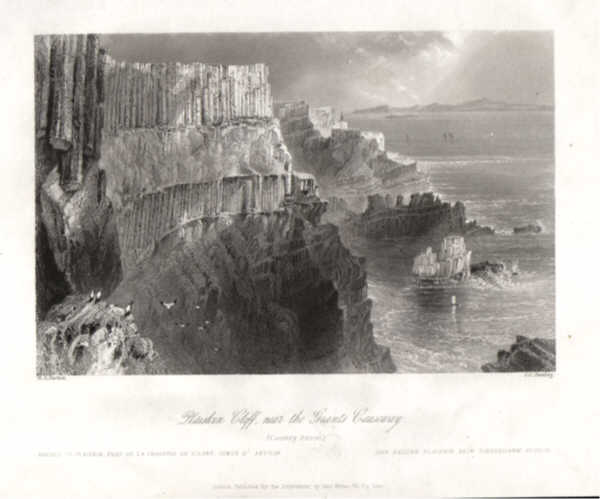

Plaiskin Cliff

Proceeding eastward toward the promontory of Bangore, the traveller comes to the Pleaskin Cliff, commonly said to be the most beautiful promontory in the world. The natural basaltic rock here lies immediately under the surface. About twelve feet from the summit, the rock begins to assume a columnar tendency, and is formed into ranges of rudely columnar basalt, in a vertical position, exhibiting the appearance of a grand gallery, whose columns measure sixty feet in height. This basaltic colonnade rests upon a bed of coarse, black, irregular rock, sixty feet thick, abounding in air-holes. Below this coarse stratum is a second range of pillars, forty-five feet high, more accurately columnar, and nearly as accurately formed as the Causeway itself. The cliff appears as though it had been painted for effect in various shades of green, vermillion, red-ochre, grey lichens, &C.J its general form so beautiful, its storied pillars, tier over tier, so architecturally graceful-its curious and varied stratifications supporting the columnar ranges; here the dark brown amorphous basalt, there the red-ochre, and below that again the slender but distinct lines of wood-coal; all the edges of its different stratifications tastefully varied, by the hand of nature, with grasses, ferns, and rock-plants-in the various strata of which it is composed, sublimity and beauty have been blended together in the most extraordinary manner.

Proceeding eastward toward the promontory of Bangore, the traveller comes to the Pleaskin Cliff, commonly said to be the most beautiful promontory in the world. The natural basaltic rock here lies immediately under the surface. About twelve feet from the summit, the rock begins to assume a columnar tendency, and is formed into ranges of rudely columnar basalt, in a vertical position, exhibiting the appearance of a grand gallery, whose columns measure sixty feet in height. This basaltic colonnade rests upon a bed of coarse, black, irregular rock, sixty feet thick, abounding in air-holes. Below this coarse stratum is a second range of pillars, forty-five feet high, more accurately columnar, and nearly as accurately formed as the Causeway itself. The cliff appears as though it had been painted for effect in various shades of green, vermillion, red-ochre, grey lichens, &C.J its general form so beautiful, its storied pillars, tier over tier, so architecturally graceful-its curious and varied stratifications supporting the columnar ranges; here the dark brown amorphous basalt, there the red-ochre, and below that again the slender but distinct lines of wood-coal; all the edges of its different stratifications tastefully varied, by the hand of nature, with grasses, ferns, and rock-plants-in the various strata of which it is composed, sublimity and beauty have been blended together in the most extraordinary manner.

