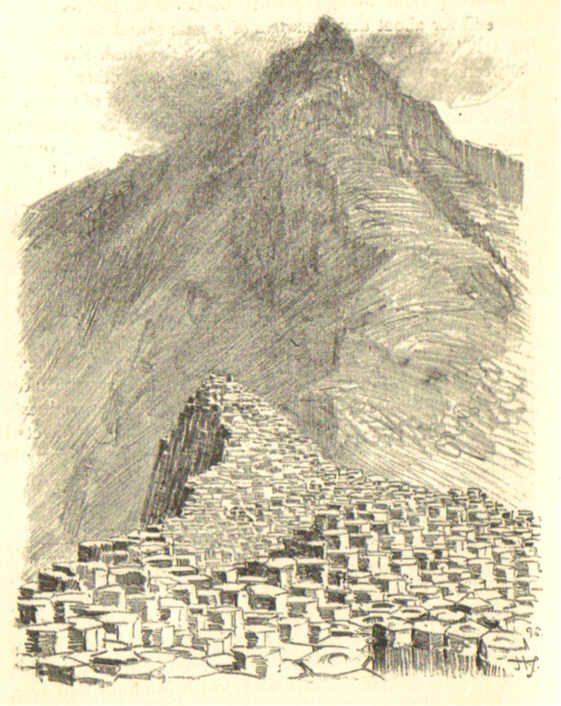

Causeway and the Giant's Chimney Tops.

Highways & Byways in Donegal and Antrim

by Stephen Gwynn with illustrations by Hugh Thompson

CHAPTER XVI

ONCE the tourist is across the Foyle, he lands in a very different country from any that he has travelled in Donegal. All through Tyrconnell, there is no history to write except that of the Gael — a history that stops short with the Flight of the Earls in 1607. But in those days, the history of Eastern Ulster — the Protestant North — was only beginning ; and the unhappy religious strife which has played, and has still to play so great a part in the history of this new Ireland of mixed blood always found its main theatre in Derry and Antrim. So, from this point onwards, I can make no attempt to exhaust the historic associations of the route : besides Antrim is not my own county, and of it I must write merely as a tourist for tourists.

If you had been crossing Lough Foyle in 1600, you would have left the O'Doherty's country of Inishowen — always disputed between O'Neill and O'Donnell — to come into the O'Cahan's or O’Kane's. O'Cahan, whose chief seat was at Limavady, was the principal urraght of O'Neill; his country included all between the Foyle and the Bann ; and when an O'Neill was proclaimed at Tullaghogue it was the proud function of the O'Cahan to toss a shoe over his head. In 1600 the only trace of the English was the establishment of forts at Culmore and Derry by Sir Henry Docwra, which it seemed little likely they would hold good. Twenty years later the new order was established. Sir Cahir O'Doherty had rebelled and Chichester was lord of his land in Inishowen. Tyrone had fallen ; in his forfeiture the O'Cahan had been involved ; and the whole country had been made over to twelve London companies — a grant of nearly 40,000 acres to 119 families. It was a black day for the native Irish; but it must be allowed that the new comers brought with them the arts of peace; and the flax industry, which gave to Ulster what was once its most important crop, and which is still the predominant industry of its thriving towns, dates from the English settlement.

East of the Bann begins the great Coast Road, down which you will travel, and this country of the Glens escaped " plantation " and therefore remains comparatively Celtic in character. When the O'Donnells and O'Neills went under, the third great house of Ulster, the Macdonnells, escaped, and were taken into high favour by James I., thanks to their Scotch blood. Randal Macdonnell was created Earl of Antrim and received a grant of the Glens and the Route, from the Curran of Larne to the Cutts of Coleraine. Yet, although this coastward strip from the neighbourhood of Coleraine to Larne has never been violently converted into the home of a Saxon and Protestant population, and remains largely Gaelic and Catholic, there has been much infiltration from the planted districts.

The district also has for a long time been well known. Its natural curiosities in the strange forms of basalt rock, culminating in the marvel of the Causeway, attracted attention in days when mere grandeur of cliff scenery was counted repellent. For, bold as the coast is, it is tame after that of Donegal. Instead of granite you have chalk, and red sandstone, which give delightful colour, but have not the sombre beauty of Slieve League and Horn Head, even if they had equal height; and the basalt even in the mass of Fair Head inevitably suggests the hand of some artificer. A more scientific account of the matter is supplied to me by a friend who writes :

" The surface of Antrim is mostly trap ; this rests on beds of indurated chalk, below which is a stratum of greenstone. The next stratum is new red sandstone, and the lowest bed is mica slate. The trap rises on both sides of the Bann, and the whole field shows the same scarped features and succession of strata towards the Roe river in Derry from the Atlantic, North Channel and Belfast Lough. It is this succession of strata which gives the peculiar charm to the coast scenery of Antrim. At the Causeway and eastward to Fair Head the trap assumes a crystalline character, descending to the sea in the vast masses of basaltic columns for which this part of the coast is famous."

But the most marked difference in the scenery lies in the seaward horizon. In Donegal you look out north and west, and the knowledge that no land lies within a thousand miles either way adds to your sense of vastness. The Antrim coast depends for its chief beauty on the fact that it makes one side of a narrow seaway. The Scotch hills, receding or approaching as the clouds lift or thicken, sometimes invisible, sometimes flashing into incredible distinctness, give a fascination to travel that keeps your attention continually on the stretch. And, historically, you are forced to see that the essential fact about Donegal is its remoteness from Great Britain, whereas the whole history of Antrim has been determined by the easy access from shore to shore afforded by this narrow and harbourable sea.

Commerce there was from the earliest times, for men were bold enough to cross the Moyle — as it is called in Antrim — in curraghs. But it was in the second century after Christ that Reuda or Riada, with a following of Ulstermen, made a settlement among the Picts, and founded the principality called Dal Riada, with a share on each shore. The Route, which is the local name for Antrim, north of the Glens — that is from Ballycastle to the Bann — is called after this Reuda. In 503, a Christian colony, under the northern branch of the Hy-Niall, absorbed the older settlement; Fergus, its chief leader, was the ancestor of the Kings of Scotland, and in the days when Columba was Abbot of Iona, the Scotch colony gained recognition as a separate kingdom. From this branch of the Hy-Niall descend the Macdonnells, who in the fifteenth century returned from Alba and gradually conquered for themselves a holding on the Irish coast.

You will have to go up as far as Coleraine to cross the Bann, and it is worth going up into the town for a very beautiful view inland up the course of the river. Coleraine is itself one of the main centres of what Roman Catholics call the Black North — a great Presbyterian stronghold. The Scotch element in these northern places preserves a number of valuable traditions — one is of skill in baking. Derry, and still more Coleraine, abound in all sorts of fancy bread, excellent in quality, and far superior to any that can be got in Dublin. Local usages run strong in these places, and receipts are handed down in their integrity from father to son, from mother to daughter. So by all means stop for lunch in Coleraine and explore the pastry-cook's in the Diamond. Another famous product of Coleraine used to be its whisky, and I can well remember in Donegal to have heard the priest of our parish come up to my father and express his delight at hearing that there had been a sermon against the drink. " Sure, I'm for ever at them about it," he said. " An' it's the bad stuff they take that does the worst of the mischief," he added. " I told them from the altar that I never touch a drop myself but the best Coleraine." And a friend of mine has often told me how in his undergraduate days, when whisky was still practically unknown across the water, in what would then have been called genteel circles, he took with him to Cambridge a gallon jar of Coleraine. The result was an immediate conversion of the entire college to the new spirit, and a sudden demand for whisky upon merchants not a little shocked by such an access of vulgarity.

These are the modern interests of the town; but it has a history too. St. Patrick having arrived in the neighbourhood, was offered a site for a church, and he chose a spot overgrown with ferns which some boys were then clearing. So was founded the church which came to be known as Coolrathen "the ferny corner." Columba visited it in 590, and from that date up till 1122, we have records of the names of abbots who ruled the priory there. In 1213, the English destroyed the monastery. Later on, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when the Scots began to settle on the Antrim coast, Coleraine was the scene of battles between the Macdonnells and O'Neills. In 1613, the whole of O'Kane's country was granted to London Companies, and from that time dates Coleraine's importance, though Coleraine itself came within the grant made to the Macdonnells. The salmon fishing on the Bann was taken away from the Earls of Antrim, and became a lucrative source of revenue to English proprietors ; though not so valuable as it is in these days of quick transport. Old men can remember a time when servants in this neighbourhood used to stipulate that they should not be asked to eat salmon more than four days a week !

The populous English colony was, of course, an object of attack in times of rebellion. Coleraine stood a siege in 1641, and again in 1689 ; on the latter occasion, the garrison were driven out and had to throw themselves into Derry. But upon the whole, it is unlikely that any tourist with the Antrim coast before him will care to stop in this prosperous little linen-making town; and I do not care to enlarge upon its history, as it would bring one into a discussion of that modern life of Anglicised Ireland, which has so little affected the wild sea coasts round which the route of our sketching is laid.

