastle and Rathlin and was a purely Post Office affair. The service (sparking coil, coherer, etc.) established in 1898 at the request of Lloyd's Shipping Agency terminated - it would appear rather abruptly – in September 1898 because of objections on the part of the Post Office authorities. Post Office engineers carried out tests of their own by an induction method. This involved a heavy gauge wire carried on poles and down into the sea at Murlough Bay. In 1905 or 1906 the Marconi Company was again asked to install its system because, by that time, it had overcome opposition and was well established. But be all this as it may, the Ballycastle - Rathlin trials undoubtedly stand out in the history of wireless communication and in states unborn and accents yet unknown, wireless discoveries and developments will still be broadening their influence upon the lives of men.