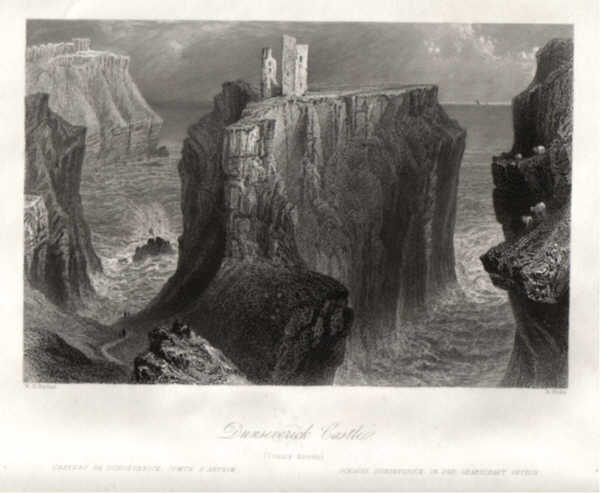

Dunseverick Castle

About three miles east of the Giant's Causeway we came in sight of a detached and lofty rock, elevating its head near the centre of a small bay, and crowned with the ruins of the Castle Of Dunseverick. It is a lonely remnant of a structure, and though traces of the outworks are visible, the "keep" is the only part that is still erect, and this too, from its appearance, will soon be as prostrate us the rest. Immense masses of the rock have been hewn away, evidently for the purpose of rendering the castle as inaccessible as possible. An enormous basaltic rock, south of the entrance, also appears to have been cut of a pyramidal form, and flattened on the top, perhaps as a station for a warder, or for the purpose of placing upon it some engine of defence. That the insulated rock on which the castle is placed should, from its peculiar strength, have been selected by the early settlers in Ireland as a proper situation for one of their strongholds, is not to be wondered at, but of that original fortress M'Skimmin remarks, there are no remains. The present ruin, though of great strength, the walls being eleven feet in thickness, is evidently of an age not anterior to the English invasion, and most probably erected by the M'Quillans, but the annals of the time are silent as to the period of its re-edification.

About three miles east of the Giant's Causeway we came in sight of a detached and lofty rock, elevating its head near the centre of a small bay, and crowned with the ruins of the Castle Of Dunseverick. It is a lonely remnant of a structure, and though traces of the outworks are visible, the "keep" is the only part that is still erect, and this too, from its appearance, will soon be as prostrate us the rest. Immense masses of the rock have been hewn away, evidently for the purpose of rendering the castle as inaccessible as possible. An enormous basaltic rock, south of the entrance, also appears to have been cut of a pyramidal form, and flattened on the top, perhaps as a station for a warder, or for the purpose of placing upon it some engine of defence. That the insulated rock on which the castle is placed should, from its peculiar strength, have been selected by the early settlers in Ireland as a proper situation for one of their strongholds, is not to be wondered at, but of that original fortress M'Skimmin remarks, there are no remains. The present ruin, though of great strength, the walls being eleven feet in thickness, is evidently of an age not anterior to the English invasion, and most probably erected by the M'Quillans, but the annals of the time are silent as to the period of its re-edification.

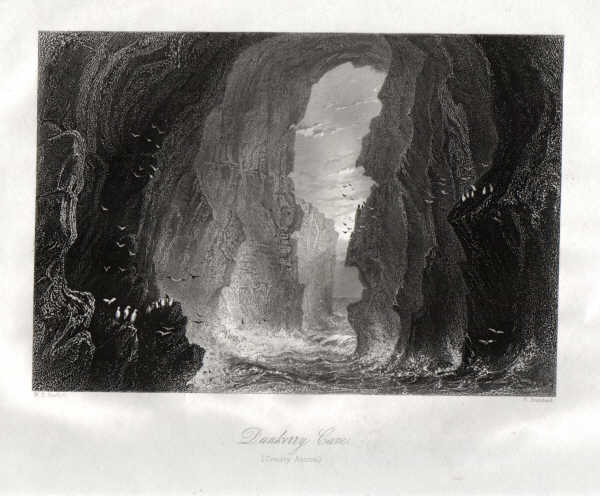

Dunkerry Cave

West of the Causeway lie one or two very remarkable caves, one of them accessible both by land and sea, the other, the Cave Of Dunkerry, accessible by water only. The entrance to the latter assumes the appearance of a pointed arch, and is remarkably regular. The boatmen are singularly expert in entering these caves. They bring the boat's head right in front, and, watching the roll of the wave, quickly ship their oars, and float in majestically upon the smooth heave of the sea. The depth of Dunkerry Cave has not been ascertained, for the extremity is so constructed as to render the management of a boat there impracticable and dangerous. Besides, from the greasy character of the sides of the cave, the hand cannot be serviceable in forwarding or retarding the boat. Along the sides is a bordering of marine plants, above the surface of the water, of considerable breadth. The roof and sides are clad over with green confervce, which give a very rich and beautiful effect, and not the least curious circumstance connected with a visit to this subterraneous apartment is the motion of the water within. It has been frequently observed that the swell of the sea upon this coast is at all times heavy; and as each successive wave rolls into the cave, the surface rises so slowly and awfully that a nervous person would be apprehensive of a ceaseless increase in the elevation of the waters until they reached the summit of the cave. Of this, however, there is not the most distant cause of apprehension, the roof being sixty feet above high-water mark. The roaring of the waves in the interior is distinctly heard; but no probable conclusion can be arrived at from this as to the depth. It is said, too, that the inhabitants of some cottages, a mile removed from the shore, have their slumbers frequently interrupted in the winter's nights by the subterranean sounds of Dunkerry Cave. The entrance is very striking and grand, being twenty-six feet in breadth, and enclosed between two natural walls of dark basalt, and the visitor enjoys a much more perfect view of the natural architecture at the entrance, by sitting in the prow with his face to the stern as the boat returns.