Highways & Byways in Donegal and Antrim

by Stephen Gwynn with illustrations by Hugh Thompson

CHAPTER XVI

ONCE the tourist is across the Foyle, he lands in a very different country from any that he has travelled in Donegal. All through Tyrconnell, there is no history to write except that of the Gael — a history that stops short with the Flight of the Earls in 1607. But in those days, the history of Eastern Ulster — the Protestant North — was only beginning ; and the unhappy religious strife which has played, and has still to play so great a part in the history of this new Ireland of mixed blood always found its main theatre in Derry and Antrim. So, from this point onwards, I can make no attempt to exhaust the historic associations of the route : besides Antrim is not my own county, and of it I must write merely as a tourist for tourists.

If you had been crossing Lough Foyle in 1600, you would have left the O'Doherty's country of Inishowen — always disputed between O'Neill and O'Donnell — to come into the O'Cahan's or O’Kane's. O'Cahan, whose chief seat was at Limavady, was the principal urraght of O'Neill; his country included all between the Foyle and the Bann ; and when an O'Neill was proclaimed at Tullaghogue it was the proud function of the O'Cahan to toss a shoe over his head. In 1600 the only trace of the English was the establishment of forts at Culmore and Derry by Sir Henry Docwra, which it seemed little likely they would hold good. Twenty years later the new order was established. Sir Cahir O'Doherty had rebelled and Chichester was lord of his land in Inishowen. Tyrone had fallen ; in his forfeiture the O'Cahan had been involved ; and the whole country had been made over to twelve London companies — a grant of nearly 40,000 acres to 119 families. It was a black day for the native Irish; but it must be allowed that the new comers brought with them the arts of peace; and the flax industry, which gave to Ulster what was once its most important crop, and which is still the predominant industry of its thriving towns, dates from the English settlement.

East of the Bann begins the great Coast Road, down which you will travel, and this country of the Glens escaped " plantation " and therefore remains comparatively Celtic in character. When the O'Donnells and O'Neills went under, the third great house of Ulster, the Macdonnells, escaped, and were taken into high favour by James I., thanks to their Scotch blood. Randal Macdonnell was created Earl of Antrim and received a grant of the Glens and the Route, from the Curran of Larne to the Cutts of Coleraine. Yet, although this coastward strip from the neighbourhood of Coleraine to Larne has never been violently converted into the home of a Saxon and Protestant population, and remains largely Gaelic and Catholic, there has been much infiltration from the planted districts.

The district also has for a long time been well known. Its natural curiosities in the strange forms of basalt rock, culminating in the marvel of the Causeway, attracted attention in days when mere grandeur of cliff scenery was counted repellent. For, bold as the coast is, it is tame after that of Donegal. Instead of granite you have chalk, and red sandstone, which give delightful colour, but have not the sombre beauty of Slieve League and Horn Head, even if they had equal height; and the basalt even in the mass of Fair Head inevitably suggests the hand of some artificer. A more scientific account of the matter is supplied to me by a friend who writes :

" The surface of Antrim is mostly trap ; this rests on beds of indurated chalk, below which is a stratum of greenstone. The next stratum is new red sandstone, and the lowest bed is mica slate. The trap rises on both sides of the Bann, and the whole field shows the same scarped features and succession of strata towards the Roe river in Derry from the Atlantic, North Channel and Belfast Lough. It is this succession of strata which gives the peculiar charm to the coast scenery of Antrim. At the Causeway and eastward to Fair Head the trap assumes a crystalline character, descending to the sea in the vast masses of basaltic columns for which this part of the coast is famous."

But the most marked difference in the scenery lies in the seaward horizon. In Donegal you look out north and west, and the knowledge that no land lies within a thousand miles either way adds to your sense of vastness. The Antrim coast depends for its chief beauty on the fact that it makes one side of a narrow seaway. The Scotch hills, receding or approaching as the clouds lift or thicken, sometimes invisible, sometimes flashing into incredible distinctness, give a fascination to travel that keeps your attention continually on the stretch. And, historically, you are forced to see that the essential fact about Donegal is its remoteness from Great Britain, whereas the whole history of Antrim has been determined by the easy access from shore to shore afforded by this narrow and harbourable sea.

Commerce there was from the earliest times, for men were bold enough to cross the Moyle — as it is called in Antrim — in curraghs. But it was in the second century after Christ that Reuda or Riada, with a following of Ulstermen, made a settlement among the Picts, and founded the principality called Dal Riada, with a share on each shore. The Route, which is the local name for Antrim, north of the Glens — that is from Ballycastle to the Bann — is called after this Reuda. In 503, a Christian colony, under the northern branch of the Hy-Niall, absorbed the older settlement; Fergus, its chief leader, was the ancestor of the Kings of Scotland, and in the days when Columba was Abbot of Iona, the Scotch colony gained recognition as a separate kingdom. From this branch of the Hy-Niall descend the Macdonnells, who in the fifteenth century returned from Alba and gradually conquered for themselves a holding on the Irish coast.

You will have to go up as far as Coleraine to cross the Bann, and it is worth going up into the town for a very beautiful view inland up the course of the river. Coleraine is itself one of the main centres of what Roman Catholics call the Black North — a great Presbyterian stronghold. The Scotch element in these northern places preserves a number of valuable traditions — one is of skill in baking. Derry, and still more Coleraine, abound in all sorts of fancy bread, excellent in quality, and far superior to any that can be got in Dublin. Local usages run strong in these places, and receipts are handed down in their integrity from father to son, from mother to daughter. So by all means stop for lunch in Coleraine and explore the pastry-cook's in the Diamond. Another famous product of Coleraine used to be its whisky, and I can well remember in Donegal to have heard the priest of our parish come up to my father and express his delight at hearing that there had been a sermon against the drink. " Sure, I'm for ever at them about it," he said. " An' it's the bad stuff they take that does the worst of the mischief," he added. " I told them from the altar that I never touch a drop myself but the best Coleraine." And a friend of mine has often told me how in his undergraduate days, when whisky was still practically unknown across the water, in what would then have been called genteel circles, he took with him to Cambridge a gallon jar of Coleraine. The result was an immediate conversion of the entire college to the new spirit, and a sudden demand for whisky upon merchants not a little shocked by such an access of vulgarity.

These are the modern interests of the town; but it has a history too. St. Patrick having arrived in the neighbourhood, was offered a site for a church, and he chose a spot overgrown with ferns which some boys were then clearing. So was founded the church which came to be known as Coolrathen "the ferny corner." Columba visited it in 590, and from that date up till 1122, we have records of the names of abbots who ruled the priory there. In 1213, the English destroyed the monastery. Later on, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when the Scots began to settle on the Antrim coast, Coleraine was the scene of battles between the Macdonnells and O'Neills. In 1613, the whole of O'Kane's country was granted to London Companies, and from that time dates Coleraine's importance, though Coleraine itself came within the grant made to the Macdonnells. The salmon fishing on the Bann was taken away from the Earls of Antrim, and became a lucrative source of revenue to English proprietors ; though not so valuable as it is in these days of quick transport. Old men can remember a time when servants in this neighbourhood used to stipulate that they should not be asked to eat salmon more than four days a week !

The populous English colony was, of course, an object of attack in times of rebellion. Coleraine stood a siege in 1641, and again in 1689 ; on the latter occasion, the garrison were driven out and had to throw themselves into Derry. But upon the whole, it is unlikely that any tourist with the Antrim coast before him will care to stop in this prosperous little linen-making town; and I do not care to enlarge upon its history, as it would bring one into a discussion of that modern life of Anglicised Ireland, which has so little affected the wild sea coasts round which the route of our sketching is laid.

The Causeway

Go out from Coleraine then by the road that leads to Portstewart, past Agherton churchyard and rectory — any one will direct you — and you will have a last pleasant glimpse of the Bann running seawards ; a little further along, you are across the headland that runs out to the Bann mouth ; Portstewart and the sand-hills are close on your left. A road turning to the left, about a quarter of a mile beyond Agherton rectory, will take you into the middle of them. From these sand-hills a road of about a mile long leads into Portstewart, running just inside of a low line of cliffs. Before you reach the town itself, you pass on your left a big modern building, Portstewart Castle; and as you ride along the trim quay, with its row of houses, advertising lodgings to let, you will note one called Lever Cottage. That is where Harry Lorrequer was written. Lever was dispensary doctor at Portstewart in 1837, when his first book began to appear in the Dublin University Magazine. In these days, W. H. Maxwell, author of Stories of Waterloo, and other soldiering books, lived at Portrush ; the two men were close friends, and no doubt Maxwell's talk inspired Lever's early tales of Peninsular campaigning. Another man of letters lived at Portstewart in the last century, but born to a very different distinction from Lever's. This was Adam Clarke, who acquired a certain fame as a biblical commentator.

