From: Picturesque Ireland; a Literary and Artistic Delineation of Its Scenery, Antiquities, Buildings, Abbeys Etc. - Savage, John (editor) 1884

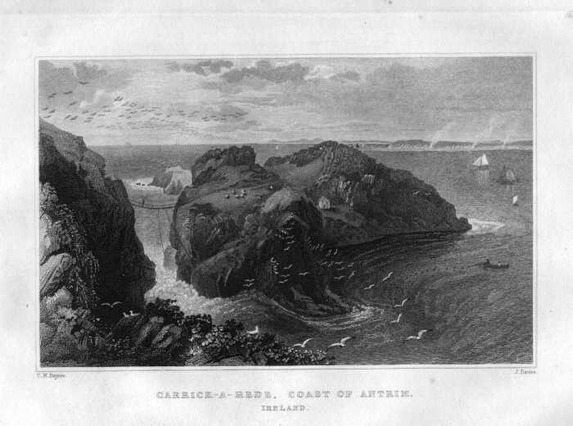

Carrick-a-Rede, so called from being a "rock in the road," which intercepts the course of the salmon along the coast - is another highly striking promontory or islet on this romantic shore, which derives additional interest from being connected with the mainland by a flying rope-bridge flung across an appalling chasm. The island is over three hundred feet high, and contains about two and a half acres; and the frightful bridge, made for the accommodation of fishermen in summer-time, is constructed in a simple manner. Two strong cables are extended across the gulf by an expert climber and fastened firmly into iron rings mortised into the rock. Between and upon these ropes boards a foot in breadth are laid crosswise in succession on which other boards are fastened lengthways by cross-cords, and thus the aerial pathway is formed, which, though broad enough to bear a man's foot with tolerable convenience, does not by any means hide from view the pointed rocks and raging sea beneath. This light and airy contrivance, swaying and undulating in a space sixty feet wide, and over a chasm ninety feet deep, presents an appearance of danger which undeniably affects even persons of strong nerve. The greatest caution is necessary in using the hand-rope placed on one side as a guide. The slightest inadvertence in placing too much weight on it would precipitate the passenger headlong into the sea, or what is worse, on to the rocks. It is, as Hamilton suggests, a beautiful bridge in scenery, but a frightful one in real life. The people in the habit of using it, however, pass and repass with apparent ease; and even the fishers' wives and sons carry burdens across with evident contempt of danger. Still, from a boat in the water, and gazing upward, it is painful to see people crossing the bridge, and distressing to anticipate the imminent danger to which they are incessantly exposed in their struggle for existence. It may be asked, says a writer, why the fishermen do not spare themselves the trouble of throwing across this very dangerous bridge, and approach the island by water? and the answer is given that it is perfectly impracticable, owing to the extreme perpendicularity of the basaltic cliffs on every side, except in one small bay, which is only accessible at particular periods. The residents in the little cottage on the island comprise the clerk and the fishermen, who remain only during the summer months. "This salmon fishery, and indeed all those along the northern coast, are very productive. The fishermen are paid, and all the expenses of fishing defrayed, by proportionate allowances of salmon." There is a beautiful and remarkable cave of unsupported basaltic columns, thirty feet high - the bases of which have been washed away or otherwise removed - in the cliffs near the island. The shores around Carrick-a-Rede are exceedingly picturesque. and the surface which alternates with the high cliffs and rocks very beautiful, romantic and fertile. One of the finest views afforded on the whole coast of Antrim is obtained from a little eminence above the path leading from the old Ballycastle road down to "the Rock in the Road." Proceeding west through the hamlet of Ballintoy, and by the bay of the same name, we reach, at a distance of some four miles, the remarkable rock and ruins of Dunseverick. The rock is isolated, of perpendicular form, one hundred and twenty feet in height, and about half an acre in area on the top. The Castle is a solitary remnant of a ruin like that at Kenbane and other cliff castles on this coast, and the whole presents a strikingly romantic and suggestive aspect. "Immense masses of the rock have been hewn away, evidently for the purpose of rendering the castle as inaccessible as possible. An enormous basaltic rock, south of the entrance, also appears to have been cut in a pyramidal form, and flattened on the top, perhaps as a station for a warder, or for the use of some engine of defense." The locality is invested with peculiar interest to the historical student from the fact that it perpetuates the name of Sovarkie, one of the earliest Milesian kings of Ireland, who with his brother Kermna, jointly ruled the king-dom nearly twelve hundred years before the Christian era. They were the first Ulster kings of Ireland; and the portion north of a line from Drogheda to Limerick was governed by Sovarkie, who built a fortress-palace named Dun Sovarkie. The neighborhood naturally took the name of the fort, as Fort Washington and Fort Hamilton give names to places in the neighborhood of New York; but it is doubtful if the area of the rock, as seen at present, would have accommodated the dimensions