West of the Causeway lie one or two very remarkable caves, one of them accessible both by land and sea, the other, the Cave Of Dunkerry, accessible by water only. The entrance to the latter assumes the appearance of a pointed arch, and is remarkably regular. The boatmen are singularly expert in entering these caves. They bring the boat's head right in front, and, watching the roll of the wave, quickly ship their oars, and float in majestically upon the smooth heave of the sea. The depth of Dunkerry Cave has not been ascertained, for the extremity is so constructed as to render the management of a boat there impracticable and dangerous. Besides, from the greasy character of the sides of the cave, the hand cannot be serviceable in forwarding or retarding the boat. Along the sides is a bordering of marine plants, above the surface of the water, of considerable breadth. The roof and sides are clad over with green confervce, which give a very rich and beautiful effect, and not the least curious circumstance connected with a visit to this subterraneous apartment is the motion of the water within. It has been frequently observed that the swell of the sea upon this coast is at all times heavy; and as each successive wave rolls into the cave, the surface rises so slowly and awfully that a nervous person would be apprehensive of a ceaseless increase in the elevation of the waters until they reached the summit of the cave. Of this, however, there is not the most distant cause of apprehension, the roof being sixty feet above high-water mark. The roaring of the waves in the interior is distinctly heard; but no probable conclusion can be arrived at from this as to the depth. It is said, too, that the inhabitants of some cottages, a mile removed from the shore, have their slumbers frequently interrupted in the winter's nights by the subterranean sounds of Dunkerry Cave. The entrance is very striking and grand, being twenty-six feet in breadth, and enclosed between two natural walls of dark basalt, and the visitor enjoys a much more perfect view of the natural architecture at the entrance, by sitting in the prow with his face to the stern as the boat returns.

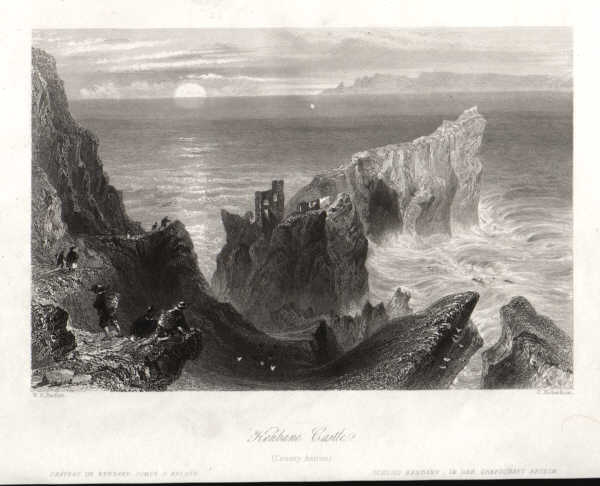

Kenbane Castle

About two miles north-west of the town of Ballycastle, on a narrow peninsula, composed of white limestone, which projects its perpendicular front into the sea, are the ruins of the ancient Castle Of Kenbaan, or the White Promontory-a name derived from that of the precipitous cliff on which it stands. At present little remains of this building except a part of the massy walls of the tower or keep, which, from its bold and romantic situation, adds not a little to the beauty of the scenery of this romantic coast. During summer, it is often frequented by parties, and is the scene of many a festive collation; where, instead of the grim warder pacing at its gate, are seen inside the portal the " fairest of the fair."

About two miles north-west of the town of Ballycastle, on a narrow peninsula, composed of white limestone, which projects its perpendicular front into the sea, are the ruins of the ancient Castle Of Kenbaan, or the White Promontory-a name derived from that of the precipitous cliff on which it stands. At present little remains of this building except a part of the massy walls of the tower or keep, which, from its bold and romantic situation, adds not a little to the beauty of the scenery of this romantic coast. During summer, it is often frequented by parties, and is the scene of many a festive collation; where, instead of the grim warder pacing at its gate, are seen inside the portal the " fairest of the fair."

|

BIOGRAPHY OF ARTIST: William Henry Bartlett, (b London, 26 March 1809; died at sea off Malta, 13 Sept 1854) was an English draughtsman, active also in the Near East, Continental Europe and North America. He was a prolific artist and an intrepid traveller. His work became widely known through numerous engravings after his drawings published in his own and other writers' topographical books. His primary concern was to extract the picturesque aspects of a place and by means of established pictorial conventions to render 'lively impressions of actual sights', as he wrote in the preface to The Nile Boat (London, 1849). His several views of Ireland were done in the latter half of 1939, and as Nathaniel Parker Willis stated, "Bartlett could select his point of view so as to bring prominently into his sketch, the castle or the cathedral, which history or antiquity had allowed". The interest in these engravings today is as much for the quality of the rendering and presentation of the architecture of the period as it is for the representation of the landscape.

|