From Portstewart, you have a road of three miles running along the sea to Portrush : and upon a fine day you have continuously a view of the Inishowen headlands across the mouth of Lough Foyle. If the weather is clear, Islay is to be seen on the horizon. On the left of the road, just inside a great stack of rock which rises from the sea, is a fragment of the ruins of Ballyreagh Castle, or, as it was formerly called, Dunferte, a fortress of the O'Kanes which Sir John Perrot took in 1584.

A little rise brings you to the brow above Portrush and you run down into that prosperous little haven on this very harbourless coast. Golf has done Portrush a good turn, for the links there are accounted, on the whole, the best in Ireland, and very pretty links they are, even for a sane man or woman to travel over. For the golfer, it seems, they are a paradise — but a paradise which contains a Purgatory — that is the name they give to one famous bunker which, upon a day of golfing, is full of gnashing of teeth. Outside the links, close in to the pleasant-looking beach, lie the Skerries, a range of rocky islets ; and along the road which passes the links runs the electric tramway to the Giant's Causeway, a way paved with contention. The low rail along which runs the electric current — conveyed to the machinery of the cars by a contact with brushes which rub its surface — is exposed by the roadside : and according to the neighbourhood has been the cause of fatal accidents to man and beast. According to the supporters of the company, it was the practice of the natives if they possessed a horse or cow in articulo mortis, to take it and place it leaning against the electric rail; not in hope to galvanise the moribund, but in order that it might die there and compensation be exacted from the company. On which side the truth lay I have never discovered, but in the meanwhile it will be just as well not to sit on this rail.

You will follow the line of this tramway from Portrush — and at the time when I travelled the road a very bad line I found it — and sweeping round the point you come in full view of the White Rocks and Dunluce. The White Rocks are a range of chalk cliffs ranging from fifty to a hundred and fifty feet in height in a semicircle around the bay: in front of them is the bright sand with its border of breaking waves, which on most days come in slowly rolling one after the other in moving curves cresting higher and higher till they touch the sand, when the marbled surface begins to show more white, and suddenly they are shattered and creep up the beach in foam. In the cliffs are caves, if you like to go down and visit them ; and you will see, as you ride along, the Giant's Head, a curious face formed by the jutting angle of one of these cliff fronts. Dunluce stands on a black projection of basalt beyond the range of the chalk, and even from that distance you can get a fair idea of its surprising extent. But you must visit it: and to that end you ride on till a narrow cart track — for it is no better — turns up to the left, while on the right you have the ruins of the old chapel which, from, its peaceful character, did not need to be enclosed in the ring of fortifications. This castle was the chief fortress of the Antrim Macdonnells, of whom some brief account must here be given.

From Eoghad of the Hy Niall and his wife Aileach, daughter of the King of Alba — the princess for whom was built the Grianan of Aileach, looking over Lough Swilly — sprang a numerous family. Two of her sons founded the Dalriadic kingdom, with a foot on either shore of the Moyle, which early in the sixth century was consolidated by Fergus Mac Erc — the prince who on one of his journeys between the shores of Antrim and Cantire was driven out of his course by wind and lost on the rock which still keeps his name, Carrickfergus — the Rock of Fergus. By the end of the sixth century the Scotch kingdom — the Lordship of the Isles — was recognised as distinct and independent; and when the Macdonnells came to Ireland, as they did countless times between the sixth and fourteenth centuries, they came either as allies or enemies. In 1211, for instance, they spoiled Derry, but it was as the allies of the O'Donnells of Tyrconnell. They were not then known as Macdonnells. Donnell, the chief from whom the Clandonnell took its name, was Lord of the Isles about 1250. Their stepping stone to the Irish coast was Rathlin, which belonged to them in the days of Robert Bruce, whom Angus Og Macdonnell sheltered there in 1306. This Angus made a further step into Ireland, for he married an O'Kane and took for her dowry seven score men of all the names in O'Kane's country, that he might settle them on his lands in Cantire. Another marriage alliance of great moment was contracted by a later Macdonnell with Marjory Bisset, daughter of a Norman family, who originally settled in Scotland. But the Bissets being in trouble for slaying the Earl of Galloway, fled across to the Antrim coast, and there seized and held an estate in the Southern Glens, which came with Marjory to her husband. But the foundation of the Macdonnell power in Antrim dates from Alexander or Alastar Macdonnell, who about 1500 occupied a position on the north of Ballycastle Bay, and built there his stronghold of Duneynie. Under it lay Port Brittas, where there was easy landing for his galleys when they ran across from his lordship in Cantire. The Lordship of the Isles was now by law a thing of the past, but the Macdonnells were insubordinate vassals of the Scottish crown; and as their foothold on the Scotch coast grew less secure — and indeed from 1500 they were practically outlawed in Scotland — so they strengthened themselves on the Antrim shore. Alastar Macdonnell had six sons. James, the eldest brother, married Lady Agnes Campbell, the daughter of the third Earl of Argyll, thus for a moment reconciling two bitterly hostile houses. Moreover, though it was now treason to bear the title, he was elected Lord of the Isles. His lands in Antrim centred round Glenarm, which had come to Clandonnell as the heritage of Marjory Bisset. His brothers set themselves to extend their power northward into the Route, which was then defined as what lay between the Bush and the Bann on the shore, and between the Bann and the Glens inland. Colla Macdonnell, third of the brothers, built Kenbane Castle, whose ruins may still be seen about two miles west of Ballycastle. But he did better than that. The lords of the Route were the MacQuillins, a Norman family settled in Ireland : whether the name represents Mac Hugolin or Mac Llewellyn is disputed, but up to the days of Shane O'Neill it was recognised that the MacQuillin (it is commonly Anglicised McWilliam) was an "Englishman." MacQuillin was naturally at war with the O'Kane, for their lands marched at the Bann : and Colla brought his army of redshanks to help MacQuillin, and was victorious. Whether by MacQuillin's gratitude, or, as is more likely,

by his own imperious claim for bonachta — free quarters for his soldiery — he and his men wintered in Dunluce, and he married Eveleen MacQuillin. But little peace came of the alliance, and there were pitched battles between the clans. The final issue began to be fought out at Ballycastle, and was finished on the second day at Slieve-an-Aura, up in Glen Shesk. The MacQuillins were totally defeated, and James Macdonnell made Colla Lord of the Route and Constable of Dunluce. Colla died in 1558, and was succeeded by the most famous of these Macdonnell fighters, Sorley Boy Macdonnell.