of Dun Sovarkie. A portion of the fortress - a look-out - may have been on the rock, as it seems to be agreed by antiquarians "that a fortress existed here long before the introduction of Christianity." It was a chosen place for a stronghold, and the ruin, represented in the illustration, the walls of which were eleven feet thick, is the remnant of one of the McQuillans' castles - subsequently occupied by the O'Cahans - and dates to the twelfth century. The tourist now has his choice of two routes to the Causeway - one by a walk along the headlands, the other by the road to Bushmills, and thence to the Causeway. The author of Tours in Ulster is justified in his selection of the former, as being one of the most varied, most singular, and interesting walks to be found in any country. Every step is replete with novelty. The thousand little objects, that can scarcely be named - grotesque fragments of rocks, little tiny amphitheaters scooped out of the cliffs - these, combined with the striking and majestic features of the more celebrated points of view keep the mind in a state of pleasing excitement, and produce impressions, such, perhaps, as no other class of scenery would impart. The same writer recommends the tourist to suitably prepare himself for this walk by procuring No.3 of the Ordnance Map of Antrim for handy and frequent reference (Tours in Ulster etc. By J. B. Doyle. Illustrated, 1854) to which we would add that his own book will be a useful pocket companion to the map. After Dunseverick we meet the rock of sorcery, Ben an Danaan, and next a fine cascade where the stream from Feagh Hill plunges over the cliffs into Port Moon. The leading features of this coast, as Hamilton remarks, are the two great promontories of Bengore and Fair Head, which are eight miles distant from each other: both formed on a great and extensive scale, both abrupt toward the sea, abundantly exposed to observation, and each in its kind exhibiting noble arrangements of the different species of columnar basalts. Fair Head has already been described. Bengore is about seven miles from Ballycastle. In reaching it from Dunseverick we pass some nine " ports," each from an eighth to a quarter of a mile in extent, with its particular name, and some with striking rocks - such as the Hen and her Chickens, the Stack, the Four Sisters, which the guides will point out. Bengore, viewed at a distance on sea, presents a headland pro-file running out a considerable dis-tance from the coast into the ocean. Strictly speaking, however, it is made up of several capes, the tout ensemble of which forms what the seamen call the Headland of Bengore. These capes are composed of a variety of different ranges of pillars, and a great number of strata ; which, from the abruptness of the coast, are extremely conspicuous, and form an unrivalled pile of natural architecture, in which all the neat regularity and elegance of art is united to the wild magnificence of nature. In every ocean view from Fair Head to Bengore, and indeed from points south-east of the former and far west of the latter, the Island of Rathlin (also called Ragherry, Rachlin, Rachrin) is a prominent object, varying, of course, in size and position, from the point of view. Its nearest points to the mainland are about three miles from Fair Head, and five and a half from Ballycastle. Its form is a rude resemblance to a low legged boot, the toe of which points to Ballycastle collieries, the top, Bull Point, to the Atlantic Ocean, and the heel, where Bruce's Castle is situated, to the Scottish coast of Cantyre, which is nearly fifteen miles distant. From the top to the heel is five miles, and from the heel to the toe four. Its breadth varies from half a mile to a mile and a quarter. On the inside of the bend is Church Bay. The highest point on the northwestern part - North Kenramer - is 447 feet above the sea level ; and the cliffs all around the northern shores, from Bruce's Castle to the recess of Church Bay, very precipitous, averaging 300 feet. This small island, surrounded as it is by a wild and turbulent sea, fortified by barriers of inhospitable rock, and containing little or nothing in itself to pro-voke the rage of either avarice or ambition, might, suggests Dr. Drummond, be supposed to have escaped the desolating scourge of war. But if its almost inaccessible retirement recommended it as a home for peace and religion, the latter also awakened piratical cupidity ; while its commanding position and natural defenses suggested its use both as a warlike rendezvous, and as a refuge for the heroic unfortunate. Hence history records many pages of blood and rapine on the little theater of this island. It has felt the fury and rapacity of Danish, English and Hebridian arms. The monastery established by St. Columba, with all its shrines, was ravaged and