Sorley is, Anglicised, Charles, but in reality it is an old Gaelic name, and was borne by Sorley's ancestor Somhairle or Somerled, who defended his lands in Argyll so strongly against the Danes in the eighth century. But Sorley Boy in Irish state papers is Carolus Flavus — yellow-haired Charles — and there is no want of mention of him. He was born in 1505 and lived till 1590 — a warrior till well past eighty. When Sorley became Lord of the Route in 1558, there were hard days for the Macdonnells. The English from 1530 onwards had become anxious to drive out these swarms of Scotch-Irish who poured in year by year; and in Ulster itself there was the redoubtable Shane O'Neill determined to be lord paramount in the north. In 1563 Shane made peace with Elizabeth and turned on the Clandonnell. In 1564 he defeated them in a skirmish at Coleraine, and in 1565 utterly routed them at Ballycastle and took both Sorley and James, head of the clan. Marching northward, he came to Dunluce, which baffled him; but holding Sorley, he held the key of its gates, and swore to starve the chief if he were not given admission. So on that day Dunluce was surrendered. James Macdonnell died in prison and Sorley became head of the Irish branch of the clan. In 1567 he was released from captivity by the bloody death of Shane O'Neill, who, being defeated by O'Donnell and hemmed in, turned to the Scots for help but was hacked to pieces at Cushendun. His death left the Macdonnells directly face to face with the English. Nevertheless there were not open hostilities at once. Elizabeth recognised Sorley as Lord of the Route and sent him a patent for his estates. But Sorley, receiving the parchment in Dunluce, swore that what had been won by the sword should never be kept by the sheepskin, and burnt the document before his retainers. In 1571 Walter, Earl of Essex, set out to colonise Ulster, and by way of a lesson in civilisation invited the O'Neill chieftains to a banquet, and treacherously slaughtered them. What measure he dealt to Sorley Boy's women and children in Rathlin you shall read elsewhere, but the Macdonnell chief was no more to be cowed by this butchery than on the day when they showed him his son's head on the gate of Dublin castle. "My son," he retorted, "has many heads." In 1584 Sir John Perrot marched into Ulster, and brought cannon against Dunluce that shook it sadly till it was forced to surrender. Sorley was not taken in it, and in the next year he re-captured it by treachery; but the triumphant Tudor bastard struck fear into him, and the old chief, now eighty years old, came to Dublin and there made his allegiance duly to Queen Elizabeth's portrait, going on his knees to kiss the embroidered "pantofle" of her Majesty's royal foot. He died in 1590 at his castle of Duneynie, and was buried among his kin at Bonamargy Abbey, in Ballycastle. His son, Sir James Macdonnell, succeeded him as Constable of Dunluce, but died in 1601; Sir Randal, another son of Sorley's, fortified Dunluce in defiance of orders, and joined O'Neill and Red Hugh in their rebellion; but after the defeat at Kinsale, seeing the game was up, he made timely profession of loyalty and was taken into favour by James, who granted him formally all the land from the Cutts of Coleraine to the Curran of Larne. Macdonnell remained staunch and was rewarded in 1620 with the earldom of Antrim. He died at Dunluce in 1639. His son, the second earl, had for mother Tyrone's daughter, and so was an object of suspicion, though he lived at Charles I's court and married Buckingham's widow. In 1641 came the rebellion, and a Macdonnell — the Earl's cousin — was prominent among the rebel leaders. Antrim seems to have wavered between his loyalty and a natural feeling for those who were fighting to recover the lands from which they or their fathers had been ejected. But he relieved the garrison of Coleraine and gave a hospitable welcome to General Munro in Dunluce. That officer accepted the hospitality, then seized his host and imprisoned him on suspicion in Carrickfergus. Antrim escaped, and appealed to the King; returned and was again taken by Munro, but again escaped and joined Owen Roe O'Neill, and fought strenuously for the King. Under the Commonwealth he was deprived of his estates, but like the other " innocent Papists " received an allotment in Connaught, whither the Celts, under Cromwell's policy, were being driven as if into a pen. Under the Restoration he obtained, after much difficulty, restitution of his own. But Dunluce by this time had fallen into useless ruins, and the Earl built Ballymagarry House near it as a residence. Earlier than that the castle had begun to crumble, for in 1639, when Antrim's wife, the Marchioness of Buckingham, was entertaining a great party, an outlying piece of the wall overhanging the landward mouth of the cave fell, carrying eight servants in its ruins. It was probably after this that the buildings on the near side of the chasm were erected.

Thus Dunluce has been only a picturesque accessory of the Macdonnell possessions since the Commonwealth, and not a place of strength. The later history of the family may be briefly sketched. The third Earl, like his father, was unable to take a decided part when the troubles came in 1689 : marching to the relief of Derry, he was shut out by its defenders and suffered forfeiture, but regained his estates after much petitioning. The fourth Earl in 1715 was likewise suspected of Jacobite leanings, and threatened with forfeiture. With the death of the sixth Earl in 1791 the male heirs became extinct, and the present holders of the title trace their descent through the female side. The family seat is at Glenarm, which came to the Macdonnells in the inheritance of Marjory Bisset.

I borrow a description of Dunluce Castle, as it is at present, from Mr. Cooke's Handbook.

" It is built on a projecting rock, separated from the mainland by a deep chasm about twenty feet wide, which is bridged over by a single arch about two feet broad, the only approach to the castle . . . Its exact date is not known, but it was erected by the McQuillins, probably early in the 16th century. A small enclosed courtyard is first reached, and at the lower end is a square tower, the barbican, in which is the main entrance door. From this a strong wall about seventy feet long runs along the edge of the cliff to McQuillin's Tower, circular, the walls of which are eight feet thick and contain a small staircase reaching to the summit. About twenty yards north is Queen Meave's Tower, and the connection between them has given way. At the northern extremity are the remains of the kitchen which fell, overhanging the mouth of the cave."

The castle has been made by Mr. Frank Mathew the scene of a very picturesque romance of Elizabethan times — Spanish Wine — in which, however, he invents passages communicating from above with the sea way into the cave which never have existed — probably because it is only of an odd time that boats dare enter that perilous passage.

Two other things of interest should be noted about Dunluce. The wreck of the Gerona at Port-na-Spania has been already recounted. From the wreck Sorley Boy recovered three brass guns, which were promptly claimed by Government. But Sorley refused resolutely to give them up — it must have been nearly his last act — and in 1597, when his son Randal fortified Dunluce it was on this ordnance that he largely relied. Also in 1584, when Sir John Perrot took the place, he carried away among the spoil "Holy Columbkille's cross," a relic which he sent to Burghley as being " a god of great veneration to Sorley Boy and all Ulster," though of little price for its jewels — which probably were only rock-crystals. What became of the cross no one knows ; it may some day be unearthed in some old house.

The bridge at Dunluce has really no great terrors ; it is fairly wide and the drop is not big. But it is a convenient test of your fitness to go over Carrick-a-rede, for if you feel the least nervousness at Dunluce, the wider a berth you give to Carrick-a-rede the better. The last thing to be done is either by boat or land to visit the cave, and indeed it is well worth while to do both. On the landward side of the round cliff on which stands the castle, the cave begins in a great hole like the burrow of some gigantic badger; you go down a dusty and stony path into it, and at the bottom, the salt smell of ocean gathered up in this funnel strikes you suddenly. The cave is a long tunnel not above ten yards across, and narrowing towards the exit a hundred yards away. As you stand by the water's edge — or near it, for this is a thing to be done with discretion, waves being capricious, incalculable things — looking back you see the meeting of two lights, the landward, which comes in pinkish over the stones, and the colder light reflected in from off the sea face. Overhead is a strangely regular roof with a strong resemblance to the groining that one sees in Jacobean work : and on each side springs the arch upon which rock and castle rest, with its marvellous architecture of buttresses. It is indeed a scene that might inspire a master builder.

Go out from Coleraine then by the road that leads to Portstewart, past Agherton churchyard and rectory — any one will direct you — and you will have a last pleasant glimpse of the Bann running seawards ; a little further along, you are across the headland that runs out to the Bann mouth ; Portstewart and the sand-hills are close on your left. A road turning to the left, about a quarter of a mile beyond Agherton rectory, will take you into the middle of them. From these sand-hills a road of about a mile long leads into Portstewart, running just inside of a low line of cliffs. Before you reach the town itself, you pass on your left a big modern building, Portstewart Castle; and as you ride along the trim quay, with its row of houses, advertising lodgings to let, you will note one called Lever Cottage. That is where Harry Lorrequer was written. Lever was dispensary doctor at Portstewart in 1837, when his first book began to appear in the Dublin University Magazine. In these days, W. H. Maxwell, author of Stories of Waterloo, and other soldiering books, lived at Portrush ; the two men were close friends, and no doubt Maxwell's talk inspired Lever's early tales of Peninsular campaigning. Another man of letters lived at Portstewart in the last century, but born to a very different distinction from Lever's. This was Adam Clarke, who acquired a certain fame as a biblical commentator.

From Portstewart, you have a road of three miles running along the sea to Portrush : and upon a fine day you have continuously a view of the Inishowen headlands across the mouth of Lough Foyle. If the weather is clear, Islay is to be seen on the horizon. On the left of the road, just inside a great stack of rock which rises from the sea, is a fragment of the ruins of Ballyreagh Castle, or, as it was formerly called, Dunferte, a fortress of the O'Kanes which Sir John Perrot took in 1584.

A little rise brings you to the brow above Portrush and you run down into that prosperous little haven on this very harbourless coast. Golf has done Portrush a good turn, for the links there are accounted, on the whole, the best in Ireland, and very pretty links they are, even for a sane man or woman to travel over. For the golfer, it seems, they are a paradise — but a paradise which contains a Purgatory — that is the name they give to one famous bunker which, upon a day of golfing, is full of gnashing of teeth. Outside the links, close in to the pleasant-looking beach, lie the Skerries, a range of rocky islets ; and along the road which passes the links runs the electric tramway to the Giant's Causeway, a way paved with contention. The low rail along which runs the electric current — conveyed to the machinery of the cars by a contact with brushes which rub its surface — is exposed by the roadside : and according to the neighbourhood has been the cause of fatal accidents to man and beast. According to the supporters of the company, it was the practice of the natives if they possessed a horse or cow in articulo mortis, to take it and place it leaning against the electric rail; not in hope to galvanise the moribund, but in order that it might die there and compensation be exacted from the company. On which side the truth lay I have never discovered, but in the meanwhile it will be just as well not to sit on this rail.

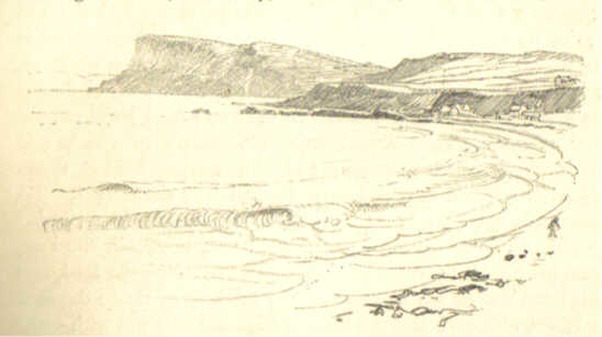

You will follow the line of this tramway from Portrush — and at the time when I travelled the road a very bad line I found it — and sweeping round the point you come in full view of the White Rocks and Dunluce. The White Rocks are a range of chalk cliffs ranging from fifty to a hundred and fifty feet in height in a semicircle around the bay: in front of them is the bright sand with its border of breaking waves, which on most days come in slowly rolling one after the other in moving curves cresting higher and higher till they touch the sand, when the marbled surface begins to show more white, and suddenly they are shattered and creep up the beach in foam. In the cliffs are caves, if you like to go down and visit them ; and you will see, as you ride along, the Giant's Head, a curious face formed by the jutting angle of one of these cliff fronts. Dunluce stands on a black projection of basalt beyond the range of the chalk, and even from that distance you can get a fair idea of its surprising extent. But you must visit it: and to that end you ride on till a narrow cart track — for it is no better — turns up to the left, while on the right you have the ruins of the old chapel which, from, its peaceful character, did not need to be enclosed in the ring of fortifications. This castle was the chief fortress of the Antrim Macdonnells, of whom some brief account must here be given.

From Eoghad of the Hy Niall and his wife Aileach, daughter of the King of Alba — the princess for whom was built the Grianan of Aileach, looking over Lough Swilly — sprang a numerous family. Two of her sons founded the Dalriadic kingdom, with a foot on either shore of the Moyle, which early in the sixth century was consolidated by Fergus Mac Erc — the prince who on one of his journeys between the shores of Antrim and Cantire was driven out of his course by wind and lost on the rock which still keeps his name, Carrickfergus — the Rock of Fergus. By the end of the sixth century the Scotch kingdom — the Lordship of the Isles — was recognised as distinct and independent; and when the Macdonnells came to Ireland, as they did countless times between the sixth and fourteenth centuries, they came either as allies or enemies. In 1211, for instance, they spoiled Derry, but it was as the allies of the O'Donnells of Tyrconnell. They were not then known as Macdonnells. Donnell, the chief from whom the Clandonnell took its name, was Lord of the Isles about 1250. Their stepping stone to the Irish coast was Rathlin, which belonged to them in the days of Robert Bruce, whom Angus Og Macdonnell sheltered there in 1306. This Angus made a further step into Ireland, for he married an O'Kane and took for her dowry seven score men of all the names in O'Kane's country, that he might settle them on his lands in Cantire. Another marriage alliance of great moment was contracted by a later Macdonnell with Marjory Bisset, daughter of a Norman family, who originally settled in Scotland. But the Bissets being in trouble for slaying the Earl of Galloway, fled across to the Antrim coast, and there seized and held an estate in the Southern Glens, which came with Marjory to her husband. But the foundation of the Macdonnell power in Antrim dates from Alexander or Alastar Macdonnell, who about 1500 occupied a position on the north of Ballycastle Bay, and built there his stronghold of Duneynie. Under it lay Port Brittas, where there was easy landing for his galleys when they ran across from his lordship in Cantire. The Lordship of the Isles was now by law a thing of the past, but the Macdonnells were insubordinate vassals of the Scottish crown; and as their foothold on the Scotch coast grew less secure — and indeed from 1500 they were practically outlawed in Scotland — so they strengthened themselves on the Antrim shore. Alastar Macdonnell had six sons. James, the eldest brother, married Lady Agnes Campbell, the daughter of the third Earl of Argyll, thus for a moment reconciling two bitterly hostile houses. Moreover, though it was now treason to bear the title, he was elected Lord of the Isles. His lands in Antrim centred round Glenarm, which had come to Clandonnell as the heritage of Marjory Bisset. His brothers set themselves to extend their power northward into the Route, which was then defined as what lay between the Bush and the Bann on the shore, and between the Bann and the Glens inland. Colla Macdonnell, third of the brothers, built Kenbane Castle, whose ruins may still be seen about two miles west of Ballycastle. But he did better than that. The lords of the Route were the MacQuillins, a Norman family settled in Ireland : whether the name represents Mac Hugolin or Mac Llewellyn is disputed, but up to the days of Shane O'Neill it was recognised that the MacQuillin (it is commonly Anglicised McWilliam) was an "Englishman." MacQuillin was naturally at war with the O'Kane, for their lands marched at the Bann : and Colla brought his army of redshanks to help MacQuillin, and was victorious. Whether by MacQuillin's gratitude, or, as is more likely,

by his own imperious claim for bonachta — free quarters for his soldiery — he and his men wintered in Dunluce, and he married Eveleen MacQuillin. But little peace came of the alliance, and there were pitched battles between the clans. The final issue began to be fought out at Ballycastle, and was finished on the second day at Slieve-an-Aura, up in Glen Shesk. The MacQuillins were totally defeated, and James Macdonnell made Colla Lord of the Route and Constable of Dunluce. Colla died in 1558, and was succeeded by the most famous of these Macdonnell fighters, Sorley Boy Macdonnell.

Sorley is, Anglicised, Charles, but in reality it is an old Gaelic name, and was borne by Sorley's ancestor Somhairle or Somerled, who defended his lands in Argyll so strongly against the Danes in the eighth century. But Sorley Boy in Irish state papers is Carolus Flavus — yellow-haired Charles — and there is no want of mention of him. He was born in 1505 and lived till 1590 — a warrior till well past eighty. When Sorley became Lord of the Route in 1558, there were hard days for the Macdonnells. The English from 1530 onwards had become anxious to drive out these swarms of Scotch-Irish who poured in year by year; and in Ulster itself there was the redoubtable Shane O'Neill determined to be lord paramount in the north. In 1563 Shane made peace with Elizabeth and turned on the Clandonnell. In 1564 he defeated them in a skirmish at Coleraine, and in 1565 utterly routed them at Ballycastle and took both Sorley and James, head of the clan. Marching northward, he came to Dunluce, which baffled him; but holding Sorley, he held the key of its gates, and swore to starve the chief if he were not given admission. So on that day Dunluce was surrendered. James Macdonnell died in prison and Sorley became head of the Irish branch of the clan. In 1567 he was released from captivity by the bloody death of Shane O'Neill, who, being defeated by O'Donnell and hemmed in, turned to the Scots for help but was hacked to pieces at Cushendun. His death left the Macdonnells directly face to face with the English. Nevertheless there were not open hostilities at once. Elizabeth recognised Sorley as Lord of the Route and sent him a patent for his estates. But Sorley, receiving the parchment in Dunluce, swore that what had been won by the sword should never be kept by the sheepskin, and burnt the document before his retainers. In 1571 Walter, Earl of Essex, set out to colonise Ulster, and by way of a lesson in civilisation invited the O'Neill chieftains to a banquet, and treacherously slaughtered them. What measure he dealt to Sorley Boy's women and children in Rathlin you shall read elsewhere, but the Macdonnell chief was no more to be cowed by this butchery than on the day when they showed him his son's head on the gate of Dublin castle. "My son," he retorted, "has many heads." In 1584 Sir John Perrot marched into Ulster, and brought cannon against Dunluce that shook it sadly till it was forced to surrender. Sorley was not taken in it, and in the next year he re-captured it by treachery; but the triumphant Tudor bastard struck fear into him, and the old chief, now eighty years old, came to Dublin and there made his allegiance duly to Queen Elizabeth's portrait, going on his knees to kiss the embroidered "pantofle" of her Majesty's royal foot. He died in 1590 at his castle of Duneynie, and was buried among his kin at Bonamargy Abbey, in Ballycastle. His son, Sir James Macdonnell, succeeded him as Constable of Dunluce, but died in 1601; Sir Randal, another son of Sorley's, fortified Dunluce in defiance of orders, and joined O'Neill and Red Hugh in their rebellion; but after the defeat at Kinsale, seeing the game was up, he made timely profession of loyalty and was taken into favour by James, who granted him formally all the land from the Cutts of Coleraine to the Curran of Larne. Macdonnell remained staunch and was rewarded in 1620 with the earldom of Antrim. He died at Dunluce in 1639. His son, the second earl, had for mother Tyrone's daughter, and so was an object of suspicion, though he lived at Charles I's court and married Buckingham's widow. In 1641 came the rebellion, and a Macdonnell — the Earl's cousin — was prominent among the rebel leaders. Antrim seems to have wavered between his loyalty and a natural feeling for those who were fighting to recover the lands from which they or their fathers had been ejected. But he relieved the garrison of Coleraine and gave a hospitable welcome to General Munro in Dunluce. That officer accepted the hospitality, then seized his host and imprisoned him on suspicion in Carrickfergus. Antrim escaped, and appealed to the King; returned and was again taken by Munro, but again escaped and joined Owen Roe O'Neill, and fought strenuously for the King. Under the Commonwealth he was deprived of his estates, but like the other " innocent Papists " received an allotment in Connaught, whither the Celts, under Cromwell's policy, were being driven as if into a pen. Under the Restoration he obtained, after much difficulty, restitution of his own. But Dunluce by this time had fallen into useless ruins, and the Earl built Ballymagarry House near it as a residence. Earlier than that the castle had begun to crumble, for in 1639, when Antrim's wife, the Marchioness of Buckingham, was entertaining a great party, an outlying piece of the wall overhanging the landward mouth of the cave fell, carrying eight servants in its ruins. It was probably after this that the buildings on the near side of the chasm were erected.