destroyed in 790; and again in 973 by the Danes, who, on their second descent, killed the abbot. The memory of a dreadful massacre by the Highland Scotch Campbells is still preserved; and a place called Sloc Na Calleach ("slaughter of the old women ") perpetuates a tradition of the destruction of all the aged women of the island, by precipitation over the rocks. The barbarian author of the atrocity was named MacNalreavy. Hamilton remarks that in his time the memory of this deed was so strongly impressed on the inhabitants that no person of the name of Campbell was allowed to settle on the island. After the disgraceful execution of William Wallace, by Edward I., and the disruption of Scottish claims and rights, Robert Bruce found a refuge here when forced to leave his native country. He was pursued, how-ever, and the remains of the fortress, on the northern angle of the island, celebrated for the defense which the hero made in it, is still known as Bruce's Castle. The antiquity of this building is nearly six centuries; indeed, "it may be consider-ably older, as the time which Bruce spent in Rathlin was scarce sufficient for the purpose of erecting it." Here it was that the Bruce received the lesson in perseverance from watching the labors of a spider, which, after several failures. succeeded in securely fastening its web to a beam, that led him to the glorious field of Bannockburn. Since then it has been held unlucky and ungrateful, says Scott, for one of the name of Bruce to kill a spider. The English invaded Rathlin unsuccess-fully in 1551 but seven years later the Lord-Deputy Sussex drove out the Scots with great carnage. Rathlin - the Ricina of Ptolemy - has long been an object of study as well as of curiosity, on account of the similarity of its shores to those on the coast of Antrim, from which, it is supposed, it has been severed by some awful convulsion. Geologists agree that the structure of the island and the adjacent mainland are identical, and Hamilton was of opinion that this island, standing between the coasts of Antrim and Scotland, may be the surviving fragment of a large tract of country, which at some period of time has been buried in the deep, and may have formerly united Staffa and the Giant's Causeway. The island is principally occupied by those basaltic beds which are classified by Dr. Berger under the heads: tabular basalt, columnar basalt green-stone, graystone, porphyry, bole or red ochre, wacke, amygdaloidal wacke, and wood-coal; and imbedded in them are granular olivine augite, calcareous spar, steatite, zeolite, iron pyrites, glassy feldspar, and chalcedony. Doon Point, on the eastern coast, is regarded as a beautiful and remarkably curious development of the process of basaltic formations, presenting, as it does, a combination of perpendicular, horizontal and bending pillars. It is thought "more worthy of observation than the Causeway, and better calculated to explain the phenomenon of the basaltic crystallizations." Its base resembles a mole composed of erect columns like those of the Giant's Causeway; over the extremity of this mass, others appear in a bending form, as if they had slid over in a state of softness, capable of accommodating themselves to the course of their descent, and thus assuming the figure of various curves in consequence of the action of gravity; over all, several pillars are disposed in a horizontal position, such as would accord with an hypothesis of their having just reached the brink of the ascent, where they were suddenly arrested and became rigid, lying along with their extremities pointing out toward the sea. (See Hamilton, p.128; Drummond, pp. 168-171) The channel between the main and the island is very turbulent, the eastern opening being insufficient for the press of waters from the Atlantic, which consequently returns in a counter-current tide westward for thirty miles, while the true tide is running east. The channel is called the Valley of the Sea (Sleuck na Massa), and also Brecan's Caldron, or hollow (Corrie-Brecain), in consequence of the loss here of Brecain-son of Nial of the Nine Hostages - and his fleet of fifty Curraghs. Nothing can be grander than the Atlantic rolling with the tide, but no sooner does the ebb oppose itself to this mighty mass of waters, than the wild-est confusion occurs, the waves foaming and tossing in a fearful manner. The rushing of the waters from the Scottish and Irish shores at each other is vividly described in Cormac's Glossary. They are sucked down as if into a gaping caldron. "The waters are again thrown up, so that their belching, roaring. and thundering are heard amidst the clouds, and they boil like to a caldron upon a fire." In the Lord of the Isles, founded on adventures of Bruce after he left Rathlin, Scott alludes to the "roar" of " Corryvreken's whirlpool rude."