Thus Dunluce has been only a picturesque accessory of the Macdonnell possessions since the Commonwealth, and not a place of strength. The later history of the family may be briefly sketched. The third Earl, like his father, was unable to take a decided part when the troubles came in 1689 : marching to the relief of Derry, he was shut out by its defenders and suffered forfeiture, but regained his estates after much petitioning. The fourth Earl in 1715 was likewise suspected of Jacobite leanings, and threatened with forfeiture. With the death of the sixth Earl in 1791 the male heirs became extinct, and the present holders of the title trace their descent through the female side. The family seat is at Glenarm, which came to the Macdonnells in the inheritance of Marjory Bisset.

I borrow a description of Dunluce Castle, as it is at present, from Mr. Cooke's Handbook.

" It is built on a projecting rock, separated from the mainland by a deep chasm about twenty feet wide, which is bridged over by a single arch about two feet broad, the only approach to the castle . . . Its exact date is not known, but it was erected by the McQuillins, probably early in the 16th century. A small enclosed courtyard is first reached, and at the lower end is a square tower, the barbican, in which is the main entrance door. From this a strong wall about seventy feet long runs along the edge of the cliff to McQuillin's Tower, circular, the walls of which are eight feet thick and contain a small staircase reaching to the summit. About twenty yards north is Queen Meave's Tower, and the connection between them has given way. At the northern extremity are the remains of the kitchen which fell, overhanging the mouth of the cave."

The castle has been made by Mr. Frank Mathew the scene of a very picturesque romance of Elizabethan times — Spanish Wine — in which, however, he invents passages communicating from above with the sea way into the cave which never have existed — probably because it is only of an odd time that boats dare enter that perilous passage.

Two other things of interest should be noted about Dunluce. The wreck of the Gerona at Port-na-Spania has been already recounted. From the wreck Sorley Boy recovered three brass guns, which were promptly claimed by Government. But Sorley refused resolutely to give them up — it must have been nearly his last act — and in 1597, when his son Randal fortified Dunluce it was on this ordnance that he largely relied. Also in 1584, when Sir John Perrot took the place, he carried away among the spoil "Holy Columbkille's cross," a relic which he sent to Burghley as being " a god of great veneration to Sorley Boy and all Ulster," though of little price for its jewels — which probably were only rock-crystals. What became of the cross no one knows ; it may some day be unearthed in some old house.

The bridge at Dunluce has really no great terrors ; it is fairly wide and the drop is not big. But it is a convenient test of your fitness to go over Carrick-a-rede, for if you feel the least nervousness at Dunluce, the wider a berth you give to Carrick-a-rede the better. The last thing to be done is either by boat or land to visit the cave, and indeed it is well worth while to do both. On the landward side of the round cliff on which stands the castle, the cave begins in a great hole like the burrow of some gigantic badger; you go down a dusty and stony path into it, and at the bottom, the salt smell of ocean gathered up in this funnel strikes you suddenly. The cave is a long tunnel not above ten yards across, and narrowing towards the exit a hundred yards away. As you stand by the water's edge — or near it, for this is a thing to be done with discretion, waves being capricious, incalculable things — looking back you see the meeting of two lights, the landward, which comes in pinkish over the stones, and the colder light reflected in from off the sea face. Overhead is a strangely regular roof with a strong resemblance to the groining that one sees in Jacobean work : and on each side springs the arch upon which rock and castle rest, with its marvellous architecture of buttresses. It is indeed a scene that might inspire a master builder.

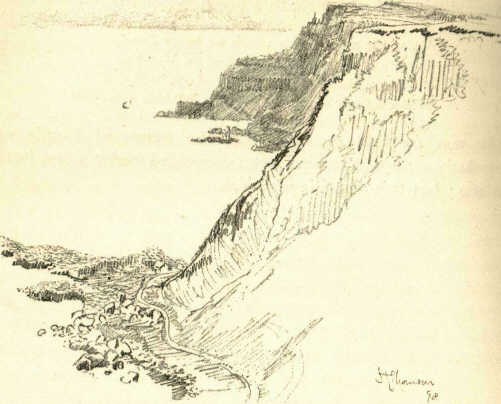

The Giant's Chimney Tops

Leaving Dunluce and getting back on to the road, you proceed for about three-quarters of a mile round the shoulder of a hill, then you open the valley of the Bush river, lying between you and Runkerry Point. On the other side of Runkerry is the Causeway. Your simplest plan is of course to follow the main road past Bushmills (where is the generating station of the electric railway), altogether a fairly level run of four miles. But this road takes you inland by a considerable detour, and there is a much prettier way by the sea, which I recommend if the tide happens to be low. Just where you round the hill a steepish road runs to the left to the little village of Port Ballintrae, a coastguard station and watering place. Ride through the town keeping close to the sea, and the road will take you to the end of a new terrace : beyond that you have to contend with nature. Lift your machine over a stile and you are on a hillside of short grassy turf with a foot-track well marked across it; this you can ride for the most part, and admire on the far side of the bay Lord Macnaghten's huge house, Runkerry Castle, standing bare and unprotected on the seaward slope. But it must not engage your whole attention or you may break the back of your machine. After about a quarter of a mile on the grass you come to another stile, and beyond it is the river Bush, flowing out into the sandy bay. About a hundred yards up to your right is a footbridge over the quiet, but pretty river, which winds sluggishly through sand-hills. I regret to say that in this river salmon are generally caught with the worm. Having got to the far side, wheel your machine along the river bank to the beach, and at low tide you will get a mile or more of fine hard sand to ride over. At the far side is a cart track, which you must lead over, and it will take you up to the road near the Causeway station and hotels. That was the plan which I had laid out for myself, but, the tide being in, I was reduced to riding my machine through the sand-hills, and it is a practice that I cannot recommend. But, under favourable conditions, it is a sporting way of doing the journey, and should be tried by every lover of leisurely short cuts.

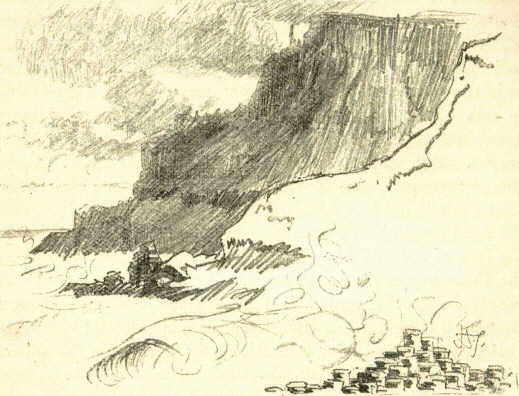

At the Causeway you will find two monstrous, ugly hotels, which, being on the landward slope, do not affect the scenery; and you had best put up at one of these if you have come from Coleraine and seen Dunluce. The Causeway should be seen by boat and by land also ; but especially by boat. A guide is inevitable, and he is also necessary to keep at arm's length the people who want to sell things. The guides are licensed, and have a printed tariff of charges : for a matter of three shillings you can get the most amazing deal of patter. For my own part, I decline to compete with their eloquence. You will have to hear a minute description of the Causeway, so why read one? Even geological theories you can get from them much better than from me. All I have to say is, that if one had discovered the Causeway somewhere in the South Pacific or in the neighbourhood of Iceland, one would have something to talk of for the rest of one's life : but as it is, everybody knows photographs of the place, and it is just like the photographs. But, when all is said, it is a very queer freak. From the picturesque point of view the best things are the caves, long tunnels not less beautiful than that under Dunluce, and the great amphitheatre bay, with the basalt columns showing in the face of the cliff like organ pipes. But for picturesqueness the Causeway cannot compare with Dunluce, with its view of the White Rocks, and it is tourist-ridden with a vengeance. Besides, a company has enclosed it with a railing, and makes visitors pay sixpence for admission — an innovation started on Easter Monday of this year, which every good Irishman resents.