Carrick-a-Rede, so called from being a "rock in the road," which intercepts the course of the salmon along the coast - is another highly striking promontory or islet on this romantic shore, which derives additional interest from being connected with the mainland by a flying rope-bridge flung across an appalling chasm. The island is over three hundred feet high, and contains about two and a half acres; and the frightful bridge, made for the accommodation of fishermen in summer-time, is constructed in a simple manner. Two strong cables are extended across the gulf by an expert climber and fastened firmly into iron rings mortised into the rock. Between and upon these ropes boards a foot in breadth are laid crosswise in succession on which other boards are fastened lengthways by cross-cords, and thus the aerial pathway is formed, which, though broad enough to bear a man's foot with tolerable convenience, does not by any means hide from view the pointed rocks and raging sea beneath. This light and airy contrivance, swaying and undulating in a space sixty feet wide, and over a chasm ninety feet deep, presents an appearance of danger which undeniably affects even persons of strong nerve. The greatest caution is necessary in using the hand-rope placed on one side as a guide. The slightest inadvertence in placing too much weight on it would precipitate the passenger headlong into the sea, or what is worse, on to the rocks. It is, as Hamilton suggests, a beautiful bridge in scenery, but a frightful one in real life. The people in the habit of using it, however, pass and repass with apparent ease; and even the fishers' wives and sons carry burdens across with evident contempt of danger. Still, from a boat in the water, and gazing upward, it is painful to see people crossing the bridge, and distressing to anticipate the imminent danger to which they are incessantly exposed in their struggle for existence. It may be asked, says a writer, why the fishermen do not spare themselves the trouble of throwing across this very dangerous bridge, and approach the island by water? and the answer is given that it is perfectly impracticable, owing to the extreme perpendicularity of the basaltic cliffs on every side, except in one small bay, which is only accessible at particular periods. The residents in the little cottage on the island comprise the clerk and the fishermen, who remain only during the summer months. "This salmon fishery, and indeed all those along the northern coast, are very productive. The fishermen are paid, and all the expenses of fishing defrayed, by proportionate allowances of salmon." There is a beautiful and remarkable cave of unsupported basaltic columns, thirty feet high - the bases of which have been washed away or otherwise removed - in the cliffs near the island. The shores around Carrick-a-Rede are exceedingly picturesque. and the surface which alternates with the high cliffs and rocks very beautiful, romantic and fertile. One of the finest views afforded on the whole coast of Antrim is obtained from a little eminence above the path leading from the old Ballycastle road down to "the Rock in the Road." Proceeding west through the hamlet of Ballintoy, and by the bay of the same name, we reach, at a distance of some four miles, the remarkable rock and ruins of Dunseverick. The rock is isolated, of perpendicular form, one hundred and twenty feet in height, and about half an acre in area on the top. The Castle is a solitary remnant of a ruin like that at Kenbane and other cliff castles on this coast, and the whole presents a strikingly romantic and suggestive aspect. "Immense masses of the rock have been hewn away, evidently for the purpose of rendering the castle as inaccessible as possible. An enormous basaltic rock, south of the entrance, also appears to have been cut in a pyramidal form, and flattened on the top, perhaps as a station for a warder, or for the use of some engine of defense." The locality is invested with peculiar interest to the historical student from the fact that it perpetuates the name of Sovarkie, one of the earliest Milesian kings of Ireland, who with his brother Kermna, jointly ruled the king-dom nearly twelve hundred years before the Christian era. They were the first Ulster kings of Ireland; and the portion north of a line from Drogheda to Limerick was governed by Sovarkie, who built a fortress-palace named Dun Sovarkie. The neighborhood naturally took the name of the fort, as Fort Washington and Fort Hamilton give names to places in the neighborhood of New York; but it is doubtful if the area of the rock, as seen at present, would have accommodated the dimensions of Dun Sovarkie. A portion of the fortress - a look-out - may have been on the rock, as it seems to be agreed by antiquarians "that a fortress existed here long before the introduction of Christianity." It was a chosen place for a stronghold, and the ruin, represented in the illustration, the walls of which were eleven feet thick, is the remnant of one of the McQuillans' castles - subsequently occupied by the O'Cahans - and dates to the twelfth century. The tourist now has his choice of two routes to the Causeway - one by a walk along the headlands, the other by the road to Bushmills, and thence to the Causeway. The author of Tours in Ulster is justified in his selection of the former, as being one of the most varied, most singular, and interesting walks to be found in any country. Every step is replete with novelty. The thousand little objects, that can scarcely be named - grotesque fragments of rocks, little tiny amphitheaters scooped out of the cliffs - these, combined with the striking and majestic features of the more celebrated points of view keep the mind in a state of pleasing excitement, and produce impressions, such, perhaps, as no other class of scenery would impart. The same writer recommends the tourist to suitably prepare himself for this walk by procuring No.3 of the Ordnance Map of Antrim for handy and frequent reference (Tours in Ulster etc. By J. B. Doyle. Illustrated, 1854) to which we would add that his own book will be a useful pocket companion to the map. After Dunseverick we meet the rock of sorcery, Ben an Danaan, and next a fine cascade where the stream from Feagh Hill plunges over the cliffs into Port Moon. The leading features of this coast, as Hamilton remarks, are the two great promontories of Bengore and Fair Head, which are eight miles distant from each other: both formed on a great and extensive scale, both abrupt toward the sea, abundantly exposed to observation, and each in its kind exhibiting noble arrangements of the different species of columnar basalts. Fair Head has already been described. Bengore is about seven miles from Ballycastle. In reaching it from Dunseverick we pass some nine " ports," each from an eighth to a quarter of a mile in extent, with its particular name, and some with striking rocks - such as the Hen and her Chickens, the Stack, the Four Sisters, which the guides will point out. Bengore, viewed at a distance on sea, presents a headland pro-file running out a considerable dis-tance from the coast into the ocean. Strictly speaking, however, it is made up of several capes, the tout ensemble of which forms what the seamen call the Headland of Bengore. These capes are composed of a variety of different ranges of pillars, and a great number of strata ; which, from the abruptness of the coast, are extremely conspicuous, and form an unrivalled pile of natural architecture, in which all the neat regularity and elegance of art is united to the wild magnificence of nature. In every ocean view from Fair Head to Bengore, and indeed from points south-east of the former and far west of the latter, the Island of Rathlin (also called Ragherry, Rachlin, Rachrin) is a prominent object, varying, of course, in size and position, from the point of view. Its nearest points to the mainland are about three miles from Fair Head, and five and a half from Ballycastle. Its form is a rude resemblance to a low legged boot, the toe of which points to Ballycastle collieries, the top, Bull Point, to the Atlantic Ocean, and the heel, where Bruce's Castle is situated, to the Scottish coast of Cantyre, which is nearly fifteen miles distant. From the top to the heel is five miles, and from the heel to the toe four. Its breadth varies from half a mile to a mile and a quarter. On the inside of the bend is Church Bay. The highest point on the northwestern part - North Kenramer - is 447 feet above the sea level ; and the cliffs all around the northern shores, from Bruce's Castle to the recess of Church Bay, very precipitous, averaging 300 feet. This small island, surrounded as it is by a wild and turbulent sea, fortified by barriers of inhospitable rock, and containing little or nothing in itself to pro-voke the rage of either avarice or ambition, might, suggests Dr. Drummond, be supposed to have escaped the desolating scourge of war. But if its almost inaccessible retirement recommended it as a home for peace and religion, the latter also awakened piratical cupidity ; while its commanding position and natural defenses suggested its use both as a warlike rendezvous, and as a refuge for the heroic unfortunate. Hence history records many pages of blood and rapine on the little theater of this island. It has felt the fury and rapacity of Danish, English and Hebridian arms. The monastery established by St. Columba, with all its shrines, was ravaged and destroyed in 790; and again in 973 by the Danes, who, on their