If you are staying at the hotel, you should by all means walk round the cliffs which fringe the amphitheatre. Passing Seagull Island you come upon what is called Port-na-Spania (Spaniards' Bay), where the Gerona under Don Alonzo de Leyva, was lost, as I have narrated in a note on the Armada. The guides will tell you that this vessel ran in and fired at a castellated projection of the rock called The Chimney — this basalt takes semblance of architecture in the most surprising way — mistaking it for Dunluce Castle. The Spaniards may have fired guns as signals for a pilot or for relief, but they certainly would have no intention of attacking any fort — their one purpose being to get away.

Pleaskin Head, the highest of these points, attains 400 feet, and from it you have the view of the Donegal coast line to the west and the Scotch to the east. Mr. Cooke, in Murray, says it is the finest thing in the North of Ireland. I cannot agree with him, but it is a fine view.

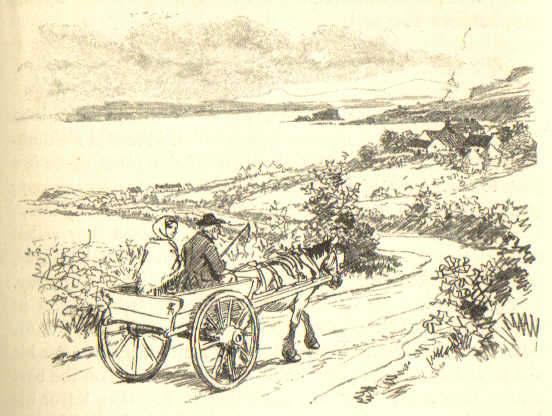

Ballycastle with Knocklayde Mountain.

CHAPTER XVII

Ballycastle from Golf Links

Your next stage from the Causeway should be Ballycastle — thirteen miles — easily done before lunch, - even if you take Carrick-a-rede on the way. About three miles after you start, the road will take you close to the ruins of Dunseverick Castle, of whose association with the Macdonnell history I have already spoken.

Four miles beyond Dunseverick you reach the village of Ballintoy, where you will see notices posted telling you to " stop here for Carrick-a-rede." Also dirty little boys will rush at you and offer to be your guides. If you like you can trust your machine to one of them and tell him to meet you at the top of the hill, and you can then strike down to the shore and walk along the cliffs until you come to the famous Swinging Bridge, which you cannot miss. But it is a considerable round, and, what is more important, the infant population of Ballintoy fills me with no confidence : they would, in my judgment, be capable of experimenting on the machine. My advice is that you should laboriously shove your cycle up the appalling hill which rises for nearly half-a-mile out of the village, until you come to a cluster of decent-looking farmhouses on the left. Here you can get a boy to go down with you to the bridge, and leave your machine in charge of one of the cottagers, who will also be glad to sell you milk or get you tea, if you desire it, while you go down the steep hill to this very curious contrivance. To your left is a small bay with white cliffs, and in it a small island — Sheep Island it is called. Carrick-a-rede itself is a gigantic rock, separated from the mainland by a deep channel sixty feet wide. Carrick-a-rede means the Rock in the Track. The salmon, with their usual tendency to follow certain tracks in the sea, come right in here along shore so that there is a chance to net them, and the nets and boats are kept on the island rock from which, at certain times of the tide, the net is shot out. There is no sort of harbour anywhere convenient, and the boats have to be hoisted on to the rock by a crane fixed on a platform of rock on the sheltered south-east side, about twenty feet above the water. During the net-fishing season, from March to October, fishermen have to go back and forwards to this island, and a bridge has been constructed of cables, from the edge of the cliff on the landward side, at a height of about eighty feet. Two cables are made fast to iron rings riveted in the rock. These are lashed together by transverse ropes and on the transverse ropes a boarding of two planks wide is laid. A single rope fixed to rings a little higher in the rock serves for a handrail, but is really more to give confidence than support. The bridge curves sharply with the weight on it, so that you go down a slope and up one again, and if there is any wind the whole thing swings sideways as well as springing under the feet. It can, of course, be crossed with perfect safety by any one who has a good head, and the natives carry sheep over it when they want to take them on or off the island; but a nervous person will find it gives disagreeable sensations and the prospect of recrossing it is not always reassuring. It is a good test to cross the Dunluce entrance first; if you have any qualms about that, Carrick-a-rede is a very good place to stay away from.

The view from the island is fine. Eastward is the line of cliffs ending in Kenbane Head : north-east the long profile of Rathlin Island — or Rachray as the natives call it — blocks the horizon. The road from the hill above Carrick-a-rede is an easy four miles to Ballycastle. To your left, though you must make a special excursion to see it, is Kenbane — the White Head — where is a great white chalk rock projecting into the sea; and behind this seaward protection Colla Macdonnell built himself a castle whose ruins are still there. Inland of it rises a cliff only to be descended by a precipitous path. Colla died in 1558 to the great joy of the English, but after his time the castle played no great part in history.

At Ballycastle you leave the Route and reach the Glens, and a prettier preface to them you could not wish for than this clean little town standing at the mouth of a pleasant stream — but, like all the streams in the Glens, of little account for fishing — with plenty of wooding about it. Inland, Knocklayd rises to 1,600 feet at the head of Glen Shesk, whence the river flows, and beyond the bay Fair Head rises, a huge mass ; the shore has the bright clean sand, so delightful a feature of this coast. Inside the beach are golf links, quite good enough for the ordinary performer and on the bay itself is a very comfortable hotel — the Marine Hotel — which I saw at Easter contending feverishly with too much prosperity. However it is presumably not always overfull, and that was the only fault that one could find with it.

The town proper stands about half-a-mile from the sea, and in it is the station of the narrow gauge Railway which runs down Glen Shesk from Ballymoney on the main line between Portrush and Belfast. A fine broad avenue with trees at either side connects the old town with the quarter down by the beach. Broad as this road is, on a fair day a bicyclist will have his work cut out to ride down it; bolting pigs, jibbing heifers, and anxiously rushing drivers, make a series of hazards that can be dealt with singly, but are very awkward to get by when they happen to concentrate themselves in one spot. It is a thrilling but an amusing experience.

The town of Ballycastle is full of histories, but it has a comparatively modern past. In 1736 a Mr. Hugh Boyd obtained from the Earl of Antrim a lease of all coal and mines from Bonamargy, where the old abbey of Ballycastle stands, to Fair Head. Within twenty years Ballycastle was an industrial centre. Mr. Boyd started work upon the coal-bed which reaches from Murlough Bay to Glen Shesk ; and, oddly enough, his workmen came upon galleries which must have been driven when England was still barbarous, and before Ireland became so. He also built iron-foundries, saltpans, breweries, tanneries, and what not, till Ballycastle became a proverb for prosperity. The Irish Parliament lent assistance, and spent over £20,000 in constructing a harbour. Then Mr Boyd died, and the whole thing fell to the ground. Dr. Hamilton, a Fellow of Trinity College, Dublin, wrote in 1786 a book on County Antrim, the first that drew attention to its scenery and curiosities. Mr. Boyd was then a few years dead : but already " the glass-works were neglected, the breweries and tanneries mismanaged, the harbour became choked up with sand, and even the collieries not wrought with such spirit." The collieries, unhappily, have gone the way of the rest. The coal is at a deep level, and the seams slant downward instead of upward ; and though, even within late years, attempts have been made to reorganise the workings at Murlough Bay — where the output could be shipped from the quarry mouth — they have always failed : and the neighbourhood remains neither enriched nor disfigured by the forces of modern industry.

The great days of Ballycastle, however, were under the Macdonnells. The Franciscan Abbey of Bonamargy was, and still is, their sanctuary and burying place. The ground of the cemetery, as Mr. Hill, their historian, puts it, " literally heaves with Clandonnell dust." Here were buried those who fell in the disastrous overthrow of Clandonnell, at the hands of Shane O'Neill in 1565 : and here, too, were buried those who died in the great fight at Slieve-an-Aura up in Glen Shesk, where the Macdonnells finally put an end to the resistance of the older lords the McQuillans. They tell a story of a clansman who went to the Countess of Antrim asking the lease of a farm. " Another Macdonnell ? " said the Countess ; " why, you must all be Macdonnells in the Low Glens." " Ay," said the peasant, " too many Macdonnells now; but not one too many on the day of Aura."

Bon-a-margy, or Bun-na-mairge, means Margyfoot (as Bun-crana means Cranagh Foot, Bundoran, Drowes Foot, and so on). The Margy has only a course of half-a-mile up to the point at which the Shesk and Carey rivers join by Dun-na-Mallaght Bridge.

But the Ballycastle shore leads one far back into memories of an older time, long before the Clandonnell came into being. Into the river Margy there often sailed four white swans that were the children of Lir, king of the Isle of Man. For Lir's wife died, and he married her sister, who looked unkindly on the children of the first wedlock, and by a magical wand changed them to four swans, doomed to live in that transformation till nine hundred years should pass over them — for three hundred of which they were to toss on the stormy Moyle—or till the sound of Christian bells should be heard in Ireland. So it was until Columbkille came, and with a holier magic released them. But however it ended, the Fate of the children of Lir is the second of Erin's Three Sorrows of Story. The third and greatest of the Sorrows of Story is the Fate of the Sons of Usnach; and it was at Carrig-Usnach, the sloping rock on the north side of Fair Head, that the three sons of Usnach landed when they returned to Eire with Deirdre, beautiful as Helen and gifted like Cassandra with unavailing prophecy. It may be worth while for those who do not know the Celtic legends to hear the story.

In the days when Conor was king of Uladh or Ulster, Conor feasted at the house of Phelim, the king's story-teller; and while they feasted word came to Phelim that his wife had borne him a daughter. Caffa, the Druid, was of the company, and he rose up and said : " Let her name be Deirdre (that is Dread), for by reason of her beauty many sorrows shall fall upon Uladh." Then the nobles were for putting her to death at once, but Conor said, " No, but I will take her and she shall be reared to be my wife." Conor put her away in a lonely castle with his own conversation-dame Lavarcam for a nurse, to watch over her. And Deirdre grew up and fulfilled the promise of her beauty ; but she was lonely for want of love and one day she saw blood spilt in the snow and a raven drinking it. " I would," she said, " I had a youth of those three colours ; his hair black as the raven, his cheek red as the bloodstain, and his skin white as the snow." Then Lavarcam said to her, " Naisi, son of Usnach, of Conor's household, is such a one." And so the dame brought the two together, for she loved Deirdre more than she feared the king, and it was agreed between them that they should fly. Naisi took with him his two brothers, Ainli and Ardan, and a company of soldiers, and they crossed the sea to Alba, where the prince of that country made them soldiers and leaders of his own. But word came to him of Deirdre's beauty, and he was for seizing her by force; but the sons of Usnach defeated him and fled with Deirdre to a sea-girt islet on Lough Etive, and there they lived happily by the chase.

Now King Conor assembled his nobles in the great Eman or Hall of Macha, that is Armagh, and there was eating and drinking, and harpers, and bards, and all men's hearts were full of content. Then Conor rose up and said to them, " Saw you ever a palace fairer and richer than this my house of Eman ?" and they said, " We saw none." Then Conor asked, " Is there nought lacking ? " and they said, " We know of nought." "Ay," said Conor, " but there is a want that vexes you, the want of the three sons of Usnach, that are exiles from Eire, and have won for themselves a province in Alba." Then they all shouted applause, "for," said they, " these three alone should suffice to guard Ulster." Then Conor asked, " Who will go now to Lough Etive to bring me back the sons of Usnach ? for Naisi is under vow not to return westwards unless it be under the warranty of one of these three — Conall Carnach, or Fergus, son of Roy, or Cuchullan — and now I will know which of the three best loves me."

And with that he took Conall Carnach into a place apart, and asked him "What would he do if the sons of Usnach should come over under his warranty and then be slain ? " " It is not one man's life should pay for that," said Conall, " but upon every Ultonian that had art or part therein I would inflict death." " I perceive," said Conor, " you are no friend of mine." Then he took Cuchullan and questioned him in like manner. " I pledge you my word," said Cuchullan, " that if this should come to pass I would slay every man of Ulster that my hands could reach." " You are no friend of mine," said Conor, and he drew Fergus apart and questioned him. " There is no man in Ulster should injure them," said Fergus, " but his life should pay for it, save only yourself." "It is you shall go for them," said Conor ; " and set you forth in the morning and bring them to the mansion of Barach, on the shore of Moyle, and pledge me your word that you send the sons of Usnach to Eman, so soon as ever they shall arrive, be it night or day with them."

Then Conor went to Barach, and asked had he a feast ready for his king. " Ay," said Barach, "but I could not bring it to Eman." " Offer it to Fergus, then," said the king, when he returns from Alba ; for he is under gesa never to refuse a feast."

But Fergus set out for Alba, taking with him no troop but his two sons, Ulan the Fair and Buine the Red Fierce One, and Callan his shield-bearer. And when he came into the harbour of Lough Etive he sent forth a loud cry.

Naisi and Deirdre were playing at the chess, and Conor's chessboard was between them that they carried off in their flight. Naisi lifted up his face and said, " I hear the call of a man of Erin." " It was not the call of a man of Erin," said Deirdre, " but the call of a man of Alba." Then Fergus shouted again and again. Naisi said, " It is the cry of a man of Erin." "Truly it is not," said Deirdre; "let us play on." Then Fergus shouted a third time, and the sons of Usnach knew his voice, and Naisi said to Ardan, " Go out and meet Fergus, the son of Roy." Then Deirdre said to him, " I knew well it was the voice of a man of Erin." " Why did you hide it, then, my queen ? " said Naisi. " I dreamt a dream last night that three birds came to us from Eman of Macha having three sups of honey in their beaks ; and they went away taking three sups of our blood with them." " And how read you the vision ? " said Naisi. " It is this," said Deirdre. " Fergus comes to me with a message of peace from Conor; for honey is not sweeter than a message of peace from a false heart." "Let that be," said Naisi. " Fergus stays long in the port."

Meanwhile Fergus and his sons were greeting Ardan, and they came to where Naisi and Deirdre and Ainli were. So the exiles asked for tales of Erin. " The best tales I have," said Fergus, " are that Conor has sent us hither to bring you back under my warranty." " Let us not go," said Deirdre, " for our lordship in Alba is greater than the sway of Conor in Erin." "Birthright is first," said Fergus, " for ill it goes with a man, although he be great and prosperous, if he does not see daily his native earth." "It is a true word," said Naisi, " for dearer to me is Eire than Alba, though I should win more gain in Alba than in Erin." But it was against the will of Deirdre that they departed, though Fergus pledged them his word, and said, " If all the men of Eire were against you, little it would avail them while we and you stood by one another."True it is," said Naisi, " and we will go with you into Eire."

So they sailed away over the sea, and Deirdre sang this song as she lost the sight of Alba. " My love to thee, O Land in the East, and 'tis ill for me to leave thee, for delightful are thy coves and havens, thy kind soft flowery fields, thy pleasant green-sided hills, and little was our need for departing."

Then in her song she went over the glens of their lordship, naming them all, Glen Lay, Glen Marsin, Glen Archeen, Glen Etty, and Glen da Roe, and calling to mind how here they hunted the stag, here they fished, here they slept with the swaying fern for pillows, and here the cuckoo called to them. And "Never," she sang, "would I quit Alba were it not that Naisi sailed thence in his ship."

They landed under Fairhead at Corrig Usnach, and thence they went to the mansion of Barach. Then Barach welcomed them, and he said, "For you, Fergus, I have a feast ready, and you must not leave it." Then Fergus grew red in anger, and said, " Ill done it is of you, Barach, to ask me to a feast, for I am bound under stern vows to speed the children of Usnach on to Eman of Macha." Then Barach reminded him of his gesa, and Fergus appealed to the sons of Usnach for counsel. "You have your choice," said Deirdre ; "will you forsake the feast or forsake the sons of Usnach ? " "I will not forsake them," he said, " for I will send my two sons, Ulan the Fair and Buine the Red Fierce One with them to Eman of Macha." Then Naisi answered in wrath : " We find no fault with the escort; it is not any other person that has ever defended us, but we ourselves." Then the company went on, leaving Fergus sad and sorrowful. But Deirdre counselled them to go to Rathlin, and abide there till Fergus should have partaken of his feast; " for so," she said, " shall Fergus keep his word, and your lives shall be lengthened." But the sons of Fergus said she had but scant confidence in them; and Naisi refused her counsel. They rested on the mountain of Fuad, and Deirdre dreamed a dream, and she tarried behind them. Naisi came back to seek her, and asked why she tarried. " A sleep was upon me," said Deirdre, "and I saw a dream in it." " What was the dream ? " said Naisi. " I saw Ulan the Fair, and his head was struck off him, and I saw Buine the Red, and his head was on his shoulders : and the help of Buine the Red was not with you, and the help of Ulan the Fair was with you."

So they journeyed on till they came to the hill of Ardmacha, and Deirdre said to Naisi, " I see a cloud in the sky, and it is a cloud of blood ; and I would give you counsel, sons of Usnach." "What counsel ? " said Naisi. " Go to Dundalgan where Cuchullan lies, and be under the safeguard of Cuchullan till Fergus end his feasting, for fear of the treachery of Conor." " There is no fear upon us, and we will not practise that counsel," said Naisi.

As they drew near to Eman of Macha, Deirdre spoke a last warning. " I have a sign for you, O sons of Usnach," she said, " if Conor designs to commit treachery on you or no." " What sign is that ?" said Naisi. " If Conor summon you into the hall where are the nobles of Ulster with him, he has no mind to treachery ; but if you be sent to the mansion of the Red Branch, there is treachery."