second descent, killed the abbot. The memory of a dreadful massacre by the Highland Scotch Campbells is still preserved; and a place called Sloc Na Calleach ("slaughter of the old women ") perpetuates a tradition of the destruction of all the aged women of the island, by precipitation over the rocks. The barbarian author of the atrocity was named MacNalreavy. Hamilton remarks that in his time the memory of this deed was so strongly impressed on the inhabitants that no person of the name of Campbell was allowed to settle on the island. After the disgraceful execution of William Wallace, by Edward I., and the disruption of Scottish claims and rights, Robert Bruce found a refuge here when forced to leave his native country. He was pursued, how-ever, and the remains of the fortress, on the northern angle of the island, celebrated for the defense which the hero made in it, is still known as Bruce's Castle. The antiquity of this building is nearly six centuries; indeed, "it may be consider-ably older, as the time which Bruce spent in Rathlin was scarce sufficient for the purpose of erecting it." Here it was that the Bruce received the lesson in perseverance from watching the labors of a spider, which, after several failures. succeeded in securely fastening its web to a beam, that led him to the glorious field of Bannockburn. Since then it has been held unlucky and ungrateful, says Scott, for one of the name of Bruce to kill a spider. The English invaded Rathlin unsuccess-fully in 1551 but seven years later the Lord-Deputy Sussex drove out the Scots with great carnage. Rathlin - the Ricina of Ptolemy - has long been an object of study as well as of curiosity, on account of the similarity of its shores to those on the coast of Antrim, from which, it is supposed, it has been severed by some awful convulsion. Geologists agree that the structure of the island and the adjacent mainland are identical, and Hamilton was of opinion that this island, standing between the coasts of Antrim and Scotland, may be the surviving fragment of a large tract of country, which at some period of time has been buried in the deep, and may have formerly united Staffa and the Giant's Causeway. The island is principally occupied by those basaltic beds which are classified by Dr. Berger under the heads: tabular basalt, columnar basalt green-stone, graystone, porphyry, bole or red ochre, wacke, amygdaloidal wacke, and wood-coal; and imbedded in them are granular olivine augite, calcareous spar, steatite, zeolite, iron pyrites, glassy feldspar, and chalcedony. Doon Point, on the eastern coast, is regarded as a beautiful and remarkably curious development of the process of basaltic formations, presenting, as it does, a combination of perpendicular, horizontal and bending pillars. It is thought "more worthy of observation than the Causeway, and better calculated to explain the phenomenon of the basaltic crystallizations." Its base resembles a mole composed of erect columns like those of the Giant's Causeway; over the extremity of this mass, others appear in a bending form, as if they had slid over in a state of softness, capable of accommodating themselves to the course of their descent, and thus assuming the figure of various curves in consequence of the action of gravity; over all, several pillars are disposed in a horizontal position, such as would accord with an hypothesis of their having just reached the brink of the ascent, where they were suddenly arrested and became rigid, lying along with their extremities pointing out toward the sea. (See Hamilton, p.128; Drummond, pp. 168-171) The channel between the main and the island is very turbulent, the eastern opening being insufficient for the press of waters from the Atlantic, which consequently returns in a counter-current tide westward for thirty miles, while the true tide is running east. The channel is called the Valley of the Sea (Sleuck na Massa), and also Brecan's Caldron, or hollow (Corrie-Brecain), in consequence of the loss here of Brecain-son of Nial of the Nine Hostages - and his fleet of fifty Curraghs. Nothing can be grander than the Atlantic rolling with the tide, but no sooner does the ebb oppose itself to this mighty mass of waters, than the wild-est confusion occurs, the waves foaming and tossing in a fearful manner. The rushing of the waters from the Scottish and Irish shores at each other is vividly described in Cormac's Glossary. They are sucked down as if into a gaping caldron. "The waters are again thrown up, so that their belching, roaring. and thundering are heard amidst the clouds, and they boil like to a caldron upon a fire." In the Lord of the Isles, founded on adventures of Bruce after he left Rathlin, Scott alludes to the "roar" of " Corryvreken's whirlpool rude."